For decades, the vast majority of us have spent our time in an office environment slogging away for eight hours a day, five days a week. Whether you require less time to do your work or not, or even if such hours are affecting your overall wellbeing, it’s simply the status quo.

Now, of course, some companies are starting to mix things up, introducing flexible working hours and presenting employees with the chance to work from home. Yet, despite a growing body of evidence pointing to its outdated, unproductive and even unnecessary nature, the eight-hour workday persists as the de facto modus operandi.

“The eight-hour workday is a relic of 19th-century socialism – when children as young as eight worked the coal mines – and was first put into law in 1938 in the US, 81 years ago,” said Steve Glaveski, entrepreneur and author of several books, including Employee to Entrepreneur: How to Earn Your Freedom and Do Work That Matters.

“The nature of work has changed so much since then – most of us are no longer engaged [in] algorithmic, assembly-line tasks, but [in] tasks that require thinking. The thing about thinking is that we can only really do about four hours of deep thinking per day. We should place more emphasis on outcomes (such as the value created), rather than inputs (such as hours).”

Parkinson’s Law

By focusing on hours instead of outcomes, companies are not getting the most out of their talent and employees are not getting the most out of their days. Modifying this corporate mindset will become even more pertinent as the nature of the work we undertake shifts in tandem with technological progress. As artificial intelligence and machine learning take on repetitive assignments, for example, workers will have more time to engage in tasks that computers can’t do, such as those that require creative thinking.

Parkinson’s Law suggests that if one is given more time than needed to complete a task, then said task will become more complex and time-consuming

Naturally, such a cultural shift in the working world would be monumental. To achieve it, we will need to critically assess the ways in which we currently do things – and how unproductive we have become as a result. But what may surprise some is that an awareness of our inefficiency has been present in the public sphere for more than 60 years.

Perhaps the most critical moment in this understanding came in 1955, when British author and historian Cyril Northcote Parkinson penned a phrase in an article for The Economist that has been championed by productivity advocates ever since: “Work expands to fill the time available for its completion.” Having worked as a civil servant for the UK Government, Parkinson had witnessed the painfully slow-moving nature of bureaucracy first hand. He quickly realised that bureaucratic culture was linked with a mistaken preference for hard work over smart work – a concept he would explore further in his book, Parkinson’s Law or the Pursuit of Progress.

Parkinson’s Law suggests that if one is given more time than needed to complete a task, then said task will become more complex and time-consuming. This is simply a by-product of human nature. What’s more, the task will become more daunting and stressful.

Fortunately, there is a simple solution to this common cycle: assigning the correct amount of time for each task. Not only will this save invaluable time, but it will also reduce the complexity of the task and remove any unease that may be caused by it. Glaveski explained how Parkinson’s Law can be applied to modern-day working culture: “Shorter work days force people to become more focused [on] value creation and less inclined to schedule one-hour meetings by default, spend all day looking at emails and engage in residual work.”

Avoiding burnout

When making this introspective examination, it’s important not to focus solely on the standard eight-hour workday, since that is not where the problem ends. Indeed, it’s commonplace for both those climbing the corporate ladder and those who have already made it to the top to pull 40-plus-hour work weeks. Putting in extra time has become something of a status symbol – a representation of one’s hard work and commitment to a role. It’s a way of marking oneself out from the crowd, and has even become emblematic of success.

But this is a falsehood – a remnant of past thinking that has no place in modern society. Unnecessarily long working days don’t just make us unproductive in terms of each task we undertake; they also have more serious long-term effects. As noted by Glaveski: “Longer work days correlate with burnout and a degradation of morale, our health and personal relationships.”

Work-related stress can impact all areas of one’s life and, in effect, take it over. Consequently, one’s productivity is inevitably affected, which in turn is detrimental to the organisation one works for. Worryingly, this phenomenon is actually quite common, with ADP’s The Workforce View in Europe 2018 report showing that 18 percent of EU workers endure stress at work every day. Figures published by the UK’s Health and Safety Executive, meanwhile, show that over half of the working days lost due to ill health in the UK in the 2017/18 financial year were a result of work-related stress, anxiety or depression. As such, work-related ill health contributed to the loss of a whopping 26.8 million workdays during that period.

Time to change

Many believe that reducing the average working day from eight hours to six could make a considerable difference. Sweden has long been a proponent of this bold measure and has been experimenting with the six-hour workday for years. In 2015, for example, shorter workdays were implemented at Svartedalens retirement home in a bid to improve both the quality and efficiency of its services. Although 15 new employees were needed to make up for the shortfall in working hours – at an additional cost of €600,000 per annum – staff wellbeing and the standard of care both improved, making the trial a success.

In a sector marred by depression and exhaustion among overworked staff, the reduced hours resulted in nurses taking half the amount of sick leave as their control-group counterparts. Further, the study showed that nurses were 20 percent happier and had more energy both at work and in their free time. This in turn enabled them to carry out around 64 percent more activities with the home’s residents.

