Playing with Lego bricks is a fond childhood memory for many and the brand is still popular with children around the world today. But only six years ago, Lego very nearly became nothing more than a memory. Founded in 1932 by carpenter Ole Kirk Christiansen, the first toys were made from wood and it was nearly 20 years later that the company began making its iconic plastic building blocks.

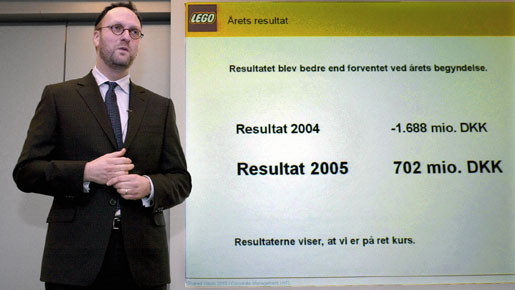

Lego went from strength to strength, becoming a household name across the world. But then, in 1998, the business began to falter. For the first time in the history of the company, Lego posted a loss of €26m and by 2003 it was clear that the company was simply haemorrhaging money, posting a record loss €126m. Smelling blood, private equity companies began to circle and at one point it appeared that the company would be swallowed up by US toy giant, Mattel. Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, grandson of the founder, ploughed a significant amount of his own money into the company, but realised that more drastic measures needed to be taken. Kristansen did something that had never been done before in the history of Lego – he handed over the reins to someone from outside the family.

Enter Jørgen Vig Knudstorp. Something of an unusual choice, Knudstorp was only 36 when he took over from Kristiansen as CEO and President, and had only been with the company for three years. As it turned out, this wildcard played by Kristiansen was exactly what Lego needed. Although Knudstorp had entered the firm at directorate level, he had been there for much less time than others at the same level, many of whom had more than ten years of experience. But what he could offer that others couldn’t was his knowledge from his time at McKinsey & Company and an outsider’s perspective. He put emphasis on a subject that had been largely taboo before – making money.

During the 1990s, the company had diversified into clothing, theme parks, jewellery, video games and baby products, while abandoning traditional favourites such as Duplo and Lego City, in an attempt to modernise the brand. “We had diversified too much and too quickly, going into areas in which we had no experience,” says Knudtsorp. Upon taking over, he analysed the company and asked ‘why does Lego Group exist?’ The answer, ‘to offer our core products, whose unique design helps children learn systematic, creative problem solving – a crucial twenty-first century skill,’ is what led the turnaround.

Knudstorp has compared Lego to books; people have declared at various points within the past that films, TV and the digital revolution will put paid to books. However, as is evident, this has not been the case. “Just as children still want to read books and not just watch movies, they still want to have that physical Lego building experience that cannot be replaced by digital play,” he told the Editor of Monocle, Tyler Brûlé. With these things in mind, Knudstorp set about stripping out items such as Legoland that were a distraction, rather than an asset, and brought back the familiar lines that had been abandoned. Knudstorp, aware of his relative inexperience within the company, took on as his mantra the Danish saying of ‘managing at eye-level’ by making himself familiar to all teams.

However, this streamlining wasn’t painless by any means – although by 2006 the company was making a profit exceeding any made during the late 90s and early 2000s, the decision was taken to outsource nearly all production to Flextronics. Production was moved to the Czech Republic and Mexico. Nearly half of Lego’s global workforce was made redundant in the process.

Many see this as Knudstorp’s biggest error in the Lego turnaround. In 2006, he made the statement that the decision to outsource was “the last major step in our process of restructuring of the Group’s supply chain, which has been implemented since 2004 with the purpose of cutting total production costs by 1bn Kroner (€1.3m).” Only two years later, production was brought back in house. Why? To reduce production costs. This experience is a good example for anyone of how cost-cutting measures can sometimes end up being anything but that. The return to in house production had an added PR benefit for Lego, when in 2009 toys manufactured by rivals in China were found to contain lead paint, leading to massive product recalls. Lego was catapulted from a brand trusted for reasons of nostalgia to one trusted because of its concern for safety when others seemed to have been reckless when choosing their suppliers.

So the saviour of Lego turned out not to be as miraculously faultless as it first appeared, but he is still the man responsible for saving a brand loved by so many people from oblivion. Under his watch, Lego has gone from making a €259m net loss in 2004 to a €181.5m net profit in 2008. Certainly not bad for someone who has only been in the job for six years, even more remarkable when you consider he’s only 41.