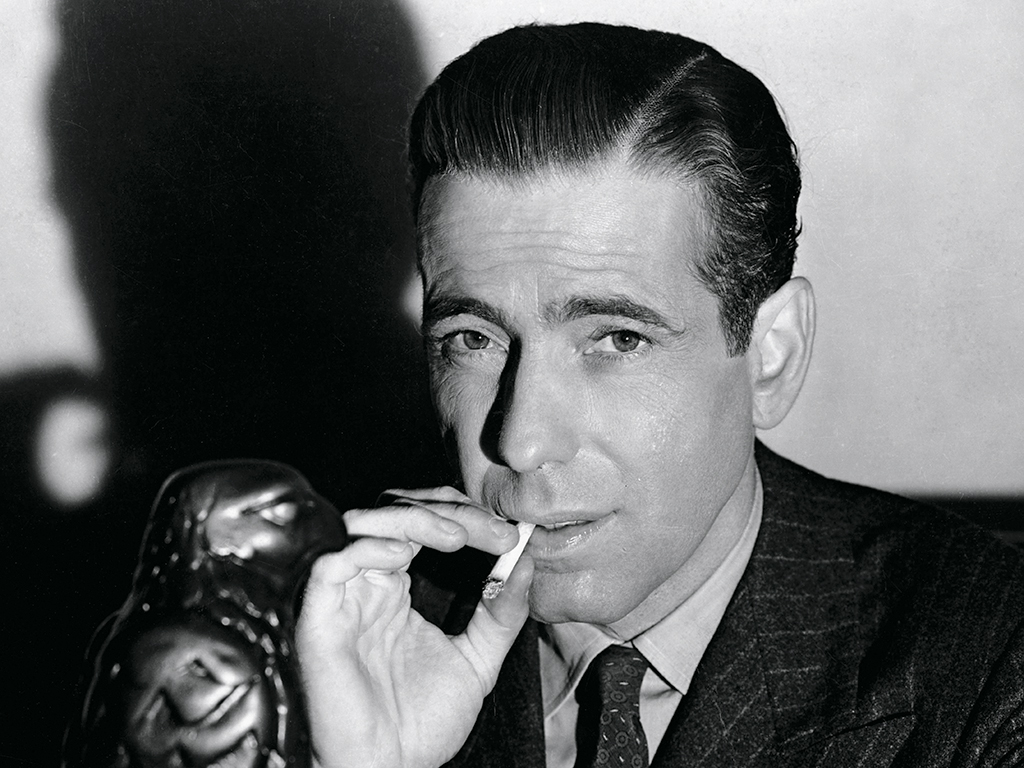

Humphrey Bogart sits at a table with his brow slightly furrowed and holds a cigarette between his forefinger and thumb up to his lips. His eyes smoulder as he gazes directly into the camera. It’s a classic shot of Bogey; his left hand clasped around a dark Maltese falcon figure, and his shadow harsh against the grey background. It is a promotional shot from the 1941 classic The Maltese Falcon, still considered one of the best pictures of the film noir genre ever made.

[I]ts roots lie in the widespread social tensions that permeated American society between the end of the Great Depression and the Cold War

Since the 1940s, film noir pictures have captured Hollywood’s imagination. Over the past 10 years, there has even been a resurgence of the genre with the release of neo-noir pictures such as Sin City and Drive. It is not hard to pinpoint exactly what makes film noir so appealing to audiences old and new. Dramatic storylines depicting criminal underbellies and cynical anti-heroes have often felt like the perfect antidote to the slew of saccharine romantic comedies that have been a Hollywood mainstay since the inception of the industry.

Visually, film noir pictures are extremely well-crafted affairs, with dramatic lighting, and bleak cityscapes, often featuring extended shots of a deserted street or lonely figure. The aesthetic is both appealing and powerful. Shots of lone men in trench coats and hats, standing in the rain, as smoke rises slowly from their lips have become commonplace in our collective conscious. As have the archetypal figures that inhabit the underworld of film noir – the dangerous dames, bent cops, unwilling heroes and drunken losers who are thrown together amid a series of unfortunate events.