Similarly, in Gothenburg, a Toyota service centre found success when switching to a six-hour workday more than a decade ago. Prior to the implementation of a 30-hour work week, employees were generally stressed and would make frequent mistakes, leaving customers dissatisfied with the service they received. Following the change, however, the managing director of the centre, Martin Banck, told The Guardian: “Staff feel better, there is low turnover and it is easier to recruit new people.” Thanks to avoiding peak travel times, staff also benefit from shorter commutes, while machines are used more efficiently and capital costs have been lowered. Overall, profits have increased by an impressive 25 percent since the six-hour workday was implemented.

When looking at productivity data on a country-by-country basis, the evidence becomes all the more convincing. On one end of the scale is Japan, a nation notorious for having some of the longest working hours in the world. Incidentally, it also holds the title for the lowest productivity among G7 countries, according to the OECD’s Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2018.

By focusing on hours instead of outcomes, companies are not getting the most out of their talent and employees are not getting the most out of their days

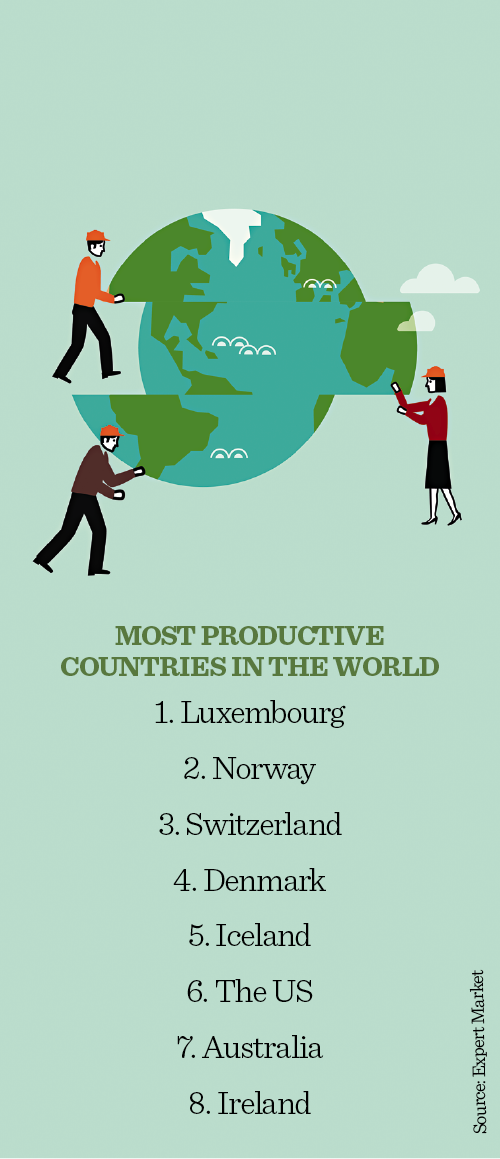

At the other end, a number of European countries – Scandinavian nations, in particular – do remarkably well when it comes to their levels of productivity. In fact, data from Expert Market shows that Luxembourg was the most productive country in the world in 2017, followed by Norway, Switzerland and Denmark. Evidently, the Scandinavian states – with their strong emphasis on wellbeing, happiness and the importance of a good work-life balance – are doing something right.

The argument in favour of shorter working days is made all the stronger when considering these countries all support a working week of between 27 and 33 hours. Luxembourgers also enjoy an average of 32 paid vacation days every year and generous wages, at a rate that translates to around $31.63 (€28.40) per hour. Parkinson’s Law offers a reasonable explanation for the country’s success: it’s simply better to work smarter rather than harder.

