Anheuser-Busch InBev (AB InBev) was formed as the result of one major merger after another: in 1999, mid-sized Brazilian brewer Brahma acquired local rival Antarctica to form Companhia de Bebidas das Américas (AmBev).

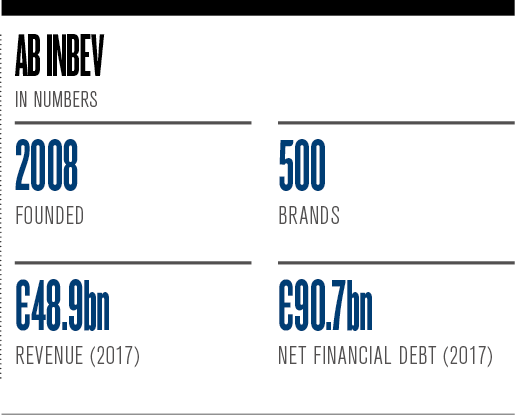

Then, in 2004, the company rebranded as InBev after it merged with the Belgian brewing giant Interbrew. Just four years later, InBev combined with US brewer and Budweiser-maker Anheuser-Busch in a $52bn (€45.3bn) deal – AB InBev, the world’s largest brewer, was born.

This did not signal the end of AB InBev’s mergers and acquisitions (M&As), though: in 2016, the Belgium-based powerhouse decided to gobble up SABMiller, the world’s second-largest brewer, in a €92bn deal that became known as ‘Megabrew’ by industry commentators.

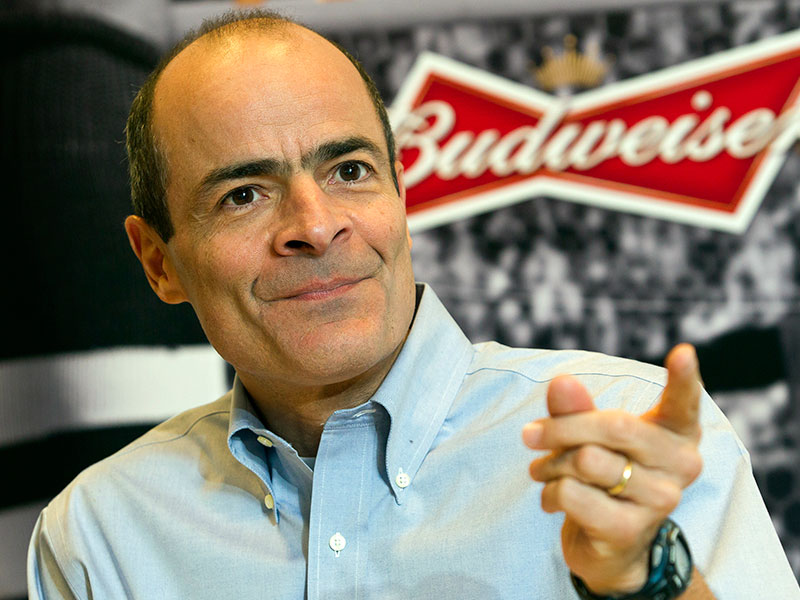

Today, AB InBev owns seven of the 10 most valuable beer brands in the world. One man has been at the centre of this flurry of market activity: CEO Carlos Brito, who started his career as an ambitious sales manager at Brahma in the late 1980s.

On the hop

Brito found his way into the drinks industry through Jorge Paulo Lemann, a partner at Brazilian investment bank Banco Garantia and the future founder of 3G Capital. At first, Lemann’s scholarship programme simply helped Brito through his education at Stanford University. But after graduating with an MBA, Brito reunited with his benefactor at Brahma, a brewer Lemann had just bought with two partners for $50m (€43.6m).

AB InBev employees are not valued on seniority, but rather on the potential they offer the company and their inherent traits

At Brahma, Brito displayed his strong business acumen, boasting a keen eye for deals and a laser-like focus. Following the 1999 merger that created AmBev, Brito quickly ascended to the top; soon after AmBev’s tie-up with Interbrew, he was named as CEO of InBev at 45 years of age.

