“Who is François-Henri Pinault?” was the question countless tabloids were asking in April when Pinault announced his family would give €100m to the reconstruction of Paris’ Notre-Dame Cathedral after it was devastated by a fire. The pledge not only kicked off a round of donations from the upper echelons of France’s business elite, but it also sparked public interest in Pinault himself, with Google searches of his name suddenly spiking to their highest level in more than 10 years.

In certain circles, Pinault is better known for being the billionaire husband of actor Salma Hayek than the CEO of luxury goods giant Kering. While his name may not be familiar outside of France or the fashion industry, the names of the dozens of luxury brands he operates, such as Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent, certainly are.

Luxury fashion is often framed as an indulgence, but in France it is woven into the country’s economic health. According to government figures, fashion contributes 2.7 percent of GDP. The sector generates €150bn in direct turnover and employs one million people, and over the past few years, the growth of Kering and its rival LVMH has only intertwined the sector further with France’s success. As Invest Securities analyst Christian Guyot told Bloomberg, luxury fashion brands have “reshaped” France’s CAC 40 stock index.

Shifting focus

In spite of major changes to the luxury goods industry – from the emergence of e-commerce to faltering consumption in China, which is responsible for a third of global luxury spending – the market is thriving. Deloitte’s Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2019 report found that sales at the world’s top 100 luxury goods firms grew nearly 11 percent in the 2017/18 financial year.

Pinault decided to divest from everything except the luxury goods assets Kering (then PPR) had gained from the 1999 acquisition of Gucci Group

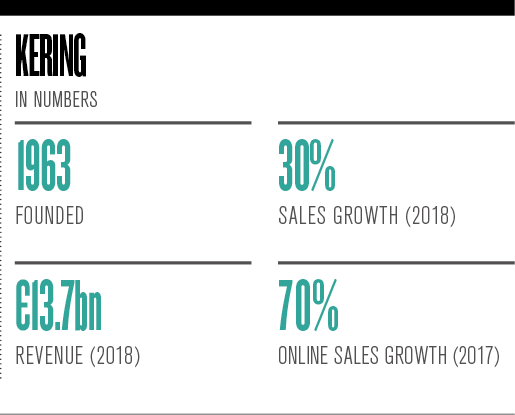

Change is nothing new for Kering, the world’s fourth-largest luxury goods group, with a value of around €66bn. Pinault’s father, François, founded the company in 1963 as a lumber business called Pinault Distributions. It was not until the 1990s that retail became a core part of the business, when it purchased French department store chain Printemps in 1992 and the mail-order catalogue firm La Redoute in 1994. Following this, the company was renamed Pinault-Printemps-Redoute (PPR).

As his father built up the business, Pinault was working his way up the company as a manager in PPR’s buying department. Pinault joined the family business in 1987 after beginning his career in the tech sector, first working as an intern for Hewlett-Packard in Paris and then helping to create the start-up Soft Computing in 1985 with classmates from HEC Paris. Later, he also worked as CEO of PPR-owned electronics chain Fnac.

As soon as it was announced that Pinault would succeed his father as CEO and chairman of PPR in 2005, he began to push through radical changes in the company. Writing for Harvard Business Review in 2014, Pinault said he was faced with a decision: “Should I leave things the way they’d been under my father, or should I take them in a new direction?” Pinault described PPR’s businesses at that time as an “eclectic” mix – including everything from department stores to building materials companies. He subsequently decided to divest from everything except the luxury goods assets the firm had gained from the 1999 acquisition of Gucci Group.

But as Pinault aimed to narrow the company’s focus to luxury goods, he also made a plan to expand PPR’s reach by focusing more on international markets, prompted by concerns that the company was tied too closely to France. Pinault wrote at the time: “The company needed to become more international, more growth-orientated, more profitable.”

By 2013, when the company was renamed Kering – a play on the English word ‘caring’, and a reference to the Pinault family’s roots in Brittany, where ker means ‘home’ – Pinault had sold off assets including Printemps, La Redoute and Fnac, and acquired more luxury brands, such as Swiss watchmaker Girard-Perregaux and Italian menswear couture house Brioni.

Although these deals significantly reduced the company’s size, Kering had found its niche: according to Pinault, sales from 2003 to 2014 more than halved from €24.4bn to €9.7bn, but profits shot up by around 40 percent. The share of the company’s revenue from France dropped from 41 percent in 2007 to four percent in 2014.

Alessandro Brun, the director of MIP Politecnico di Milano’s master’s course in global luxury management, told European CEO that Kering’s strategy of divesting non-core brands had paid off, as it allowed the company to adjust to market changes with agility while producing strong organic growth. “Steady, sustainable and profitable growth is, simply put, the holy grail of financial success in a corporation,” Brun said.

A new lease of life

Following this dramatic shift in Kering’s portfolio, Pinault became focused on generating organic growth at the company’s labels. He has since found great success in revamping some of the firm’s less profitable businesses – for instance, Yves Saint Laurent’s sales have tripled since 2013, when Pinault appointed Francesca Bellettini as the label’s CEO. The firm is now the second-largest in Kering’s portfolio.

The 100-year-old brand Balenciaga has also seen a surge of growth thanks to its soaring popularity with Millennials, who account for around 60 percent of sales. With its new streetwear-inspired look, Balenciaga was Kering’s fastest-growing brand in 2018. Brun expects the label’s strong growth to continue, saying Balenciaga “has the potential to… explode”. He added: “I predict that Balenciaga and Saint Laurent could be the new Bottega Veneta and Gucci. They just need the right people and the ability to interpret the most current cultural trends and exploit them.”

