The world is getting richer. Despite a temporary €2trn setback during the global financial crisis, the wealth of the richest people in the world – the ultra-high-net-worth individuals (UHNWIs) – has risen steadily over the years.

No other segment of the wealth pyramid has been transformed as much in the years since 2000, according to Credit Suisse’s 2017 Global Wealth Report. In that time, the number of UHNWIs – or those with a net worth of $50m (€42.9m) or more – has risen five-fold.

The speed of this growth is accelerating, too. In 2017, a report by property consultancy Knight Frank and wealth research firm Wealth-X described a 10 percent rise in the global number of UHNWIs as a “notably more rapid rate of growth than [recorded] in the previous five years”.

The US is famous for pumping out billionaires, and for good reason: seven of the top 10 billionaires on Bloomberg’s Billionaires Index call the US home. But the picture is changing, and one area in particular continues to fly under the radar: Eastern Europe. Wealth is growing in this region, while a burgeoning culture of entrepreneurialism is fostering the potential for a boom in its ultra-rich population.

Climbing the ranks

According to a 2016 report by Deloitte, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) is on track to become a significant contributor to Europe’s UHNWI wealth. Deloitte described UHNWIs as those with over $10m (€8.6m) in assets, while its definition of Eastern Europe included Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Russia.

From 2016 to 2021, Deloitte said the ultra-wealthy segment of CEE would grow at a rate of 7.6 percent, adding €400bn to European wealth over the five-year period. This figure would match the combined contribution expected from Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

A burgeoning culture of entrepreneurialism is fostering the potential for a boom in Eastern Europe’s ultra-high-net-worth population

Boston Consulting Group (BCG), meanwhile, had a wider definition of Eastern Europe. In its Global Wealth 2018 report, which included the contributions of Croatia, Estonia and Latvia, BCG found wealth in Eastern Europe rose by 18 percent to €3.3trn last year, boosted by the strengthening of local currencies against the dollar. Across the region, BCG expects a compound annual growth rate of 11 percent over the next five years.

Eastern Europe and Central Asia showed the greatest concentration of wealth at the top; in 2017, billionaires alone held almost a quarter of investable assets in the regions. According to Bloomberg’s Billionaires Index, 28 Eastern Europeans had a combined net worth of $294bn (€252bn) in June, a figure that had risen by $3.4bn (€2.9bn) over the first half of the year.

Entrepreneurial spirit

There is no question that the number of ultra-rich Eastern Europeans is on the rise, but the driving force behind this trend is less obvious. In his new book The Wealth Elite, German academic, author and investor Dr Rainer Zitelmann interviewed 45 German citizens whose wealth ranged from €10m to as much as several billion euros to determine how the ultra-rich created their wealth.

Zitelmann also sought to identify the personality traits and behaviour patterns behind the individuals’ financial success. One statistic in his research was particularly striking; Zitelmann found 60 percent of the interviewees’ parents were self-employed, a figure that is 10 times higher than in the German population at large.

The parents of UHNWIs were frequently entrepreneurs, small-business owners or farmers. Although they were not necessarily rich, they taught their children it was not necessary to answer to an employer to make a living. Zitelmann said: “It was something of a foregone conclusion for these interviewees when they were children and young people that they would later go into business for themselves.”

Many of them did, eschewing the typical jobs associated with one’s formative years – such as working behind a bar or through a temp agency – in favour of following their own ambitions. Examples of such entrepreneurial spirit included setting up a bicycle repair shop, selling handbags door to door and founding a film club. One interviewee even traded stocks from a bedroom in his parents’ house, earning €40,000 in just six months.

“A look at their varied ideas and initiatives reveals a tremendous amount of creativity,” Zitelmann said. “There can be no doubt that these experiences shaped the young people who would later become entrepreneurs. They learned to organise, to sell [and] to think like entrepreneurs. They learned – often unconsciously – and acquired the implicit knowledge that is of such great importance for any entrepreneur or investor.”

Zitelmann believes there is a clear correlation between someone’s personality and how likely it is they will become rich: “It’s very unlikely to become super-rich as an employee. Sure, there are some CEOs who earn a lot, but I would guess more than 90 percent of the super-rich became super-rich as entrepreneurs.”

