When European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen unveiled the European Green Deal in December 2019, she heralded it as Europe’s “man on the Moon” moment. This was no exaggeration: making Europe the first carbon-neutral continent will require nothing less than a seismic shift in policy across every sector, from energy to finance to agriculture. In short, the Green Deal has the potential to fundamentally change the way we live and conduct business.

Inevitability, such a radical plan with far-off goals has evoked scepticism. Some analysts question whether the plan will trigger the “green investment wave” that von der Leyen has promised; climate activists and environmental organisations, meanwhile, argue the plan doesn’t go far enough to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The Green Deal has the potential to fundamentally change the way we live and conduct business

The Green Deal also faces a new obstruction, unprecedented in modern times. Since March 2020, COVID-19 has taken centre stage, relegating the global climate crisis to the sidelines of national policy. Sofia López Piqueres, a policy analyst at the European Policy Centre, told European CEO that this sudden shift in priorities poses a serious threat to the Green Deal’s survival.

“Given that the record of national political leaders… juggling multiple crises at the same time is extremely bleak, many of the measures announced in the Green Deal are indeed at risk,” she said. “For starters, many initiatives – such as the new [EU] strategy on adaptation to climate change – will likely be delayed, and we could well expect a watered-down level of ambition in member state capitals across most legislative and non-legislative files.”

It’s because environmental policy has so often come second to other government initiatives that we find ourselves in the situation we do now, with drastic action required to prevent a climate catastrophe. Through the Green Deal, the EU has the opportunity to promote decarbonisation around the world. But in the face of political resistance, budgetary constraints and a looming economic crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, the bloc could all too easily fail to put words into action.

Leading the charge

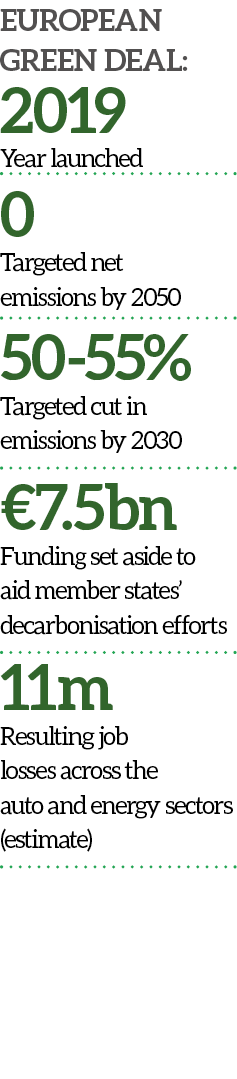

Core among the Green Deal’s goals is achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and cutting emissions by 50-55 percent by 2030, compared to 1990 levels. To achieve this, the EU has proposed a green investment drive worth €1trn. Almost half of that funding will come from an existing plan to allocate a quarter of the EU’s budget to green causes. An additional €100bn (or more) is expected to come from member states, while EU guarantees aim to attract €280bn from the private sector.

The plan includes a host of ambitious measures that would overhaul the European economy. These range from tripling the renovation rate of buildings to creating a “green and healthier” agricultural system that makes the environment “pollution-free” by 2050. The EU wants to achieve all of this without reducing prosperity among its member states – a tall order, to say the least.

One of the Green Deal’s most contentious proposals is a carbon border adjustment mechanism. Should it go ahead, the measure would alter the price of imports according to their carbon content. It remains to be seen how this would work in practice: many analysts point out that accurately calculating the carbon content of imports is a huge logistical challenge. There is also a considerable risk that external countries will label the scheme protectionist and retaliate with sanctions of their own.

However, such a mechanism could compel other countries to strengthen their climate policies and reduce fossil fuel consumption to trade freely with the EU. It may even create a global trading system focused around low-carbon goods. Even if the EU becomes carbon neutral, this will have little impact on global warming unless other countries follow suit, so measures with an international focus are extremely important.

Devil in the detail

Such initiatives speak to the sheer ambition of the proposal. Another bold component is the Circular Economy Action Plan, which aims to improve resource efficiency across products’ entire life spans.

“Evidence suggests that about half of the world’s [greenhouse gas] emissions are related to material requirements,” Vasileios Rizos, Head of Sustainable Resources and Circular Economy at CEPS, told European CEO. “Therefore, achieving the carbon-neutrality objective in the EU is not possible if we do not change the way we use and manage resources.”