Pinault has made it a priority to match up winning sets of CEOs and creative directors, writing in Harvard Business Review that getting this pairing right “keeps the strategic vision and the creative vision aligned”. At Gucci, for example, CEO Marco Bizzarri and creative director Alessandro Michele both joined in 2015 and have had enormous success in overhauling the brand together.

Gucci, Kering’s crown jewel, is now one of the fastest-growing brands in the world, according to consultancy firm Interbrand. By the end of 2018, sales surpassed €8bn after rising nearly 37 percent. Pinault is targeting €10bn in annual sales for Gucci, which would knock aside LVMH’s Louis Vuitton to make it the world’s top luxury brand. But Pinault’s smart staffing decisions are not the only reason so many of Kering’s brands are flourishing. “Such a streak of successful turnarounds cannot be explained [by] focusing on just one key ingredient… Rather, it required the alignment of many factors,” Brun said.

Although the luxury industry long resisted e-commerce, convenience is beginning to win out over convention

Another important facet of Pinault’s strategy is giving each brand a degree of relative autonomy within Kering’s overarching aims. A label’s creative director is not only in control of the brand’s products, for example, but also the brand image, the store concepts and advertising. With such a high level of independence and trust, Brun said brands are allowed – even incentivised – to experiment. “Some experiments might fail, but they are making the group stronger,” he said.

While brands are encouraged to establish their own identities, they also have the all-important backing of Kering when it comes to supply chains, marketing budgets, IT and other less glamorous aspects of the industry. This “parenting effect”, as Brun calls it, can make a big difference to smaller brands. Pinault stressed the significance of this relationship in Harvard Business Review, writing: “People tend to focus on the deal-making, but how we help our brands grow organically and benefit from their collective experience is the most important aspect of what we do.”

Luxury in the digital age

Although the luxury industry long resisted e-commerce, convenience is beginning to win out over convention. However, newfound awareness of the importance of online shopping does not mean luxury brands can ignore the in-store experience. “The evolution of e-commerce has created a demanding luxury consumer who looks for extra experiences and retail services,” Fflur Roberts, a research analyst at Euromonitor International, told European CEO. “‘Retailtainment’ is a term used to refer to the incorporation of these services and experiences into [brick-and-mortar] outlets.”

In Brun’s view, Kering has so far shown an “outstanding ability” to manage the tricky balance of upholding tradition while pursuing innovation. The brand addressed the rising significance of online shopping with a redesign of its website in 2016 and the addition of online stores in key markets, such as China and the Middle East. In 2017, Gucci’s e-commerce sales rose by 86 percent, according to Deloitte. But Gucci has also worked to keep its brick-and-mortar shops relevant with marketing campaigns that included transforming its flagship stores into interactive art galleries or spaces that feature augmented virtual reality experiences.

E-commerce is crucial for the luxury industry, and Pinault, with his background in technology, has long understood that. In 2015, he stressed the importance of matching up the experiences of online and in-store shopping, telling The Wall Street Journal: “If what you do online is perceived to be not as luxurious as what you do offline, you have a problem.” Further digital advances may be available to Kering in the near future as the company brings its online operations in house from 2020, following the conclusion of a 2012 joint venture in e-commerce with Yoox Net-a-Porter.

Wearing on the environment

Another aspect of the modern luxury consumer’s evolution is a growing concern over sustainability. The sector is responsible for around 10 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions and 20 percent of global wastewater production, according to the United Nations. “Discerning consumers are increasingly demanding transparency and consistency, seeking out responsibly sourced, manufactured and distributed products,” Roberts said.

In many ways, Kering has been a trailblazer for sustainability in the fashion industry. By 2025, the company aims to cut its carbon emissions in half and for 100 percent of its suppliers to meet its standards on environmental stewardship, traceability, animal welfare, working conditions and use of chemical products. The brand’s identity has long been imbued with sustainability: the firm was one of the first to implement a code of ethics and a sustainability team, established in 1996 and 2003 respectively.

Since Pinault became CEO, Kering has taken more radical steps, including the development of its environmental profit and loss methodology in 2011. This tool measures the financial cost of the company’s business activities on the environment. In 2017, Kering said it was on track to reduce environmental profit and loss by 40 percent across its supply chain by 2025. Kering’s pioneering work in this area has earned it the title of the second-most-sustainable company in the world in Corporate Knight’s 2019 Global 100 ranking.

Pinault’s vision for sustainability is likely born out of his focus on long-term thinking. In a 2012 interview with TechCrunch, he said he knew from day one of becoming the CEO of PPR that he would transform Kering into what it is today: “I already had a strategy in mind, and I started implementing that strategy for the long term, step by step… Since then, we have been moving forward with no rush, but with the objective clearly in mind.”

Over the last decade and a half, Pinault has worked to reshape Kering into a steadily growing pillar of strength in the luxury market by reviving struggling brands, developing a niche in which to operate and expanding the company’s international reach. Along the way, Pinault has helped to redesign France’s luxury market, positioning fashion as one of the country’s leading economic drivers. While luxury fashion has been, and always will be, deeply ingrained in French culture, its relevance today is stronger than ever.