If a spirit of entrepreneurialism is the most important factor in becoming an UHNWI, it’s no surprise Eastern Europe is home to a growing number of them.

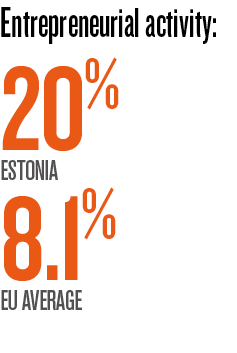

The latest Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) revealed that Estonia’s economy registered some of the highest ratings across the report’s entrepreneurial framework conditions. In Estonia, 18 percent of adults planned to start a business within the next three years. Moreover, nearly one in five adults were involved in early-stage entrepreneurial activity, compared with the European average of 8.1 percent.

According to the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) latest report on entrepreneurship in Europe, Estonia’s entrepreneurial success is no accident: the Estonian Government purposefully initiated a set of reforms that turned an existing system of state-owned companies, guaranteed product markets and fixed prices upside down in the 1990s.

“Estonia’s government has continued to innovate, most visibly with the digitalisation of government services, an area where Estonia has a global lead,” the WEF report read. “Estonia now offers e-residency to anyone in the world who would like to do business online from a virtual base.”

What’s more, the World Bank has rated Estonia as the 14th-best place to start a business, and the country was ranked 12th in the organisation’s survey on the ease of doing business. A number of well-known tech ventures started in Estonia, including two unicorns: video-chatting platform Skype and low-cost money exchange app Transferwise. Starship Technologies, a popular self-driving robot delivery start-up, was also founded in Estonia.

Meanwhile, Poland ranked fourth on GEM’s Entrepreneurial Spirit Index, which measured awareness, opportunity perception and self-efficacy – the belief someone has in their innate ability to achieve their goals. In Poland, more than half of adults believe they have the required skills and knowledge to start a business, while almost 70 percent said they saw good opportunities in the area where they live. Further, nearly 10 percent plan to start a business within the next three years.

Attitudes towards entrepreneurship have changed in Estonia over the past five years, and potential business-owners are beginning to fear failure less

Poland also took third place in HackerRank’s list of countries with the best developers, finishing well above the US in 28th. Also featured in the top 10 were Hungary, where unicorn software start-ups Prezi and LogMeIn were created, and the Czech Republic, which is home to CEE’s oldest unicorn, Avast.

Listen to your gut

Nicos Nicolaou, a professor at Warwick Business School who has studied the ‘entrepreneurial trait’ for a number of years, estimates the characteristics an individual is born with account for approximately 30 to 35 percent of their capabilities as an entrepreneur. The remaining percentage is dependent on the environment an individual is in and whether they make the most of any available entrepreneurial opportunities.

While Zitelmann stressed the significance of seeing a parent achieve success as an entrepreneur, he also believes the importance of role models outside the home should not be underestimated: “The rich parents of friends, wealthy relatives, classmates at boarding school and affluent neighbours impressed a number of these future UHNWIs with their lifestyles.”

Tea Danilov, Head of the Foresight Centre, a think tank set up by Estonia’s parliament, echoed this sentiment, saying a personal example – such as personally knowing an entrepreneur – was a “crucial motivation” to starting a business. According to Danilov, Estonian attitudes towards entrepreneurship have changed over the past five years, and potential business-owners are beginning to fear failure less.

Danilov explained that this change was characterised by indicators such as “seeing entrepreneurship as a successful career choice, the high status of entrepreneurs in society, and the high media attention to entrepreneurship”.

Personality traits also play a role in determining whether an individual is capable of attaining ultra-wealthy status. In his research, Zitelmann confirmed the hypothesis that entrepreneurs are extremely optimistic, though the UHNWIs’ definition of optimism was more in line with self-efficacy. He said: “For them, optimism is self-confidence in one’s own actions, as well as one’s own organisational capabilities and problem-solving competence.”

