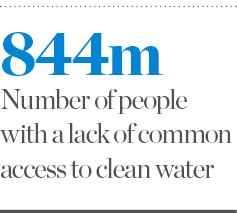

In life, we face countless challenges. Some are small – mundane even – while others are positively life threatening. In the developing world, the latter is more applicable, with a common lack of access to clean water carrying incredibly harmful repercussions for local communities. In fact, according to the World Health Organisation and UNICEF’s 2017 report Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene, some 844 million people faced this problem in 2015. The Water.org website, meanwhile, states that a child dies every two minutes from a water-related disease.

Although these figures are startling, more shocking is the fact that, while millions suffer from a lack of access to an essential human right, many of us take it for granted and pay little thought to those suffering elsewhere. Some may donate a little money here or throw a fundraiser there, but few will seek a practical solution. The same cannot be said of Solvatten founder and CEO Petra Wadström, whose company is breaking new ground with its revolutionary water-filtration technology.

The path to enlightenment

Wadström was not always on the front line of tackling one of humankind’s most pressing problems. Prior to founding Solvatten, she studied biochemical medical research at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, before moving to Basel, Switzerland, to become part of a team examining the early stages of DNA research. Wadström also explored less scientific pursuits, following in the footsteps of her mother and sisters – all of whom are artists – by studying art in the evenings.

The seminal moment of Wadström’s career, however, would come when she moved to Australia for a year with her husband and four children. While her husband worked in a hospital, Wadström took the opportunity to explore her artwork further and began making prints at an art shop in Sydney. It was during this time that she started working with Aboriginal women, teaching them the art of printmaking. “I met quite a lot of [Aboriginal women] who were really struggling with life – with an unhealthy family and unhealthy children,” Wadström said.

While in Australia, Wadström was taken aback by one of the country’s most abundant resources: “I was surprised when I saw the amount of solar energy and sunshine, and that it was not really being used.” And so, Wadström started to wonder if the two could be combined in order to resolve some of the problems facing so many women around the globe. “I was convinced to continue when I was in Indonesia and I met women who were struggling with their lives,” Wadström said. “I could see then [that] unhealthy water was the biggest problem, causing a lot of poverty and illness.”

Upon returning to Sweden, Wadström continued to ponder the daily problems she had encountered during her travels: “I thought, ‘Who is going to help to solve this problem? Or at least do something about the problem?’ I was thinking, ‘Why wait for someone else to do it? What can I do?’” And herein lies the difference between Wadström and most other people – she decided to take the matter into her own hands.

Wadström imagined a portable device that could use the abundance of sunshine in developing nations to both clean and heat dirty water. The possibilities of such a tool were myriad: not only could it be used to provide drinking water to the countless individuals who normally have to walk for hours each day for such a basic human need – it could also be used for cooking. Add to that hot water’s ability to create a more hygienic home environment, and it’s clear to see the invaluable benefits such a device would provide.

With this in mind, Wadström started creating prototypes at home and testing them using her own equipment. She then began visiting local water treatment plants to carry out further tests. “I wanted to see if we could add a lot of bacteria into the water – they found it was totally clean after exposure to the sun,” Wadström told European CEO. “So that was the start. And then I couldn’t just sit [still]… I couldn’t stop.”

Pure intentions

Solar energy’s proficiency in cleaning contaminated water has long been documented. According to Solvatten’s website, it works because “ultraviolet light destroys the formation of DNA linkages in microorganisms, thereby preventing them from reproducing and thus rendering them harmless”. Wadström’s invention, which opens up like a book to make the most of available sunlight, also heats water up to 75 degrees Celsius – the temperature at which pathogens are inactivated.

In around two to six hours, the water contained within Solvatten is free of pathogenic materials. Users know when the process is complete as a sad, red face turns into a happy, green one. Once purified, the water becomes drinkable and can be used either hot or cold. Obviously, sunlight is key to the effectiveness of the device: while it can be used on days that are partly overcast, it cannot be used when there is thick cloud cover or heavy rain.

Solvatten’s impact has been considerable, especially among those who are most susceptible to waterborne diseases

Having done enough to convince UN-Habitat in Nairobi to provide start-up capital, Wadström turned her attention to further research, travelling to Nepal to test the efficiency of Solvatten at different altitudes. She also took the time to speak to women on the ground, asking them about the problems they faced on a daily basis and how Solvatten might help tackle them. “I think it was a very important start, to be close to the users, to the beneficiaries,” Wadström told European CEO.

