William Shu first identified the need for Deliveroo when he made the move from New York to London in 2004. Surprised to discover a large portion of London’s best restaurants were unwilling to deliver, Shu made it his personal mission to connect customers with their favourite foods.

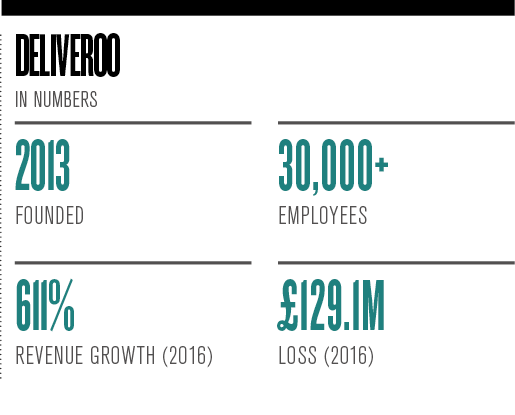

Ditching his job as an investment banker, Shu co-founded Deliveroo with childhood friend and software engineer Greg Orlowski in 2013. Driven by the motto ‘proper food, proper delivery’, Deliveroo now has an estimated value of $2bn (€1.7bn), employing more than 30,000 riders in 150 cities across Europe, Asia and the Middle East.

Unsurprisingly, Shu’s days are now filled with as much adrenaline as the riders who don the Deliveroo jerseys. He has become one of Britain’s most successful entrepreneurs, revolutionising an age-old service with a gig-economy business model based on a freelance workforce.

The main challenge facing the gig economy is the lack of a comprehensive

legal framework

Deliveroo’s creator and CEO is also a role model in London’s thriving business ecosystem, which, despite the uncertainty surrounding the ongoing Brexit negotiations, is considered to be the best environment for digital start-ups in Europe.

Taste of New York

At the beginning of Shu’s career, digital environments were very much confined to computers. But as he was cutting his teeth in the world of finance, digitalisation was spreading around the world, opening the door for disruption. As Shu recounted to a NOAH audience in 2015, it was his own frustrating experience with deliveries that spurred his creativity. Like many workers whose daily routines leave little time for fine dining, Shu wasn’t satisfied with the options available to him.

In Manhattan, Shu had been able to feast on the finest foods New York had to offer, with the city’s best restaurants offering affordable delivery services. In London, however, Shu found himself forced to choose between venturing to one of Canary Wharf’s supermarkets for a mass-produced sandwich, or waiting for orders to arrive at his desk from nondescript and unknown restaurants. “That upset me deeply, and that’s when I first started thinking about delivery,” Shu told the NOAH audience.

The old and the new

If you flick through any guide on entrepreneurship, you’re likely to find a similar set of guidelines for founding a successful company: first, you must detect a social necessity and fulfil it. Second, you must provide people with a value-added solution they’re willing to

pay for. And third, you must build an adaptable team capable of weathering any storms the future may hold.

David Cobb, a partner at Deloitte, also believes you need more than a good idea to create a prosperous tech business: “Since before the dotcom boom of the late 1990s, there have been lots of great ideas that just didn’t work because either the technology required was not yet available, or the need was not sufficiently acute in the minds of customers to drive the sort of rapid uptake needed to scale up.

“[Even in cases where the timing is right,] a business won’t scale if it doesn’t have a strong, dedicated and credible management team behind it to convince the market and raise the funds.”

With Deliveroo, Shu appears to have ticked all the boxes. While it’s true Shu didn’t come up with the idea of delivering food to diners’ doorsteps – some historians argue food deliveries date back to before the 20th century – it’s fair to say he approached an established industry with a fresh perspective.

As a ‘foodtech’ firm, Deliveroo has successfully combined new technologies and social habits with a traditional business model. Indeed, while delivery services like JustEat existed in London long before Deliveroo, Shu targeted local restaurants that lacked a pre-existing delivery structure, providing them with a new way to reach customers. Some may think there is nothing revolutionary in making deliveries on bicycles – especially considering Costa Coffee’s use of drones in Dubai – but in reality, Deliveroo’s true disruption was its gig-economy business model.

Shu on the other foot

The ‘gig economy’ is a phrase used to describe the growing number of internet-based technology companies propped up by short-term and freelance workers. Unsurprisingly, with no permanent jobs in place, the gig economy has been one of the most controversial innovations to hit the tech world in recent years, with the likes of Uber and Airbnb spreading the concept around the world. But as the phenomenon has grown bigger, so have the problems.

