Bill and Melinda Gates. Barack and Michelle Obama. Hugh Grant and the tea lady from Love Actually. Office romances have spawned many of our best-loved power couples, but also some of the most high-profile scandals in business history.

One of the latest romances to rock the business world came in November 2019, when McDonald’s CEO Steve Easterbrook was ousted for having a consensual relationship with an employee. McDonald’s policy forbids dating between employees with a direct or indirect reporting relationship.

The firing shocked many in the business world. Since he took the job in 2015, Easterbrook has been credited with almost doubling the company’s share price. He was behind its tech push, introducing self-order kiosks and investing in voice-activated drive-through technology. After his departure was announced, the value of McDonald’s shares fell by three percent.

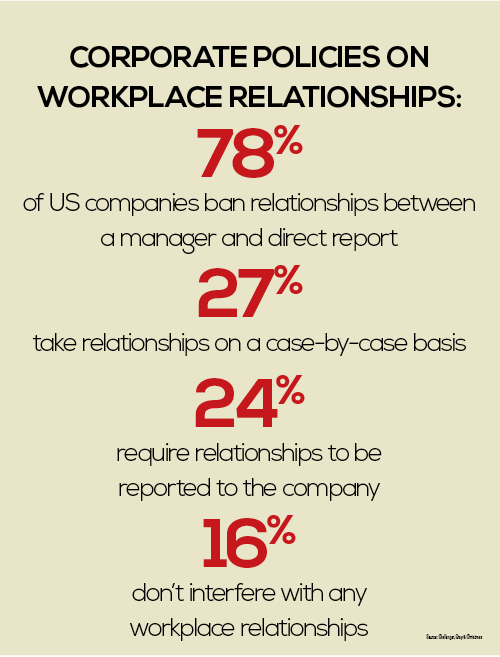

Easterbrook was the fifth US CEO to lose his job over a consensual relationship within 18 months. Ever since sexual abuse allegations against Harvey Weinstein highlighted power imbalances in the workplace, many US companies are erring on the side of caution and adopting zero-tolerance policies regarding relationships between managers and junior staff. Among US companies with formal policies on consensual relationships, 78 percent now ban them outright if they are between a manager and an employee.

It’s difficult to guarantee consent when one person is paying the other’s salary

But the same cannot be said of Europe, where a worker’s right to date who they want – and keep it private – is respected under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Many countries’ labour laws also enshrine this right. For example, when the German subsidiary of Walmart tried to ban flirting between coworkers in 2005, a court in Düsseldorf ruled that it was acting outside of the law.

Predictably, media outlets in Western Europe railed against Easterbrook’s firing. The French newspaper Le Monde criticised McDonald’s for “Anglo-Saxon puritanism” that was “far from French custom”. But attitudes are changing: as companies in the US crack down on sexual harassment, it is becoming obvious that workplace romances are far from clear-cut. It’s difficult to guarantee consent when one person is paying the other’s salary.

Love is in the air

For as long as there’s been a workplace, people have argued that romance has no place in it. According to historian Jane Humphries, early factories were deliberately segregated by gender to prevent heterosexual relationships from developing. To many, it made financial sense: if a female worker got married or became pregnant, she would have to leave her job. Then, as women started to join the workforce en masse, the stigma took a different form. “Classical organisational theory holds that sexuality and other ‘personal’ forces are at odds with productivity and out of place in organisational life,” Vicki Schultz, a professor of law at Yale, explained in her 2003 paper The Sanitised Workplace. Seen through this lens, a heady office romance is an unwelcome distraction from work. Schultz argues that many still see workplace relationships as

inappropriate for these reasons.

This is bad news for the world’s singletons. Although a growing number of people are partnering up online, the office remains a common place for people to find romance. It’s difficult to determine exactly what proportion of us has dated a colleague; a survey by Vault.com puts the number at 58 percent. Chantal Gautier, a business psychologist at the University of Westminster, thinks companies need to realise romance is just part and parcel of work. “Organisations are recruiting based on shared values and like-mindedness,” she said. “You could say that they unwittingly create the perfect playground for romances to flourish.” And of course, these aren’t always flash-in-the-pan romances. One study of 2,000 office relationships found that they are more likely to end in marriage than pairings that began online or through a friend.

As for the concern that workplace romances affect productivity, Gautier explained that sometimes the opposite is true. “When I did some research on this several years ago, my interviewees told me that, because they were so petrified of being stigmatised in the office, their productivity actually increased,” she said. Studies also show that workplace romances are generally well received by coworkers.