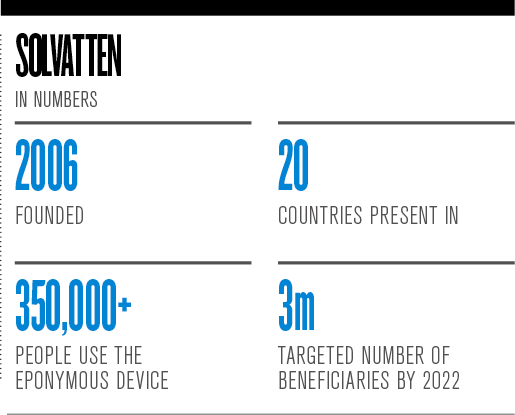

Wadström started her company, which shares its name with the device she invented, in 2006. Further investment shortly followed, and Wadström was quickly able to push the project forward. “I was lucky to find a business angel, a woman who really helped out financially, but also as a mentor,” Wadström said. “I had someone to discuss [things] with, and I think that was one of the most important parts… The early stage was the most problematic and it was, of course, very expensive to invest in the tools needed to manufacture Solvatten.”

Helping hand

Today, around 350,000 people across 20 countries use Solvatten. Its impact has been considerable, especially among those who are most susceptible to waterborne diseases – namely, children under the age of five. This is thanks to the tool’s lifespan, which ranges between seven and 10 years, ensuring children are protected while at their most vulnerable.

A 2011 study conducted by students at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences shows just how much has been gained from the use of the technology in Bungoma County, Kenya. The social return on investment ratio was calculated as 1:26, meaning that for every $1 (€0.90) invested in Solvatten, a value of $26 (€23.32) was created.

This exceptional outcome is attributed to several benefits that result from Solvatten, including the improvement of health in women and children, and the inordinate amount of time saved collecting water and firewood. According to the report, a typical family in the district was sick 4.3 times per month on average prior to the implementation of Solvatten. After the device’s introduction, this figure dropped to just 0.03 times a month.

“This effect was calculated to result in a gain of 20 hours per household per month from not being sick,” the report read. Households also saved around $24 (€21.53) on medicine and medical services per month, while this improvement in health resulted in higher attendance at school: prior to the introduction of the technology, the recorded rate of irregular attendance was around 67 percent. After purchasing Solvatten, however, the school’s overall attendance increased by an impressive 87 percent.

The time saved was also a significant boon for each family and the community as a whole. Instead of spending hours collecting firewood or buying fuel in order to boil and purify water, this time was spent engaging in income-generating activities. “It’s really important for us to highlight those impacts,” Wadström said. “Return on investment is not enough – you need to have the social return on investment as well to make the whole thing [viable].”

There are environmental benefits to using Solvatten, too. Due to a lack of energy infrastructure in remote, poverty-stricken areas, individuals rely on resources such as charcoal and wood for cooking and washing. Indeed, according to Solvatten’s website, around 70 percent of the energy used in a typical home in sub-Saharan Africa is consumed for this purpose. As stated on the website: “This strong dependence on natural resources [leads] to smoke inhalation, burn injuries, carbon dioxide emissions and deforestation, which give rise to environmental problems.” Solvatten abolishes these issues by utilising a renewable, abundant energy source that has no toxic by-products.

Bright future

Despite the advantages and conveniences that many of us enjoy today, there are still millions of people without access to safe water – a fundamental building block of healthy living. It’s estimated that one in eight people suffer from this problem and, given the number of deaths caused by diarrhoea and other water-related illnesses, this issue must be at the forefront of our efforts to make the world a better place. “We see too many people living in poverty and without access to safe and hot water,” Wadström said. “And so, for us, [our goal] is to reach the most vulnerable people.” In fact, Wadström plans to reach three million people within the next three years – a goal she says is feasible as awareness grows and support follows.

Despite the advantages and conveniences that many of us enjoy today, there are still millions of people without access to safe water

At present, Solvatten is largely distributed through private companies making donations as a part of their corporate social responsibility programmes, but governments in the developing world are beginning to take notice.

This will be key to the widespread adoption of the technology and to putting it in the hands of those who need it most. Seeing the positive effects Solvatten has had on so many lives keeps Wadström driving forward with her mission. “To see that it’s become a solution for so many people, that has helped me very much to overcome some hurdles and challenges on the way,” she explained. “I think the best reward is to see the impact Solvatten has for the users.”

When asked what advice she has for aspiring inventors and entrepreneurs, Wadström said: “Be very clear from the beginning what the problem you want to solve is, and for whom… Is it someone who is going to use your solution? I think it’s good to think about that very early [on]. We have to be very aware of what we create – it has to be useful.” Wadström added that it’s important “to be kind to yourself” and recognise what you have achieved each step of the way.

By doing so, Wadström has created something that truly makes a difference in people’s lives. Through easy access to clean, hot water, individuals are afforded life’s two most precious gifts: health and time. This drastically improves their way of life, giving them the opportunity to study, work and do what matters most to them. Solvatten is an inspiration, as is its inventor. Indeed, Wadström is testament to what can be achieved when one takes matters into one’s own hands, and how each of us can make the world a better place.