One of Brito’s most distinctive skills is cost cutting. Following a flurry of big deals, he developed a knack for quickly trimming costs and boosting margins. Eddy Hargreaves, a consumer equities analyst at South-Africa-based asset manager Investec, said Brito’s success in taking a regional, Latin American brewer and expanding it across the globe was achieved with the help of “disciplined operational methods, such as the early adoption of zero-based budgeting to control costs tightly”.

At AB InBev, Brito has fuelled a culture of transparency, with executives sitting in central, open desks instead of in private offices. Some have likened the dynamic to that of a start-up. While Brito embodies this open management style with his choice of clothing – his typical office attire comprises jeans and a Budweiser-branded shirt – and his hands-on approach, it would be wrong to suggest he doesn’t run a tight ship.

AB InBev employees are not valued on seniority, but rather on the potential they offer the company and their inherent traits, such as curiosity and the ability to move out of one’s comfort zone. The high-pressure working environment sees young, ambitious staffers evaluated constantly; Brito makes it clear that anyone who does not meet his expectations will not remain in the company for long. In fact, according to a report by the Financial Times, outsiders have said AB InBev trainees are “brainwashed” by the company.

Devotion to the brand is non-negotiable. Brito wants everyone in the company to be as dedicated as he is – he has admitted to having no hobbies outside of the business and his family, barring a daily 30-minute run on the treadmill. In a company press release around the time of the Megabrew deal, Brito said: “People thrive in a culture based on ownership, meritocracy and informality. It’s not just a job – it has to be a passion. That is a crucial mindset. It’s also one of our selection criteria. You could compare our employees with top athletes: the dream is big, talent is scarce, selection is strict [and] sacrifices are plentiful. But all of that ultimately makes the difference.”

An unquenchable thirst

Despite his no-nonsense management style, Brito is not without charm. His warm personality has likely been an asset in his impressive track record for making deals. “Brito’s strong negotiation skills are often overlooked,” Hargreaves told European CEO. “But his ability over the years to persuade diverse owners to sell to him has been truly extraordinary.”

Through these deals, Brito has transformed the beer industry from a fragmented and disjointed market into one of consolidation, dominated by a handful of owners. According to Hargreaves, the scale of major M&A deals Brito has executed over the past 20 years is “unparalleled across the entire consumer staples industry”.

Carlos Brito has transformed the beer industry from a fragmented and disjointed market into one of consolidation, dominated by a handful of owners

Even after the tie-up with Anheuser-Busch, Brito’s thirst for expansion went unquenched. In 2011, the firm bought Chicago-based craft brewer Goose Island; a year later, the company took a majority stake in the Dominican Republic’s Cerveceria Nacional Dominicana for $1.2bn (€1.05bn). In 2013, AB InBev purchased Mexico’s Grupo Modelo for $20bn (€17.5bn).

Speaking to the Financial Times, an unnamed AB InBev advisor likened Brito and his team to sharks: “They can’t stop moving. It’s just not in their nature. M&A is in their blood.” But Megabrew was a turning point: since the announcement of the deal in 2015, AB InBev’s shares have halved from a peak of around €122.50. M&A has taken a backseat as executives focus on stabilising the business, with the $100bn-plus (€87.4bn) debt that AB InBev racked up in order to buy SABMiller starting to weigh heavily on investors’ minds.

While the deal gave AB InBev a truly global footprint with operations in nearly every important beer market, the anticipated increase in volume that was to result from SAB’s presence in the high-growth Africa region took longer to materialise than expected. At the same time, macroeconomic weaknesses in emerging markets, where 72 percent of AB InBev’s volume is sold, has heaped pressure on the company.

Trouble brewing

Last year alone, AB InBev’s share price slid almost 40 percent as it worked to put out fires on numerous fronts. The company has seen increased competition in a variety of markets, including China and South Africa. But in Hargreaves’ view, competition with like-minded rivals is “healthy” and is nothing new for Brito: “AB InBev has grown for many years in several countries where the beer market is extremely competitive.”

