Apple, Samsung, Alphabet, Alibaba, Amazon, Baidu and Tencent. The world’s biggest technology companies all have one thing in common: they originated outside of Europe. Although the EU is the second-largest economy in the world – behind the US in nominal terms and China with regards to purchasing power parity – nobody really considers the bloc to be a potential leader of the digital economy of the future. In other words, the continent that brought the world the printing press, the internal combustion engine and the world wide web is falling behind.

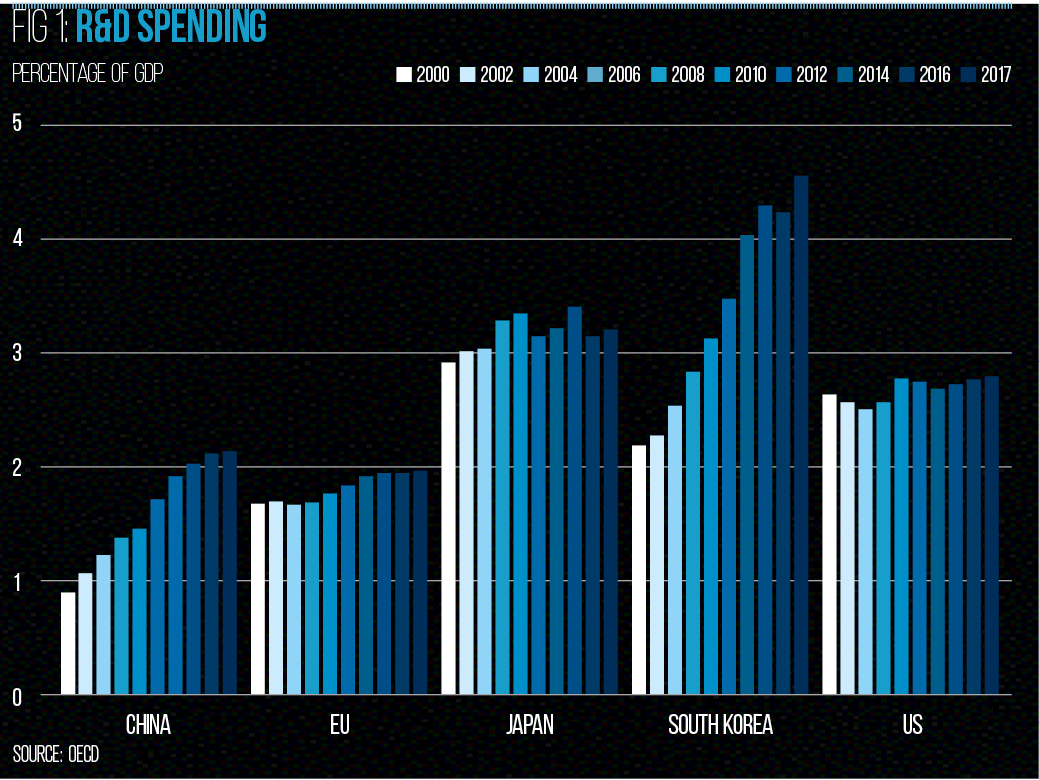

If Europe is to regain its place at the top table, it will need to put its money where its mouth is. For too long, the continent has allowed investment in research and development (R&D) – the foundation that underpins technological progress – to flounder. In 2000, the EU allocated 1.67 percent of its GDP to R&D, almost double that of China (0.89 percent). Since then, though, China’s commitment to researching new technologies has been relentless, overtaking the bloc in terms of R&D spending in 2012 (see Fig 1).

The EU also trails behind Japan, South Korea and the US in terms of R&D expenditure, but simply throwing money at the problem will not be enough to get it back in the race for technological dominance. Instead, cultural attitudes towards risk need to be challenged and regulatory frameworks must be reformed if they are shown to stifle innovation. Unfortunately, this may still not be enough, as the problem with neglecting R&D is that once you fall behind, it’s very difficult to catch up.

Out of service

While depicting the EU as some sort of innovation basket case would be a gross exaggeration, it does fare particularly poorly in certain fields. The bloc can still rightly lay claim to world-leading businesses in sectors such as automotive manufacturing, petrochemicals and financial services, but it has not been able to compete with the US or China when it comes to disruptive digital industries.

“Europe’s technology and IT sector risks falling behind economic powerhouses such as the US and China due largely to a lack of investment,” Mark Tighe, founder and CEO of R&D tax relief consultancy Catax Group, told European CEO. “Not one of the world’s 15 largest digital firms today is European, and the US is forecast to spend 175 percent more on IT development than Western Europe between 2018 and 2022, market intelligence firm [International Data Corporation] has warned.”

Europe hasn’t always struggled with innovation, though. In the early 2000s, Finland’s Nokia led the mobile phone industry and, around the same time, Skype made its way out of Estonia to dominate the nascent video-messaging market. In the space of a decade or two, however, these companies – and many others like them – have been supplanted by rivals from other countries.