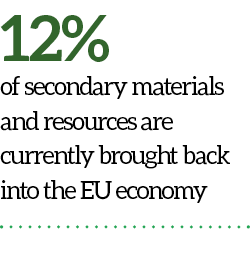

Today, only 12 percent of secondary materials and resources are brought back into the EU economy, according to a statement by the European Green Deal’s Executive Vice President, Frans Timmermans. Transitioning from a linear economy to a circular one will require a huge regulatory push.

“The 2020 Circular Economy Action Plan raises the bar on circularity ambitions in various fields,” Rizos said. “It sets up the principles for a new sustainable product policy framework focusing on product groups with high environmental [footprints] and circularity potential – namely electronics, IT, textiles, furniture and construction products. Some of the key listed initiatives are [the] introduction of ecodesign requirements for non-energy-related products; establishment of a European data space, including data on value chains and products; [a] proposal for minimum mandatory green public procurement criteria; and [a] revision of EU consumer law to support [the] availability of repair services.”

While millions of jobs will be lost, the European Commission believes investing in green technology will ultimately spur prosperity

These initiatives could have a profound impact, particularly on companies working in the manufacturing sector. While the ‘right to repair’ law could prove popular with consumers, it’s unlikely to go down well with manufacturers like Apple. Nonetheless, the EU claims that a circular economy will increase GDP some 0.5 percent by 2030 and create around 700,000 new jobs.

Ultimately, though, the Circular Economy Action Plan suffers from the same shortcoming as the broader Green Deal: a lack of detail. “The new plan includes a diverse set of legislative and non-legislative initiatives, however the details are missing at this stage,” Rizos explained. “The plan is very ambitious, but its success will depend on the details and implementation of all these actions.”

For this reason, Eric Heymann, a climate policy and transport sector analyst at Deutsche Bank Research, believes the promises made in the Green Deal should be taken with a pinch of salt. He told European CEO: “It’s probably not the task of a communication such as the Green Deal to give answers to all questions. Concrete investment programmes and incentives have to follow and have to be agreed on a European level – no easy task.”

A blank Czech

Indeed, not everyone has bought into the vision. The Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland all want financial guarantees before committing to decarbonisation, owing to the fact they are still heavily dependent on fossil fuels – in 2016, coal accounted for roughly 50 percent of the Czech Republic’s energy mix, and more than 90 percent of Poland’s. “Countries with a high share of fossil fuels in electricity generation and a high cost of manufacturing in total gross value-added will have more problems and higher costs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” Heymann told European CEO.

It was because of this that Poland refused to sign up to the EU’s climate-neutrality target in December 2019. As the country’s prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, put it: “Poland will be reaching climate neutrality at its own pace.” The Czech Republic has been another obstructive force, with Prime Minister Andrej Babiš telling reporters that “Europe should forget about the Green Deal now and focus on the coronavirus instead”.

“The Polish, Czech and Hungarian governments are the ones [that] have given the commission the biggest headaches,” López Piqueres said. “They argued that not all member states start from the same point and, therefore, the pace towards climate neutrality should be adapted to each of them. Moreover, they insist that the EU step up its efforts to cushion the economic impact of the transition in the less wealthy countries by showering them with generous funds.”

To ease the burden of decarbonisation, the EU created the Just Transition Mechanism, which allows member states to access a portion of a €7.5bn fund. As the most fossil-fuel-dependent nation, Poland could receive as much as €2bn, but the country’s policymakers fear such funding won’t stretch far enough. The IndustriAll European Trade Union has similar concerns. “The €7.5bn – if we get it, because the negotiations are still ongoing – is peanuts,” General Secretary Luc Triangle said at a policy forum discussing the Just Transition Mechanism in February. As a result, Poland and many other Central and Eastern European countries have argued that they should be the only recipients of the fund. Germany, meanwhile, has rejected the idea of enlarging the fund to finance Poland.

Empty promises

The European Commission claims the Green Deal represents its “new growth strategy”. While millions of jobs will be lost – potentially 11 million across the automotive and energy sectors, according to IndustriAll – the commission believes that investing in green technology will ultimately create jobs and spur prosperity. This, however, depends on whether the level of investment is high enough.

