Three years after the global financial crisis of 2008/09, world trade, as well as economic and financial activities, are once again threatened. Only this time, the menace is coming from the eurozone sovereign debt crisis. Nonetheless, deleveraging in America and Europe could still be as much of a long-term boon for east Asia as it is a short-term bane for financial markets and economies.

East Asia is sensible enough to be aware that its improved fundamentals have increased its resilience to the woes in the West, but not made it immune to them. While east Asia is expected to remain the fastest-growing region in the world, its ability to turn this crisis into an opportunity will depend on how quickly it formulates policies to meet the challenges of the changed landscape after the global crisis.

To achieve this, east Asia must first understand how the deleveraging in the US and eurozone is creating friction with certain inconsistencies in the global currency system.

Global inconsistencies

The first inconsistency is the dominance of the US dollar in the international financial sector in an increasingly multi-polar world economy. Second, the euro is the world’s second-largest reserve currency but is, unfortunately, a multiple currency peg system within the eurozone, and structurally incomplete without a fiscal union. Third, China is the world’s second-largest economy and needs to align itself toward more open capital markets and market-determined exchange rates. Fourth, the world’s major reserve currencies – the US dollar, the euro, the British pound and the Japanese yen – are all saddled with wide fiscal deficits and large public debt burdens, not helped by dysfunctional politics that render policymaking ineffective in pushing structural reforms. These G4 currencies have lost or are at risk of losing their triple-A sovereign debt ratings, with their central banks focusing more on managing the size of their balance sheets than conducting monetary policy. In turn, this has serious implications for the post-crisis international financial system that relies on them to establish risk-free benchmark yield curves.

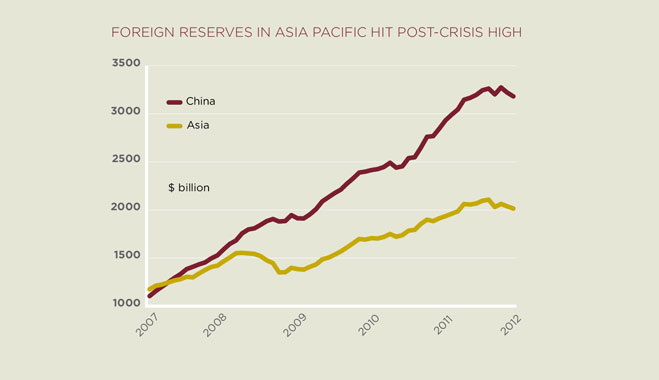

In retrospect, 2011 has been a serious wake up call for east Asia to adapt to the fundamental reshaping of the global economic and financial landscape. With the West no longer able to spend and import as freely, it is now less conducive for east Asia to preserve the real value of foreign reserves by carrying on the pre-crisis practice of accumulating and diversifying foreign reserves, especially into euros in a weak US dollar environment. In response, gold, the yuan, commodity currencies, and other triple-A rated currencies have emerged as alternatives to the G4 currencies for reserve management. Equally challenging is the global liquidity shortage as a result of deleveraging in the world’s two largest major reserve currencies. To cope with potential shortages here, some Asian countries have established and/or expanded bilateral swap arrangements with each other.

Addressing imbalance

In the view of DBS Bank, the global liquidity situation is also a symptom of global imbalances. Officially, this showed up as expanded balance sheets in the G4 central banks, and as high foreign reserves in emerging economies. Together, this did not imply material progress in improving global imbalances, which the West considers an important factor keeping the post-crisis world financial system vulnerable, and the economic recovery fragile.

The biggest imbalance remains the contentious bilateral trade deficit between the world’s two largest economies. The US dollar is the most dominant reserve currency and China owns the largest foreign reserve holdings in the world. Despite smaller trade surpluses in China and narrower US trade deficits after the 2008 crisis, the bilateral US-China trade deficit reached another record level in 2011.

November 2011 was a significant month for east Asia. US President Barack Obama shifted the focus of US foreign policy from the Middle East to the Asia-Pacific region. In making economic issues “front and centre” in foreign relations, America plans to form an Enforcement Task Force, which will establish a rules-based order for open, free, transparent and fair trade practices, pertaining to currency, market access and intellectual property rights.

They will complement the other plans announced by Obama in 2010 and 2012 to boost the US export and manufacturing sectors respectively.

On the exchange rate front, the US urged the yuan and other surplus-led emerging currencies to appreciate, not only against the US dollar, but also the euro and the yen. The US Treasury currency report in December 2011 did not support unilateral interventions in Japan and South Korea, except during disorderly market conditions, and urged surplus-led countries to adopt a greater degree of exchange rate flexibility.

Finding a middle ground

To minimise the risk of currency wars evolving into trade wars, East and West need to work harder to prioritise cooperation over confrontation in achieving consensus to plot a sustainable path towards a more balanced world economy in the next decade. If the burden of adjustment falls too much on the indebted Western nations, it could exert severe recessionary and disinflationary pressures on the world economy. Conversely, disproportionate pressure on the surplus-led east Asian countries to boost domestic-led strategies that promote inflation, asset bubbles, trade and current account deficits and excessive bank leverage risk setting up the region for a boom-bust cycle in later years.

Looking ahead, the decade can still belong to east Asia. Crises can, if properly seized, turn out to be great opportunities. While the demand pressures on the external environment from the US/EU deleveraging should not be taken lightly, America has pronounced the Asia-Pacific as the world’s strategic and economic centre of gravity. Why?

America needs to deliver a credible fiscal consolidation plan after the US election to safeguard its remaining triple-A debt ratings. Structurally, the US fiscal deficit is still outpacing its economy, and will continue to push the federal debt/GDP ratio higher without reforms to reduce its reliance on private consumption and government spending to support economic activities. Herein lies the motivation for the White House to boost US trade and manufacturing activities, targeting more exports to Asia.

China’s next leaders, who assume the reins in 2013 for the next decade, favour services as the sector with the most potential to boost domestic demand. After freeing its yuan peg in June 2010, China has been working hard to internationalise its exchange rate. Its desire to integrate with the global financial system is reflected by its ambitious goals for the yuan to become a Special Drawing Right (SDR) currency in 2015, and make up 5-10 percent of world’s reserves by 2020. Similarly, Shanghai will work towards becoming a global yuan trading hub by 2015, and an international financial centre by 2020.

In conclusion, the bigger picture still favours a weaker US dollar against east Asian currencies longer term. Even so, this may be a theme best reserved for 2013 and the years thereafter. 2012 should, meanwhile, be viewed as a year for east Asia to lay the foundation – via structural reforms – to address global imbalances when the US starts its fiscal consolidation process from 2013.