If relationships at work don’t affect employees or the organisation’s culture, then surely there’s no problem. But each couple is different, and these observations are only true of relationships between coworkers who are of a similar standing in the office hierarchy. When it comes to relationships between managers and their direct reports, things are much more complicated.

Mixing work and pleasure

According to Amy Baker, Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of New Haven, psychologists are cautioned against entering into what’s called a ‘multiple relationship’. This is a scenario where a personal relationship could feasibly affect their professional judgement. “Most certainly, a boss and subordinate dating would qualify as a multiple relationship,” she added.

Overzealous surveillance of office romances shouldn’t compensate for a lax approach to harassment

Something often flagged is the risk of favouritism. Managers are expected to keep their personal feelings out of the equation when reviewing an employee’s performance or discussing their salary. This would, of course, be difficult if they were dating said employee. Even if they succeeded in treating their romantic partner like any other worker, the more junior person could still face consequences. One study asked participants to look at fake profiles of workers at a law firm and determine who should be put forward for promotion and who shouldn’t. Consistently, the participants decided that any candidate dating a senior member of staff should be denied promotion. Far from giving someone a leg up on the corporate ladder, a relationship with a manager could very well do the opposite.

This dynamic also makes breaking up more difficult. Vanessa Bohns, Associate Professor of Organisational Behaviour at Cornell University, told European CEO: “By ending the relationship, you not only risk offending a relationship partner, but also the person who conducts your performance reviews and makes decisions about your salary and promotions.” If someone has to leave their role because of a break up, it’s likely to be the junior employee, who represents less value to the company. This outcome is far from ideal. Gautier added: “Transferring someone to another department or company is almost like you’re punishing that person.”

But this is hardly new information, and it doesn’t explain the recent spike in CEO firings. Instead, we may attribute that to the growing conversation about consent in the workplace. The sexual abuse allegations against Harvey Weinstein show that top executives can all too easily exploit their positions in order to abuse junior staff – most often, young women. At the same time, the Weinstein case demonstrates how difficult it can be for junior staff to reject the advances of someone with financial leverage over them.

Risky business

In one study, Bohns asked students to imagine a scenario in which a person asks their colleague on a date, either from the perspective of the suitor or target. Those thinking as targets reported that they would feel worse and more uncomfortable rejecting their coworker’s advances than the suitors imagined. “We may think someone has consented enthusiastically to a request to go out on a date, when they may have felt pressure to agree,” said Bohns.

More CEOs now lose their jobs due to ethical lapses than poor financial performance

Consent can be difficult to guarantee when one party influences the other’s financial wellbeing and career trajectory. Monica Lewinsky reflected on this in an interview with Vanity Fair. Previously, she had maintained that her relationship with Clinton was consensual; he had only abused her in the sense of throwing her under the bus when the two were investigated, she said. In 2018, she re-evaluated: “I now see how problematic it was that the two of us even got to a place where there was a question of consent. Instead, the road that led there was littered with inappropriate abuse of authority, station and privilege.”

When Clinton’s affair with Lewinsky came to light in 1998, consent wasn’t an issue the media explored. Instead, she was painted as a “ditsy, predatory White House intern”. Revisited through a post-#MeToo lens, it’s hard not to see an abusive edge to the relationship between a 22-year-old intern and her 49-year-old boss, who was also one of the most powerful people in the world.

On these grounds, some argue that a romantic relationship between a manager and their direct report is inherently an abuse of power. But this stance is problematic too. Gautier points out that such assumptions can fuel an infantilising portrayal of women. “There’s this stereotypical view that the junior female in that relationship is considered weak, vulnerable,” said Gautier. “But if they’re two consenting adults, where is the vulnerability there? We’re just making the assumption that the woman at the junior end can’t take care of herself.”

That said, a laissez-faire approach to sexual politics can help harassers. There have been times when France’s notoriously relaxed attitude to sex has allowed it to turn a blind eye to the transgressions of top executives. When Dominique Strauss-Kahn, Managing Director of the IMF, was accused of sexually harassing a subordinate, the French media mostly laughed it off. French newspaper Le Journal du Dimanche dubbed him le grand séducteur (the great seducer). But it’s hard to see what distinguishes Strauss-Kahn’s ‘womanising’ from the behaviour of sexual predators like Weinstein.