The problem with neglecting R&D is that once you fall behind, it’s very difficult to catch up

Of course, Europe does still have a number of exciting technology firms, but their valuations are dwarfed by the likes of Apple, Microsoft and Alibaba. Stockholm-based music-streaming platform Spotify, for example, is estimated to be worth €20bn; by comparison, US e-commerce giant Amazon is valued at over $1trn (€893.5bn).

Even European technology firms with higher valuations than Spotify can hardly be considered disruptive in the same way as many of Silicon Valley’s household names – in fact, only eight percent of businesses in the EU are classified as ‘leading innovators’ in the European Investment Bank’s latest investment report. In the US, this figure is twice as high.

Part of the problem resides in the fact that although the EU has a common market for physical goods, it doesn’t have a corresponding market for services. When the mobile phone industry primarily concerned hardware, this wasn’t an issue, and the likes of Nokia and Ericsson were able to come to the fore. Today, however, smartphones are all about software, and the digital economy is all about platforms.

For digital firms founded in the EU, scaling up within national borders is easy enough; capturing customers across the entire bloc, however, is a more difficult proposition. There are language barriers to overcome and different market considerations to navigate. This makes it much more difficult to scale up quickly. A US start-up can capture a significant chunk of the country’s 327 million potential customers with a relatively homogenous business strategy. A Chinese firm can do likewise when targeting a population of 1.39 billion. While the EU may have more than 500 million inhabitants, grabbing the attention of all of them is far from straightforward.

Playing it safe

Another aspect of the EU’s R&D conundrum is a matter of culture: European entrepreneurs appear far more risk-averse than their counterparts elsewhere. Access to capital – particularly for unproven businesses – is more challenging to come by. What this means is that EU start-ups are forced to focus on revenue and profits from the get-go, while American and Chinese companies can prioritise growth. The latter approach has allowed firms like Netflix, Uber and Alibaba to accrue mountains of debt in exchange for market share.

While US venture capital investment reached a record $130.9bn (€116.6bn) in 2018, Europe registered a comparatively meagre €23bn. This divide comes despite the EU possessing a larger population than the US and a similarly sized economy. In addition, 40 percent of all venture capital in Europe comes from the public sector, which is known for being cautious.

“The key problem in Europe is not the lack of ideas and innovation itself, but the lack of risk capital and other investment pools available to nurture R&D,” Tighe explained. “This means European businesses are forced to look for finance elsewhere and often relocate as a consequence. Clearly, with greater incentives such as R&D tax relief, tax rewards for high-risk investments or lower tax rates for profits made from R&D-related work across the board in Europe, this can change.”

Europe is home to just 10 percent of the world’s unicorns (see Fig 2) – start-ups with a market valuation over $1bn (€896.7m) – with most of those located in the UK. Tighe believes that part of the reason this figure isn’t higher is due to European firms’ lack of access to the capital needed to scale, meaning they often have to look to China or the US for further growth opportunities. Skype is a case in point: while the firm was founded in Europe, it wasn’t too long before the company accepted an $8.5bn (€7.6bn) takeover bid from Microsoft.

If European firms are struggling to capture the capital they need to reach unicorn status, then governments could at least offer greater financial incentives for those that invest in R&D. Businesses also need to start shouldering some additional risk – this is especially important when you consider the potential rewards such risk can bring. According to Callaghan Innovation, returns for R&D expenditure average between 20 and 30 percent, which is significantly higher than investments in physical assets. Even if owners prefer a slow-and-steady approach to one of rapid expansion, investing in innovation is still the way to go. With the economy set to change markedly in the coming years, R&D is one way of future-proofing against the coming disruption.

Bureaucrats in Brussels

The EU is often blamed for holding back disruptive businesses and has gained a reputation for interfering and being overly bureaucratic. Certainly, the way in which it engages with US tech firms supports this view, with Google, Apple and Facebook all having clashed with European regulators in the past few years. When it comes to the European landscape, though, it seems the EU is not doing enough.

Fragmentation remains a major obstacle to the creation of world-class European businesses, with the different regulations, taxes and industry standards found across the union providing obstacles to cross-border investments. These are areas where the EU could do more to encourage uniformity, particularly with regards to R&D expenditure. While the likes of Sweden, Austria, Denmark and Germany all spent more than three percent of GDP on R&D in 2017, eight member states recorded an R&D intensity of below one percent.

Even if owners prefer a slow-and-steady approach to one of rapid expansion, investing in innovation is still the way to go

“Brussels is often an easy target to blame for any European shortcomings but, in the case of R&D investment, Brussels is more the solution than the problem,” Tighe said. “It is the fragmentation of different national economies and regulations, and [the] lack of coordinated policies, that holds Europe back by inhibiting cross-border investment and business growth. However, there is only so much EU policymakers can do, and it falls to individual national governments to cut red tape, create environments that foster R&D and to work closely with other European nations to ensure a unified approach. Europe needs to think as a global region if it is to compete with giants like the US and China.”

