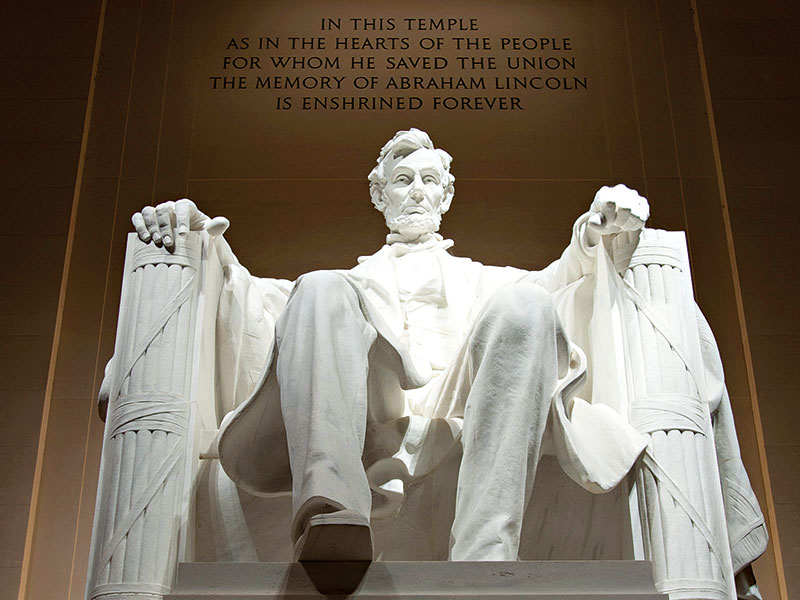

For centuries, it was thought that great leaders were born, not made. Many have professed that the Caesars, Lincolns and Gandhis of the world were born to accomplish greatness – to command and inspire hundreds, thousands or even millions.

Those who subscribed to this school of thought supposed that great leaders have innate qualities that cannot be taught. In the 19th century, this notion was named the ‘great man’ theory by historian Thomas Carlyle, who argued that people do not enter the world with equal abilities and talents. The very best leaders are born with distinctive capabilities, enabling them to captivate the masses.

“Shakespeare called them ‘becoming graces’,” said John Adair, author of Lessons in Leadership and How to Lead Others. Adair also listed some of the qualities that make a great leader: “Enthusiasm, integrity, [being] tough or demanding but fair, warmth or humanity, and humility – no arrogance or self-importance.” Arguably, many of these qualities are intrinsic – can warmth, for example, be taught?

We see it in everyday life too: there are certain people we meet who have a natural charisma, a way with people and words that brings out the best in others. They inspire and motivate, doing so with positivity, not threats or fear. In these cases, one can recognise a natural inclination to lead that is present in some and absent in others.

Born this way

Other attributes that are often linked with great leadership include vision, decisiveness, positivity and an ability to build confidence and solve problems. Regrettably, not every person in a leadership role displays these qualities: often, people fall into management positions due to expectation, automatic career progression or a simple case of timing. This marks the difference between a manager and a leader. Co-author of The Leadership Lab Chris Lewis noted: “Managers do things right. Leaders do the right thing… Management is the domain of actions. Management has a ‘to-do’ list. Leadership has a ‘to-be’ list.”

Often, people fall into management positions due to expectation, automatic career progression or a simple case of timing

This falls in line with the belief of Peter Drucker, widely known as the father of management, who once said: “Leadership requires talent. This gift is rare. In the world of management, the best managers are in limited numbers, and the leaders among them are many times less.” Bad managers – of which there are plenty – fail to engage their workforce, which leads to a loss in both productivity and talent. The end result could be disastrous for a company, costing hundreds of thousands (if not millions), in addition to an incalculable number of lost opportunities.

But appointing individuals with a natural proclivity for leadership is no easy feat: assessing a candidate’s ability to think holistically and take bold action when needed, while always respecting and helping others, is a hard ask. What’s more, an individual with these qualities doesn’t necessarily make a good leader.

“The modern descendant of the great man theory of leadership – namely that all you need is a charismatic or transformational CEO at the top, give him or her complete power and a massive salary and your troubles are over – is very wide of the mark,” Adair told European CEO. He argues that good management is necessary at all levels of a business, from day-to-day operations to company-wide strategy. “It is the teamwork of this network of leaders that delivers the goods,” he explained.

Lessons to be learnt

There is, however, an argument in stark opposition to the great man theory. According to some behavioural psychologists, great leaders can be made. Adair said: “We now know that leadership can be learned. There is no one in – or destined for – a leadership role who cannot significantly improve his or her contribution to the common good as a leader, providing, of course, that they are prepared to invest some time and effort towards that purpose.”

Certain skills can be picked up and honed over time, Lewis explained: “Most entrepreneurs will tell you that they learned their skills because they had to. They were either compelled to learn or they had no alternative.” In cases where there is no alternative, leaders are forced to think outside the box and maximise the resources available to them in order to achieve results. The ability to adapt can be improved and mastered with each obstacle that must be dealt with.

The ability to adapt can be improved and mastered with each obstacle that must be dealt with

Great leaders never stop learning, whether through day-to-day challenges, their personal relationships or the people they work alongside. With each challenge comes a new experience, a different way of thinking or an invaluable lesson in understanding others. The skill of observation is therefore key, but this is not necessarily innate: it can come with time and practice.

It is important to note, however, the distinction between being taught and learning. “There’s a role for business education, but the problem with that is it tends to hone analytical skills,” Lewis commented. Adair agreed: “It is learning by doing, not being lectured at, as the leadership academics do.” In other words, practical exercises and group discussion can bring out one’s ‘inner leader’. Constant observation and self-awareness, meanwhile, can ensure that leadership skills are enhanced over time.

Nature and nurture

That some people are born with certain talents and attributes that increase their suitability for certain roles is difficult to dispute. University College London has undertaken research to prove that an inherited trait is involved in producing a great leader. The study, published in 2013 by The Leadership Quarterly, was the first to identify a genotype correlated with a tendency towards leadership roles. “We have identified a genotype, called rs4950, which appears to be associated with the passing of leadership ability down through generations,” said lead author Dr Jan-Emmanuel De Neve in a press release.

Such a genetic gift, which could well be inherited, should be recognised and nurtured. Adair told European CEO: “A natural talent for leadership – which may show itself in the early years and be commented upon by others – especially calls for development. Indeed, anyone with a natural gift for leadership has [a] moral responsibility to develop that talent and put it to profitable use. Why? Because this world… stands in pressing need of good leaders and leaders for good.”

The ‘nurture’ aspect of leadership remains essential. Without it, a great leader could just end up being an adequate manager. Through continued learning, practical experience and collaboration, certain tendencies can be polished. Numerous moving parts make a good leader; natural qualities are involved, but these are enhanced by skills and lessons learned over time. A willingness to adapt and learn from others is crucial.

Only through a combination of these inherent qualities and learnt skills can great leadership be achieved. In terms of the age-old argument of nature versus nurture, Adair explained: “It is not either/or, but both/and.”