The Just Transition Mechanism is the only portion of the Green Deal’s budget earmarked as fresh funds. The remainder is either reshuffled from existing EU funds or is expected to come from governments and private companies later down the line. This means the promised €1trn of investment is currently intangible.

What’s more, €1trn is considered by many analysts to be too small. Bruegel research fellows Grégory Claeys and Simone Tagliapietra estimate that the bloc needs an additional €300bn per year over the coming decade to meet its 2030 targets: “Even if the commission succeeds in mobilising €1trn of investments over 10 years, this would just represent a third of the additional investment needs associated with the European Green Deal.”

López Piqueres agrees that the plan itself is not sufficient, pointing to the reduced size of the EU budget as a key issue. With limited EU funds, the financial burden is passed onto national governments and the private sector. The EU, therefore, needs to create the right conditions to spur investment from these players by harnessing its fiscal framework.

The greatest challenge facing the European Green Deal is ensuring the COVID-19 pandemic doesn’t sink it altogether

As López Piqueres told European CEO: “First and foremost, member states should fully implement existing environmental and climate policies. The EU must also revise the EU Emissions Trading System… to align it with the climate-neutrality goal. Practically speaking, the EU should eliminate free allowances, strengthen the cap on allowances to align it with the more ambitious emission reduction target, reduce the surplus of allowances and, most importantly, fix an [EU Emissions Trading System] price floor that would rise at a fixed annual rate. In addition, the EU should strengthen its energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emission reduction targets to deliver deeper emissions cuts.”

But strengthening targets provides no guarantee the EU will meet them; the bloc’s record for delivering on climate promises is mixed. In 2017, renewable energy represented 17.5 percent of the energy consumed in the EU, suggesting the bloc was on track to meet its 2020 target of 20 percent. However, a 2019 report by the European Environment Agency concluded that the EU would likely miss its Paris Agreement climate targets for 2020 and 2030.

Since the Green Deal has now increased the bloc’s carbon emissions reduction target from 40 percent to 50-55 percent, the EU has set an even harder task for itself – one it may not measure up to. What’s more, the EU has been accused of misspending money intended for green projects in the past: in 2017, a report by EU auditors revealed that farmers had been paid to undertake environmentally friendly measures they would have used anyway, such as crop rotation.

“Given that EU legislation suffers an overall lack of implementation and a chronic gap between words and action, and that a recession is around the corner, there remains a fair amount of doubt regarding the achievement of the climate-neutrality goal,” López Piqueres told European CEO.

Out of the frying pan

For now, the greatest challenge facing the European Green Deal is ensuring the COVID-19 pandemic doesn’t sink it altogether. Governments are using huge cash injections to keep their economies afloat during the crisis and, in March, the European Central Bank unveiled a €750bn stimulus package to fight against the economic ramifications of the pandemic. Analysts fear clean energy investments will be forgotten amid the chaos, with member states inadvertently locking the EU into a fossil fuel economy for the foreseeable future.

“Member states must stop subsidising the fossil economy and shift that funding to renewable energy and energy-efficiency measures, and climate-proof all investments in the EU,” López Piqueres said. “This is all the more important now that member states are working on the recovery packages. In 2009, G20 leaders agreed to phase them out in the medium term but they have remained stable, distorting the energy market and inhibiting investment in the energy transition.”

Rizos is optimistic the EU will drum up enough support to continue pursuing its green goals while economies recover from the virus: “There are concerns that the coronavirus could delay or even weaken the actions included in the European Green Deal. Still, recent initiatives such as the call of the European Council for preparing a recovery plan integrating the green transition – as well as the alliance of ministers, CEOs, NGOs and trade unions calling for green recovery – signal that the Green Deal will be a central pillar of the recovery process.”

The coming months – and, indeed, years – will test the EU’s ability to juggle multiple crises at once. With the bloc headed for a steep recession in the wake of COVID-19, it is now setting its sights on a post-pandemic recovery plan. Nations have called for the EU to integrate the Green Deal into the heart of this plan, as true economic resilience will only come when the bloc addresses the climate question in tandem with the pandemic threat. Once the COVID-19 crisis is over, the EU must be prepared for an even longer battle.