A similar story can be found when looking at Europe’s patent filing data. The European Patent Office (EPO) witnessed a 4.6 percent year-on-year increase in patent applications in 2018. Yet again, however, there is a lack of consistency among member states. “On a European scale, Germany is the most prolific patent filer, responsible for 15 percent of all patent applications received by the EPO,” explained Karl Barnfather, chairman of European intellectual property (IP) firm Withers & Rogers. “It is followed by France and Switzerland, each responsible for five percent and six percent, respectively.

“By comparison, the UK sits further down the rankings, responsible for three percent of the total patent applications received by the EPO last year. Cultural attitudes to the importance of IP are partly responsible for the disparity between the UK and some other European nations. Innovators in countries such as Germany and Switzerland are much more aware of the value of IP protection and its role in commercialising a company’s investment in R&D.”

In many respects, the EU has taken great strides in the promotion of common standards and joined-up thinking across national borders. The abolition of roaming charges in 2017, the General Data Protection Regulation and the second Payment Services Directive are all steps towards a unified digital single market. When competition comes from the likes of the US and China, though, the fragmentation that still exists between EU member states presents another hurdle for businesses and investors to overcome.

Chasing the horizon

Although the EU has a lot of work to do if it is to catch up with the markets that are currently leading the way in terms of innovation, there are signs the bloc is willing to accept the challenge. Horizon Europe, the EU’s €100bn R&D programme, is set to launch in 2021 and will look to support the cultivation of digital skills and the development of the businesses that rely on them.

The ambitious programme hopes to build on the progress already made by its predecessor, Horizon 2020, which is due to come to an end next year. Horizon 2020, which aimed to invest €80bn between 2014 and 2020, has been a success, albeit a qualified one. It has been responsible for issuing more than 15,000 research grants since 2014, and has supported technological developments in fields such as medicine, agriculture and astronomy.

There have been complaints, however, that the Horizon programme has not been forward-thinking enough, with critics arguing that it should back more ‘moonshot’ projects. “Public funding remains vital for backing certain types of R&D and longer-term projects where returns may not be seen for many years,” Tighe said. “The budgetary increase of Horizon Europe – the EU’s key platform for R&D investments – will, of course, help, but without policies designed to significantly increase private sector investment, it will not be enough to supercharge R&D in Europe.”

At present, the majority of research projects that receive support from Brussels come from the EU’s major economies – notably, Germany, France and the UK – but there have been calls for the Horizon Europe initiative to focus more energy on the EU’s poorer members in a bid to bridge the east-west divide. In particular, universities in Eastern Europe will require extra support if they’re to offer the infrastructure and salaries that can rival those of their western counterparts.

The EU must ensure that businesses are not straitjacketed when it comes to conducting cutting-edge research

Money alone, however, is unlikely to be enough. Universities from Western Europe also have more experience of the funding process and the knowledge of how best to structure a funding proposal. Closer collaboration between institutions based in different EU states could be one way of ensuring that promising research proposals hailing from outside the tech hubs of London, Paris and Berlin do not get overlooked.

Scaling the heights

For all the talk about Europe’s innovation struggles, the continent has no lack of great ideas or, indeed, start-ups. It is during the process of scaling up that companies generally struggle. At this point, they often either seek acquisition by larger overseas firms, or they collapse. This creates the impression that ‘home-grown’ success stories are hard to find.

“In Europe, SMEs and growing companies struggle to find the capital they need to commercialise and scale up due to smaller-risk capital markets,” Tighe said. “Investment in the early stages of business development – bringing an idea to market – were nine times higher in the US than in the EU in 2015, according to the Association for Financial Markets in Europe. The gap widens even more when it comes to scaling up. Later-stage venture capital investments were 20 times higher in the US than the EU in 2015.”

If European start-ups cannot get the support they need locally, then partnering with global firms may be necessary. The Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres, for example, recently opened a new office in Tel Aviv, Israel, in order to tap into the exciting developments taking place in the fields of data science and energy research. Collaborating with Chinese researchers should also be a consideration.

Although China is racing ahead while scientists in the West are tied up by regulatory red tape, there is no need for Europe to compromise on its own ethics in order to compete. Europe’s high regulatory standards are something to champion, but they should always be open to discussion. Put simply, the EU must ensure that businesses are not straitjacketed when it comes to conducting cutting-edge research.

“The lack of funding is the key element holding back innovation in Europe, but the reasons for this lack of funding are themselves multiple,” Tighe said. “It is driven by a combination of a risk-averse business culture, government policy and regulation, and [a] lack of cross-border unity, to name just a few.”

New technologies in fields such as artificial intelligence, virtual reality and biomedicine will be the main driver of economic growth and prosperity over the next decade, but they will only emerge in Europe with significant long-term R&D investment and a substantial shift in mindset. Perhaps the most damning indictment of the continent’s current attempts to play a leading role in the global economy of the future is that, as people wonder whether the US or China will come out on top, Europe is barely an afterthought.