Such striking imagery is the focus of a new collection from Taschen, which captures this dark mood in a film-by-film book based on both the film noir and neo-noir genres. Film Noir. 100 All-Time Favorites, edited by Paul Duncan and Jürgen Müller, features photography from early American, German and French influencers of the genre, as well as works from the likes of Alfred Hitchcock and Roman Polanski, and follows the evolution of the genre with recent cult favourites.

Style and substance

Though the genre is now pervasive and a cornerstone of the Hollywood movie industry, its roots lie in the widespread social tensions that permeated American society between the end of the Great Depression and the Cold War.

Economic uncertainty and the imminent threat of further violence permeated the inter-war era in North America, and film noir borrows heavily from German expressionist cinematography to address those concerns visually. Perhaps more than with any other genre since the silent era, style and aesthetics are as vital as dialogue for the telling of the story.

But even if the genre was borne out of a very specific set of environmental circumstances, the universal appeal of film noir has endured because of the appealing themes these films share. Film noir first appeared an aesthetic manifestation of the fear and uncertainty of the 30s and 40s, but the dark, brooding cynicism that permeates these pictures are facets of the human condition that have always existed in one form or another. The enduring appeal of noir as a genre lies in how the characters subvert the traditional motifs that have become so common in Hollywood. Heroes are flawed, women are dangerous and nothing is what it seems.

Though as a genre noir has been widely parodied over the decades, it has survived the test of time more than any other genre or style. In fact, in the six decades since The Maltese Falcon, films of this genre have constantly been awarded top accolades, and have been commercial and critical successes. Often we think of classic films from the 1940s, such as Double Indemnity and The Big Sleep ,when we think of film noir, but later gangster classics such as Chinatown and even Pulp Fiction should not be left out of the debate.

Politically motivated

Though some elements of the original noir genre have faded away or become out-dated, such as the famed protagonist narration, a lot of the imagery has been carried forward. The archetypal underdog or antihero is still the driving force of any noir, and the central character’s role as an outsider remains the overriding theme.

Noir films also remain steeped with political ideology, even if the central theme is not political. The roots of this are historical; in the 1940s, Hollywood was flooded with European filmmakers and writers who were fleeing the war and generally bringing leftist political ideologies stateside. These were men and women who had once made up the intellectual left in Europe, fleeing fascism and cultural annihilation – the films they made in the US were clearly steeped in these feelings of otherness on the surface, but political undertones were never far behind. These European expatriates – Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder and Otto Preminger – came armed with two decades of experience of expressionist cinema, with European noir already an established genre in itself. They brought with them narratives of deep angst, a proclivity to indulge in nihilism and a deep preoccupation with aesthetics.

Neo-noir is no different. Although narratives have gotten more complex the themes remain the same. Films such Drive and The Dark Knight may appear unconventional as noirs but upon closer inspection all the signs are there. In Nicholas Winding Refn’s Drive, the protagonist in a disenfranchised young male who comes under the spell of his attractive neighbour and whose life slowly starts to collapse as he finds himself embroiled in a web of crime and violence. With Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, not only is Bruce Wayne the archetypal noir hero – an outsider with a solid moral compass who is forced to do bad things for the greater good – but Gotham is also the physical embodiment of the corrupt underbelly setting of the typical noir.

Dark arts

Though at first glance the archetypal noir formula may seem a bit tired and dated, neo-noir has managed to reinvigorate the genre without making it into a pastiche of itself. Though films such as Sin City rely heavily on the traditional noir storytelling techniques – the off-screen narration, the vocabulary and the character build – it pushes the envelope so far aesthetically that the entire thing is lifted to new artistic highs. Sin City used the typical high-contrast black and white style of original noir films and elevates it to cartoonish new levels to achieve a film so visually striking that it single-handedly breathed new life into the genre.

The language of noir may have changed, but the themes remain the same – borne of the basic human instinct to question our environment. The world might not run awash with private eyes, femme fatales, gritty gangsters and doe-eyed dames, but it is still swamped with treachery, corruption, lust and madness. And as long as it is, we will continue to make art from the shadows.

For further information visit taschen.com