The main challenge facing the gig economy is the lack of a comprehensive legal framework, with governments the world over struggling to establish a set of rules for what is, by all accounts, a flexible and informal working structure. Tech expert and futurist Ben Hammersley believes there are “two simultaneous true stories” currently playing out: “The first is that many people around the world have supplemented their income and have increased their life quality thanks to gig work.

“However, these jobs don’t have any protection for employees – in fact, it’s controversial whether they’re employees at all. And this goes a long way to increase social inequality and add social problems in societies.” Hammersley believes it is this contradiction that makes the debate particularly difficult to resolve.

Amid its rapid growth, Deliveroo has been one of the companies struggling with this duality. In the UK, the company faces a legal battle with workers due to its payment system, which remunerates riders per delivery, rather than hourly. In 2016, Deliveroo was instructed by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy to pay workers the national living wage of £7.20 (€8.10) per hour, unless the Ministry of Justice or the HM Revenue and Customs authority deemed Deliveroo riders to be self-employed. At the time of writing, this issue remains unconcluded.

Deliveroo faces a legal battle with workers due to its payment system, which remunerates riders per delivery, rather than hourly

Earlier this year, the UK Government published an official report, known as the Taylor review, aimed at adapting employment laws for modern times. Shu made Deliveroo’s submission to the report public, also taking to The Telegraph to outline his desire for new rules: “We want to combine full flexibility with real security – and we are calling for the law to be updated so we are able to offer both.”

Unlike Uber’s transportation unit, which lost its licence to operate in London in September and at the time of writing is still appealing the decision, Deliveroo continues to operate without restrictions, and is expanding in the UK.

“What worries me about the debates related to the gig economy is that many of the questions raised, such as the minimum wage, have already been answered,” Hammersley said. “I’m sure that society will say yes if it’s asked to pay an extra £1 [€1.12] in a £30 [€33.72] order for Deliveroo to comply with the law. Otherwise, the law has to change… Businesses shouldn’t be allowed to ignore it.”

But if a new era needs new definitions, how far can disruptors truly go in breaking with tradition? From Cobb’s point of view, finding a balance is the ideal approach: “Those building today’s unicorns [companies valued at more than $1bn (€850.4m)] are questioning the status quo. These challenges are generally valid but often many of the rules are in place in order to protect customers, suppliers or the workforce.

“A balance is needed in order to drive genuine and meaningful change without taking things too far for regulators and governments to accept.” With companies like Deliveroo making a new model of work more prevalent, the time for new definitions seems to be drawing nearer.

New Editions

Despite these challenges, Deliveroo has achieved something most start-ups can only dream of: in just four years, the company has doubled the unicorn threshold of $1bn. Julian Birkinshaw, Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at the London Business School and author of several management books, attributes this feat to Shu: “From the thoughtful initial idea and a very aggressive growth plan, to his ability to scale up and build an organisation to support this business… This kind of entrepreneurship is not for the faint-hearted.”

Shu has also managed to attract investors, with Deliveroo receiving $860m (€732.6m) over several funding rounds. The latest, which was carried out in September, drew a staggering $385m (€328m). “This investment will take us to the next level,” Shu said in a statement released by the company. Expanding a little further, the Deliveroo CEO said the company planned to use the money to develop technology, expand the business into new locations and create delivery-only kitchens called ‘Editions’, which will allow food suppliers to get closer to high demand areas where they currently have no reach.

But Editions isn’t the only innovation Deliveroo has introduced to stay ahead of competitors like UberEats: in January 2017, the company created a subscription service, charging customers £8.99 (€10.15) per month. As a result of these market-leading developments, Deliveroo’s revenue witnessed a 611 percent increase in 2016, reaching £128.6m (€145m). Despite a drastic increase in sales, however, the company continues to operate at a loss of £129.1m (€145.6m).

According to Birkinshaw, Deliveroo’s performance is no surprise: “Every fast-growing start-up tends to make a loss, because they are investing so much in growing into new markets and building their capacity to manage their business ahead of demand.”

Birkinshaw drew comparisons to Amazon, which took years to record a full year of profit. Instead, the company worked its way to the top while operating at a loss, only increasing prices and broadening its offering once it had cornered the market. Although Deliveroo clearly has a long way to go to match the success of Amazon, the company appears to be on the right track. Just like Brian Chesky (Airbnb) and Travis Kalanick (Uber) before him, it appears Shu is leading a new generation of groundbreakers, pushing the boundaries of an established industry and redefining the rules of business.