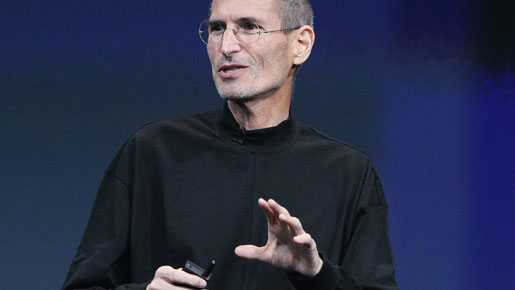

As any seasoned mariner worth his salt will tell you, if you want to understand the character of a ship, look no further than its captain. The same would appear to apply to commercial enterprises if you take Apple Computer Inc, and its co-founder, Chairman and CEO, Steve Jobs as an example. During its early years when Jobs was largely driving product development, Apple was showing the world, along with its much larger competitors, what the personal computer could deliver in terms of both product features and shareholder value. Through the hiatus of Jobs’ nine year expulsion, the company fell into a slough of uninspiring, overpriced products and poor financial performance. Then, when an older and managerially wiser Steve was brought back into the fold, the company was pared down, re-focused and inspired once again to delight both consumers and investors with its slick innovation.

Yet despite the impressive returns being generated, shareholders remain nervous of having such an iconic and mercurial character at the helm, and perhaps with good reason. The vast body of biographical and analytical literature on Steve Jobs builds a complex profile of a man who bullied everyone around him to get his own way; someone who deceived his business partner, lost lucrative business alliances out of sheer petulance and expropriated the creative inventions of countless people. Behind the public face of Jobs’ success, the story is one of turbulence, discord, failure and deceit. But it is also a story of luck, brilliance, creativity and growing maturity that struck gold in the chaotic beginnings of the computer and consumer electronics industry.

A question of style

Jobs grew up in California during the 1960s. It was a time when all the rules of society were being challenged, and a place where deconstruction was revered. By most published accounts, Jobs was a restless youngster with a keen interest in electronics, and a willful streak that was bent on getting his own way. He is reported to have bullied his parents into moving house so he would not have to attend a school he didn’t like, chosen to attend a college that was beyond their financial means, then dropped out due to boredom, but hung around and audited classes that interested him. He did more than experiment with drugs, and spent several months wandering barefoot around India seeking spiritual enlightenment.

When he returned to California, he rekindled his earlier love affair with electronics, taking a job at Atari Inc. and beginning to work on his old friend Steve Wozniak, who was by all accounts a gifted, self-taught electronics engineer, to build Jobs’ vision of a better computer. The equation that was set up during that first working relationship became the hallmark of Jobs’ modus operandi; someone else’s technology, Steve’s design. Although Jobs’ name appears as co-inventor on over 100 patent applications, the weight of anecdotal evidence supports the view that he rarely, if ever, actually built a piece of hardware or wrote a line of code. What Jobs brought to the equation was an absolute obsession with design detail and user experience, which he imposed on the creative people around him through a combination of inspiration and bullying. In his own words, what Jobs did best was “finding a group of talented people and making things with them”.

The result was often a technological and market coupe that captured the imagination of an increasingly cultish following of customers. The fact that his designs were radically different from what the computer giants of the day were saying was feasible, and delivered a level of style and utility that users fell in love with, was at the heart of Apple’s early success. And it is success, more than anything else, that attracts and retains talented staff. The opportunity to be part of the development of products that actually change the world was a motivator powerful enough to secure their loyalty despite recurring stories of staff being generally underpaid in the industry, driven to exhaustion on ridiculously short deadlines and often berated and demeaned in front of their peers when they didn’t measure up to Jobs’ exacting standards. But as Leander Kahney notes in Wired Magazine, “Jobs’ employees remain devoted… because his autocracy is balanced by his famous charisma – he can make the task of designing a power supply feel like a mission from God.”

Strategic brilliance or luck?

As the company began to grow on the success of the initial Apple computers, the young Steve’s single-minded focus on achieving ‘his’ vision began to create friction. In their book iCon; Steve Jobs, the Greatest Second Act in the History of Business, Jeffrey Young and William Simon describe how, when Apple investors recruited John Scully from Pepsi-Cola to bring experience and professional management skills to the role of Apple CEO, he found himself increasingly battling with Steve for control of the company. Still in his late 20’s, Jobs believed only he could understand what the customer wanted, and therefore he should be involved in every aspect of product design, development and marketing. His propensity for micromanagement has never left him. Matters came to a head when Jobs decided that the successful line of Apple computers, then in development for a third generation release, should be scrapped in favour of a completely different machine. He latched onto the early designs of another engineer, set up a separate development area and began poaching the best talent from the rest of the business into a team that he protected within a shield of secrecy and elitism. The Macintosh was born, but the Board eventually revolted against his high-handedness and Jobs was forced out.

