Although the free movement of goods is one of the four fundamental freedoms of the European Single Market, it is not without its caveats. In order to sell goods across the 28-member bloc, businesses based outside the EU must ensure their products fulfil a host of regulatory criteria.

A small business looking to export electrical equipment from, say, India, would have to first produce the required technical documentation, ensure its products comply with various EU directives and then complete an EU declaration of conformity. Unsurprisingly, this process can be prohibitive in terms of both cost and time for smaller operators.

Such barriers are in place for good reason. Some of the requirements aim to ensure that consumers are kept safe; others protect them from being ripped off. Collectively, they help to maintain the integrity of the single market. It has been suggested recently, however, that the existing EU measures do not go far enough to ensure product compliance.

In December 2017, the European Commission published a proposal for new regulations regarding the surveillance of products entering the single market. The most eye-catching part of the new regulation was a requirement for manufacturers based outside the EU to appoint a designated person “responsible for compliance information established within the [union] to facilitate contacts with market surveillance authorities”.

Given the sheer quantity of non-compliant goods in the market, it is understandable the EU is trying to improve its market surveillance

The new legislation could help European regulators crack down on illegal products entering the single market, but businesses are understandably worried about the extra burden that will be placed upon them. If the proposal is approved, it could have major implications for businesses based in third-country markets that conduct a lot of trade with the EU, such as Canada, Japan and, potentially, a post-Brexit UK.

The cost of compliance

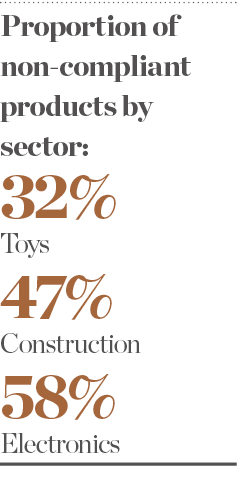

According to the European Commission, the quantity of non-compliant goods currently present within the single market is substantial. Up to 32 percent of toys, 47 percent of construction products and 58 percent of electronics do not meet the regulatory standards required for sale in the EU. This not only harms consumers, who may be receiving unsafe goods, it also damages the business landscape by putting compliant companies at a competitive disadvantage.

Given the sheer quantity of non-compliant goods in the market, it is understandable the EU is trying to improve its market surveillance. The proposed legislation would cover around 80 percent of the consumer goods sold within the single market, including items such as medical equipment and wireless electronics.

In total, the regulation covers more than 70 product categories, with businesses required to have a designated agent for each type of product they import. The chosen individual will then have their contact details included on every product that is sold, so there is clear accountability if any problems arise. Still, Maurits Bruggink, Secretary General at the European E-Commerce and Omni-Channel Trade Association, told European CEO there are a number of issues surrounding the proposed EU regulations.

“An online retailer based outside the EU will have to find the right representative person, or perhaps more than one if it is selling a diverse range of products,” Bruggink said. “How much is this going to cost? A representative will eat away at the retailer’s margins.”

The financial impact of the proposal is likely to have more of an effect on some retailers than others. Many SMEs already operate along extremely thin margins; if they have to recruit another member of staff or pay for legal advice to ensure they comply with the new legislation, many will be forced to stop exporting to the EU altogether.

“Large companies that benefit from economies of scale will manage, while small companies will find it too cumbersome and expensive to appoint a representative person,” Bruggink said. “There are already so many other hurdles, [such as] VAT, different consumer rules and cost of returns.”

Indeed, the majority of larger firms already have an appointed representative in place within their EU subsidiaries, making it easier to conform to new regulations. It’s the smaller firms that are more likely to struggle. Ironically, the measure – which was partly intended to improve competition by preventing firms from cheating the system – may price international SMEs out of the EU market.

Faulty reasoning

Although the proposed EU regulation still needs to clear a few hurdles before it comes into force, businesses are already concerned about its potential impact. The UK’s Federation of Small Businesses believes it could cost each company £1,500 (€1,729) per product category to hire an EU law firm to ensure compliance. If the regulations are approved, they will be enforceable from January 1, 2020, leaving little time for firms to prepare for such a substantial financial cost.

The other potential issue with the new EU rules is that they may not make much of a difference for illegal traders. Many of the companies currently importing non-compliant goods into the EU are not doing so out of ignorance of the rules, but rather in defiance of them. Bad actors are unlikely to bother employing a designated person – they will simply claim they have.

“Rogue traders may actually see the new proposals as an advantage,” Bruggink told European CEO. “They can simply tick another box and make it appear to the consumer and the authorities that all is fine.”

The rise of e-commerce sites like eBay and Alibaba means it is easier than ever for businesses located in markets with less stringent product standards to import their goods into the EU. Often, these goods are cheaper than those made in the EU, but they can also be dangerous or poorly made – or both.

Tit for tat

With US President Donald Trump seemingly intent on starting a trade war with anyone who threatens his country’s economic supremacy, there has been a lot of talk regarding the effect tariffs can have on the movement of goods and services. And it is certainly true that tariffs can be a particularly effective way of restricting imports. What the EU’s proposed legislation for product compliance shows, however, is that non-tariff barriers can also have a significant impact on international trade.

Although it is not the EU’s intention for the new regulations to spark retaliatory protectionist measures, there is a possibility the legislation will create a domino effect. “Other countries will perceive this proposal as a non-tariff barrier and will introduce similar measures,” Bruggink said. “This will hurt European online retailers trading to non-EU consumers.” As a possible alternative, Bruggink cited the decision by some online marketplaces to sign a voluntary ‘product safety pledge’.

“The European Commission has issued a voluntary code for marketplaces with best practices to guarantee product safety,” Bruggink explained. “One of the elements is maximising cooperation between operators and enforcement authorities. That is the way forward. Otherwise, any measure should always be risk-based. We want surveillance to focus on high-risk products like toys and not impose burdens on, say, [a] shoe seller.”

The reaction to the EU’s attempts to crack down on non-compliant goods highlights the difficult balancing act facing the European Commission. Too much regulation can be prohibitive for smaller firms; not enough undermines the single market. Consumer safety should never be compromised, but if bureaucracy ends up going too far, it will put small companies out of business.