What is more worrying is the rising popularity of craft beer, wine and spirits: in the US market, which accounts for approximately 30 percent of AB InBev’s profits, consumer tastes have been moving from beer to wine and spirits since around 2000. In the first nine months of 2018, the company’s North American beer volume fell by three percent. Further, younger, health-conscious generations are slowly turning away from alcohol altogether.

Younger, health-conscious generations are slowly turning away from alcohol altogether

In December 2018, the Beer Purchasers’ Index – an informal metric that gives distributors an indication of purchasing activity – dropped to a measure of 47 from 55 in the previous year. At a time when more consumers are interested in craft beers, AB InBev’s portfolio skews to the weakest sub-segment in the US market: mainstream, light lager. According to Hargreaves, niche competitors like craft brewers present an “ongoing challenge” for AB InBev.

Competition could also emerge from a new area: marijuana. Some market commentators have suggested falling beer sales could be attributed to the US’ growing cannabis market. Although the number of states to have legalised recreational cannabis remains low, the industry is expected to boom in the coming years, with a 2017 report by Arcview Market Research suggesting the North American market could grow at a compound annual rate of nearly 25 percent between 2017 and 2025.

Speaking to CNBC earlier this year, Brito said his company did not have any data to suggest the growing cannabis market would hurt beer sales. In December 2018, however, AB InBev proved it was looking to get into the market itself, forging a $100m (€87.4m) joint venture with cannabis firm Tilray to study cannabis-based beverages.

The study will assess the viability of using both THC, the psychoactive chemical compound of marijuana, and CBD, the non-active chemical, in non-alcoholic drinks. According to Arcview, the North American edibles market – including drinks infused with cannabis – is expected to surpass $4.1bn (€3.6bn) by 2022.

The next round

These competitive pressures have only been exacerbated by AB InBev’s staggering debt pile. After its credit rating was cut by Moody’s in late 2018, the company began to take measures to rebalance its remaining debt – first by slashing its dividend in half, and then by refinancing $16.5bn (€14.4bn) of its debt in January 2019.

Not everyone is worried about the global brewer, however. Following these moves, RBC Capital Markets upgraded AB InBev’s stock. Speaking of the change, RBC analyst James Edwardes Jones said: “The dangers of AB InBev’s indebtedness have been overstated.” Jones also revealed he had hiked his 2019 and 2020 earnings-per-share estimates for the company, claiming AB InBev’s level of debt is “comfortably under control”.

To reduce its debt pile further, AB InBev is reportedly considering listing its Asian operations. Hargreaves said this option was likely just one of many initiatives the management team was considering, which is “consistent with its track record of creative thinking around the structure of its business”. Were such a move to materialise, Hargreaves believes it would be significant, placing a clear value on the company’s Asian operations and demonstrating the current undervaluation of the remaining business.

The Asian beer market is one of the most exciting for brewers at the moment, with volumes growing rapidly in countries such as China, India and Vietnam. Crucially, listing its Asian unit would afford AB InBev more financial flexibility, allowing it to line up new M&A deals – both in Asia and elsewhere.

In an interview with the Financial Times, Brito himself admitted that AB InBev had fallen on hard times: “There has been a change in mood among investors on emerging markets and companies that have high debt.” But he remained optimistic about the company’s future: “We continue to be very confident in our footprint, brands and our people.”

Whatever happens moving forward, Hargreaves believes Brito remains the CEO for whom he has developed the “strongest respect and greatest admiration” among all of the consumer companies he has studied over the past 25 years. “Not only are his achievements immense, but he has retained the common touch, able and willing to speak to everyone from [the] shop floor [upwards],” Hargreaves said.

Much of AB InBev’s success can be attributed to Brito and the path he has forged for the brewing giant – one that applauds curiosity and risk-taking. In place of a mission statement or a set of values, Brito often speaks about the “dream” championed by AB InBev: bringing people together for a better world. Brito’s own vision has seen AB InBev grow into the world’s biggest brewer, selling one in every four beers globally. While there are almost certainly going to be tough times ahead for the company, Brito is unlikely to see his dream falter, or his glass become half empty.