State of flow

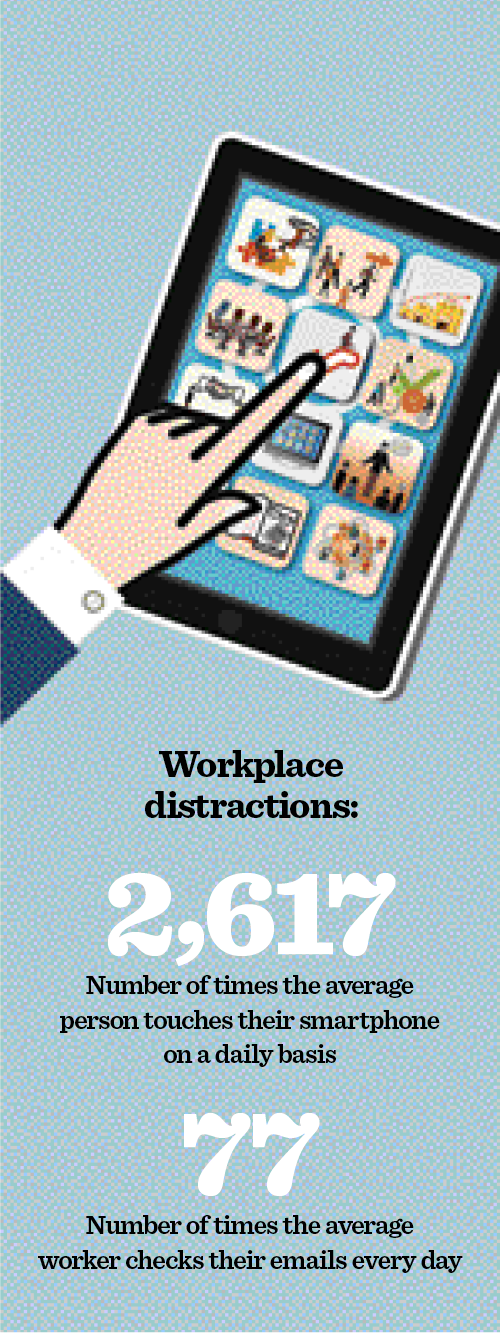

But it’s not just our unnecessarily long working hours that are denting productivity levels. Modern culture also provides a constant stream of disruptions through multiple outlets: among the worst has to be our smartphones, which have become an almost incessant form of distraction, day and night. The figures are alarming to say the least: according to Chicago-based research firm Dscout, we touch our phones a staggering 2,617 times a day. And that’s just the average person – ‘extreme’ phone users more than double this number every day.

Then there’s the frequent pinging of our email inboxes to contend with. Research undertaken by Gloria Mark, a professor of informatics at the University of California, Irvine, found that workers check their emails 77 times a day on average. Mark told European CEO: “We found that longer email duration is correlated with higher stress. We also found that the longer one is on email for that day, the lower they assess their productivity for that day.”

The problem lies in what such distractions do to our state of ‘flow’. Glaveski explained this concept in more detail: “Flow is a state of deep immersion in a single task, where the rest of the world seems to just slip away and you lose track of time. The term ‘flow’ was first coined by Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in 1975… Many today simply refer to it as ‘the zone’.”

This mental state of functioning involves full absorption, an energised focus and satisfaction in the activity. The subsequent loss of space and time is arguably when our most creative and fruitful work occurs. “A McKinsey study found that when one is in flow, they are up to five times more productive than when engaged [in] shallow level thinking,” Glaveski told European CEO.

While it has become evident that flow is necessary for optimum productivity, it is far from encouraged by today’s work environments. In fact, it’s almost actively discouraged. “It can take 23 minutes to get back into flow after an interruption,” Glaveski explained. “But if you’re checking [your] email every six minutes – not to mention your smartphone notifications and the inevitable physical interruptions one succumbs to in an open-plan office – it’s easy to see why today’s executives are spending little to no time in flow at all.”

Eliminating distractions

Despite the ubiquity of social media (which causes many of us to impulsively check various platforms for updates throughout the day), the constant pinging of emails and the distracting nature of open-plan offices, all is not lost. There are many ways in which we can prolong the state of flow and promote productivity more effectively.

Mark’s research, for example, shows that emails are a good place to start: “In a study that we did where we cut off email in a workplace for five business days, we found that people became significantly less stressed and significantly more focused. We did not directly measure productivity, although it would follow that if people were more focused, they should be more productive.” The results, therefore, suggest that leaders should encourage their teams to spend less time on their emails. As Mark told European CEO, batching emails – checking and sending all messages just two to three times a day – can “improve people’s self-assessed productivity, but only when their email volume is large”.

Glaveski agreed with this approach: “Be intentional. Turn off notifications on your phone. Batch check the things that you normally do sporadically throughout the day. When you’re working on a task that requires thinking and focus, train your brain to focus only on that task and not [to] quickly check social media. Even microtask switches that take just one tenth of a second can add up to a 40 percent productivity loss over the course of a day.”

To further encourage flow, Glaveski suggested the following: “Build momentum by just starting, rather than overthinking, and the dopamine hit… you get from making progress will motivate you to keep moving forward. You can revisit your work later and improve it if need be. If you’re not used to truly focusing for extended periods of time like this, you’ll need to train yourself to, as you would a muscle in the gym. “The thing is that our brains have evolved to conserve energy and so they trick us into thinking that the lowest-hanging fruit – like checking and responding to emails – is the ripest, when, in reality, it usually means we’re just responding to other people’s demands on our time at the expense of our own goals.”

As well as encouraging staff to turn off notifications, leaders in an organisation can create interruption-free spaces. Glaveski recommends scheduling windows of one to four hours for deep work every day and emphasised the importance of clearly differentiating between work that is urgent and work that is not. And, as always, communication is key – for example, explaining to staff the detrimental impact of frequently switching between tasks. Other tips included practising asynchronous communication, ensuring meetings do not last more than 30 minutes, and sending instant messages in place of meetings that aren’t pertinent.

Achieving optimum productivity is the holy grail for the individual, the organisation they work for and the country they live in. But it’s no easy feat: it takes a critical understanding of human nature and the ways we function and thrive. It also involves exploring general wellbeing, satisfaction in the workplace and energy levels, as well as discerning what promotes creativity and learning how to beat constant distractions. The good news is that this is achievable for anyone; the bad news is a shift in culture is never easy and taking bold moves into the unknown can take some convincing. The potential outcome, however, far outweighs any short-term sacrifice. With greater productivity, who knows what each of us can achieve and how far we can go together.