What ensued for the Apple computer company was nine years of poor results and management disarray. The initial Macintosh was not the resounding success that its predecessor, the Apple, had been, largely because Jobs had failed to do any market research. As a result, the visionary’s design did not include many of the hardware features that had initially drawn customers to the Apple brand – practical things like lots of memory and expansion slots, and delightful things such as a colour display. What it did have, on Jobs’ insistence, was the first graphical user interface (GUI), which awed the Apple community and has been almost universally copied.

Meanwhile, Jobs became involved in two more ventures; NeXT, a computer company he started to produce commercial workstations targeted initially at universities, and Pixar, which had developed some revolutionary hardware and software to produce computer animation. Both companies nearly failed, however, because Jobs continued to believe that the most important part of the computer experience was the hardware. His conviction that the Pixar machines, capable of handling vast amounts of data for graphical imaging work, would find a ready market within the medical community nearly led to the demise of that business. What saved it was the creative genius of its animation director, John Lassiter, who used those computers to create four blockbuster animated films in a row, triggering a buy-out by Walt Disney studios.

With NeXT, the story was similar. Jobs was pushing for a hardware design triumph that would prove that he had been the genius behind Apple’s success. With hundreds of millions of dollars from investors such as Canon and Ross Perot, he pushed through with his design ideas and built a state of the art manufacturing plant. The ‘Cube’, when it was finally released, was a flop, with the same faults that had plagued the Macintosh – an overpriced machine that lacked some of the basic features that users wanted. However, the unique object-oriented operating software that was developed to run the Cube nearly catapulted Jobs into the position of worldwide software dominance now enjoyed by Bill Gates. According to Young and Simon, IBM entered into negotiations with Jobs to ship their personal computers with the NeXT operating system. Jobs threw their initial contract document in the bin, and delayed ensuing negotiations to such an extent that when a contract was finally signed it was too late. A regime change in IBM brought an abrupt end to the relationship with NeXT and IBM started shipping its computers with Microsoft Windows instead. By the time Apple decided to buy the company in a bid to acquire that same operating system, NeXT was close to bankruptcy.

Back inside the company he co-founded, Jobs wasted no time in pushing to oust the incumbent CEO, Gil Amelio and take over. History shows that on Jobs’ watch, Apple has become stunningly successful, producing superlatively innovative products, attracting great talent and managing a tight business. Several observers have pointed out, however, that much of the cost cutting and re-focusing agenda that enabled the business to turn itself around and survive in the first few years of his stewardship had actually been put in place by Amelio.

By that time, Jobs was coming to understand that the magic embedded in his vision of beautifully designed computers lay in the software/hardware interface, and no one can deny that the steady stream of creative new products (iTunes, iPod, iPhone, iBook, iMac, iMovies) to come out of Apple since 1997 is pure Steve Jobs. Or is it? Van Baker, Research Vice President at Gartner Group believes not, and cautions against the fallacy of indulging in Jobs worship. “Everybody acts like Steve makes every decision for Apple every day,” he complains. “That’s just not true.” But part of the reason that Jobs could succeed where others failed to tame the Apple culture is because he created it. The atmosphere of secrecy and elitism that he fostered in his early days is continued today, with many developers not knowing about work on other components of their own projects within Apple. Many analysts believe this is a calculated strategy to ensure the products hit the market before competitors have any idea what is coming. What it leads to, however, is the need to provide a single point of focus to maintain coherence both inside and outside the company. That point of focus is Steve Jobs.

“Apple has pursued a deliberate strategy of making Steve Jobs into the public persona of the company,” continues Baker. “With Steve taking the limelight, it has allowed the executive team to just do their jobs on a day to day basis.” But in a company that is used to operating secretly and micro-managing its public image, what happens when that public persona becomes seriously ill?