Easterbrook’s firing is part of a wider movement towards holding top executives to account. PricewaterhouseCoopers found in its annual CEO Success study that more CEOs now lose their jobs due to ethical lapses than poor financial performance. Boards are making these decisions to set an example at the top and prevent harassment in the office. But it’s a delicate balance to strike; over-regulation of gender relations at work can have the adverse effect of undermining #MeToo’s broader vision.

Spanner in the works

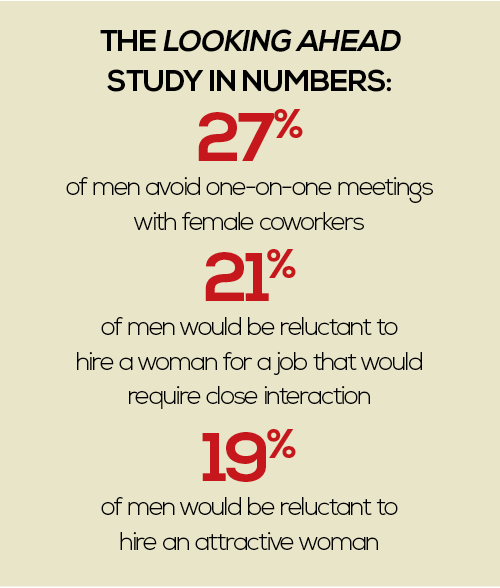

The #MeToo movement radically changed attitudes towards gender relations in the workforce; adjusting was never going to be an easy ride. A new study titled Looking Ahead: How What We Know About Sexual Harassment Now Informs Us of the Future found that men are more reluctant to interact with female colleagues following #MeToo, with 27 percent of men saying they now avoid one-on-one meetings with female coworkers.

One of the arguments often made against #MeToo is that harassment is hard to define. In a Bloomberg report, one Wall Street executive said men were now “walking on eggshells” around women because they no longer knew what behaviour was acceptable and what wasn’t. But this study found that, to the contrary, men and women generally agree on what constitutes harassment. “The idea that men don’t know their behaviour is bad and that women are making a mountain out of a molehill is largely untrue. If anything, women are more lenient in defining harassment,” said Leanne Atwater, one of the study’s authors, in the Harvard Business Review.

As a result of such findings, some have accused men of punishing women for the #MeToo movement. But condemning the men who’ve failed to adjust to a post-#MeToo workplace could shut out those whose minds need to be changed the most. Recognising these feelings and trying to understand them could be an important part of changing the climate around sexual harassment. “We need to get to the root of this discomfort,” Belle Rose Ragins, a professor at the Lubar School of Business, told the World Economic Forum. “Is it because the male mentor is afraid he may be sexually attracted to his female protégé? Does he fear others will misinterpret their relationship as sexual? Or is he afraid his female protégé may misinterpret his actions as sexual in nature?” The trouble with a hard-line approach to office romances is that it could fuel misunderstandings around the #MeToo movement and what it represents, rather than create a safer and more inclusive work environment.

The importance of culture shouldn’t be underestimated: a healthy office environment could be key to determining whether a workplace romance constitutes, or could evolve into, an abuse of power. “If you are in an environment that is toxic – where the culture is unhealthily competitive, top-down driven, or where people do not trust one another – the relationship itself may be problematic,” said Gautier.

Regardless of what policies a company adopts, it’s almost inevitable that romance will blossom in an organisation. While these relationships can take a turn for the worse, banning them outright is unlikely to be the most effective way of managing negative outcomes. More likely, it will push the relationship underground. “From the organisational side of things, eventually the relationship is found out and coworkers may feel betrayed and lied to,” said Baker. “For the couple, there is research suggesting that secret relationships are actually less satisfying – it is a drain to always be hiding your feelings.”

Policing office romances was the knee-jerk reaction to the many sexual harassment cases that came to light as a result of the #MeToo movement, but it is not a solution. In the case of Easterbrook, an uncomfortable context may have pushed the company to make a strong statement about workplace relationships. In the space of about three years, employees have filed more than 50 sexual harassment complaints against McDonald’s; class action suits accused the company of a “toxic work culture”. Against this backdrop, the organisation must have felt that it couldn’t risk any more negative press about inappropriate relations, particularly not in its upper echelons.

But overzealous surveillance of office romances shouldn’t compensate for a lax approach to harassment. Instead of criminalising workplace romances, human resources departments must make their harassment policies more robust. A growing body of evidence suggests that women are repeatedly let down by their companies when they report harassment. Alarmingly, some studies have shown that sexual harassment training can actually make people more cynical about a victim’s plight. In this context, consensual workplace relationships are an easy target for human resources departments – but they’re not the right one.