Apple without Steve Jobs

Nik Rawlinson, Editor of MacUser, gave an abrupt and unfriendly, “No comment”, when asked what the future of Apple would look like without Steve Jobs. That kind of messianic loyalty to Jobs is common among Apple fans, but Baker points out that it is unhelpful to the future of company and its products. “What will happen to Apple if Steve Jobs’ absence becomes permanent,” he asks? “Nothing. Apple have some of the best people in the industry. Jonny Ives is world renowned on the design side; Tim Cook is a very good operations guy; Bertrand [Serlat] is excellent on software, and Phil [Schiller] is very good at marketing. They’re all very capable, and they will step up to the challenge. Apple will be missing the person that is the public persona, that is all.”

Worryingly, shareholders might take a different view of the company’s future. As Adrian Hewison, President of INO.com, an award-winning information site for financial market traders, explains. “The real key to the value of Apple is that Steve was very instrumental in pulling all the pieces together and creating really cool products,” he says. “They may have somebody else who is very good at engineering, somebody else who is very good at interface design, but the magic of Steve is that he is basically able to pull all the pieces together and make it cohesive.”

Jobs’ total focus on the consumer experience enabled Apple to build a huge business on a product range of less than 30 products – a strategy that is also seen to be both a strength and a weakness for the company. “With a small product portfolio, if you execute extremely well, as Apple does, you can be very successful,” Baker notes. “Time and again, Apple has shown itself to be capable of shooting its best selling product in order to keep its portfolio fresh. Having said that,” counters Hewison, “their product cycles are getting old. The competition is coming in with products like the Palm Pre, which looks very much like an Apple iPhone and does some things that the iPhone doesn’t do at this point in time. There is also a saturation point for all these products, which may come even earlier than it otherwise would, given that we are entering a recession.”

The combination of a downturn in the global economy with more rapid shifts in the consumer electronics market create additional watch points for Apple’s future. Is Jobs’ insistence on maintaining proprietary software to tie consumers in to Apple products still a viable strategy in a consumer world that is increasingly embracing interoperability? Are there any aspects of consumer living left to be transformed with the Apple magic, or has the run of wow-inducing innovation reached its finale? Observers of this years’ Macworld convention, the traditional unveiling of lust-inducing products like the iPod and iPhone, were disappointed to find that the only offering of substance amounted to a few tweaks on existing products.

Two other threats are looming that may cause the Board to take its eye off the ball. The first will come from disgruntled shareholders, licking their wounds from recent battering on the financial markets. The December 2008 announcement of Steve’s current medical leave of absence from his role as Chairman and CEO was sudden and, some say, not entirely open about the prognosis for his future health. “A lot of Apple stock is held by institutions,” Hewitt explains. “If the price continues to drift downwards, even if it is only following the bear markets in general, I expect to see some lawsuits against the Board. As the price erodes, the shareholders will attempt to recover their losses by claiming that because material information on Steve’s health was withheld, they were unable to make a good judgment on holding this stock.”

A second challenge is lurking in the files of the US Securities and Exchange Commission. In an almost exact replica of a transaction that took place at Pixar when Steve Jobs was CEO, Apple has been accused of backdating prices on some employee stock options. Although Jobs himself denies culpability, a new administration in the White House is encouraging a more rigorous approach to corporate governance, and that may well bring about a re-visitation of the transactions at both Pixar and Apple.

So with challenges arising from economic downturns, a small and tiring product line, and fewer opportunities to apply the famous Apple innovation, the future of the company may well depend more on custodial management than the single-minded visionary drive that characterises Steve Jobs. But perhaps Steve himself should have the last word. In an interview with Fortune’s Betsy Morris in March 2008, Jobs commented, “My job is to make the whole executive team good enough to be successors, so that’s what I try to do.

Timeline

- In January 1984, Apple Computer introduced the Macintosh, the PC that brought the mouse and the point-and-click interface to the masses.

- It was lunched with and ad entitled ‘1984’ and directed by Ridley Scott, which ran during the Super Bowl.

- The $2,549 Mac had no hard drive and the keyboard had no arrow keys, forcing users to navigate with the mouse

- In 1995, Apple settled a lawsuit by astronomer Carl Sagan. He’d objected to developers using his name as the codeword for the Power Mac 7100. Apple changed it to BHA, but Sagan still was not satisfied – he’d read news reports saying that BHA stood for ‘butt-head astronomer’.

- 1998 was the introduction of the iMac which ditched the traditional floppy disc drive for the less widely used compact disc for removable storage, the iBook was introduced in 1999 and had more that 140,000 pre-orders.

- 2006 saw the first Apple computer using an Intel chip: The MacBook Pro, some macs still use the Intel chip although the newer models prefer Nvidia processing units.

- In 2008, Apple launched the MacBook Air which it boasts is ‘the world’s thinnest notebook’.