This high level of optimism, or self-efficacy, leads to a higher level of risk propensity, meaning the person is more willing to swim against the current and break the rules – two important qualities for creating and maintaining wealth. Other prominent personality traits included conscientiousness – or being careful and vigilant – extroversion and openness. UHNWIs were also good at dealing with setbacks, tending to move on from negative experiences quickly by taking personal responsibility and then forgiving themselves.

Zitelmann also confirmed most UHNWIs do, indeed, listen to their gut feelings when making important decisions. He believes gut feelings are not a “mystical property”, but rather “the expression of implicit knowledge – the outward representation of implicit learning”. Only one of Zitelmann’s interviewees said gut feeling had no bearing whatsoever on his decision-making behaviour.

Russian recession

The future growth of Eastern European wealth could be put at risk by Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which includes nine former Soviet Republics, such as Azerbaijan, Belarus and Kazakhstan. These countries are not always included in measures of Eastern European wealth but, when they are, they offer a considerable boost. At 2,870, the number of ultra-wealthy individuals living in Russia and the CIS accounts for around two percent of the global total.

In Russia, however, much of the wealth of ultra-rich individuals relies on the oil and gas industry. Speaking to European CEO, Liam Bailey, Partner and Global Head of Research at Knight Frank, said UHNWI wealth has declined in recent years due to the weakening price of oil and sanctions by the US and the EU.

Despite this, the region bounced back in 2017, with the number of UHNWIs in Russia growing by 25 percent – a trend that coincided with the country’s exit from recession at the start of the year. However, the number of UHNWIs in Russia was still 37 percent lower than at the start of 2012, according to Knight Frank.

“I think the fact that there’s been an improvement there comes down to a rebound in terms of the economy,” Bailey said. “It hasn’t been growing that strongly, but certainly compared to recent years it’s been pretty healthy.”

Zitelmann expects fewer UHNWIs to come out of Russia in the future, as the region demonstrates a lack of entrepreneurial spirit: “It’s totally different from the wealthy people in the US. Where are the inventions from Russia? There are none. The people who became rich in Russia became rich in a very different way.”

Bailey was more optimistic: “Ultimately, it all comes down to the performance of the economy – the ability of the Russian economy to generate economic growth and wealth creation. But I think there’s a certain expectation it will continue.”

An uncertain future

According to a recent report by UBS and PwC, the current up-cycle of wealth creation will likely come to an end in the next decade or two. Over the past 10 years, the ultra-rich have done particularly well because the prices of financial assets have swelled.

Anthony Shorrocks, a director at Global Economic Perspectives and co-author of Credit Suisse’s wealth report, told European CEO: “In the last year or so, [growth is] not quite as apparent. Maybe they won’t do quite as well in the future. As interest rates go up, asset prices are not going to go up. They may even go down, and that’s going to have an impact.”

Personality traits play a role in determining whether an individual is capable of attaining ultra-wealthy status

Vincent White, Managing Director at the Wealth-X Institute, appeared to disagree, stating in a report that although the ultra-rich segment will face geopolitical headwinds, including monetary tightening, the population is expected to continue to grow in the medium term: “Even when conditions are negative, we have traditionally seen more resilience among ultra-wealthy populations.”

Despite this, White also cautioned that societal changes could shift the picture over the longer term: “The reaction to wealth inequality is a pressure that shouldn’t be ignored. There may well be a point where the growth in ultra-wealthy populations doesn’t automatically continue on its current trajectory.”

Zitelmann was sceptical about theories calling time on the growth of wealth creation. “Big fortunes are the result of new inventions,” he told European CEO.

“The theory that the up-cycle will end would mean the time of inventions is over.” Zitelmann expects many more billionaires to come out of China, so long as the country continues on its current pathway towards capitalism, but he expects a decline in areas where entrepreneurial spirit and innovation lag, such as Russia and some other parts of Europe.

Looking at Eastern Europe, Bailey expects future economic growth to continue to outpace the EU average: “There are lots of challenges to that, but I think the expectation is that the pattern will continue for the next few years. There is ample opportunity for wealth creation within those economies.”

Research into the wealth of Eastern Europeans is still in its infancy, however. Zitelmann said he has “a lot of doubts” about the collection of global wealth research that is currently available: “You use them, I use them, because there’s nothing else, but this is the only reason. I wouldn’t call them scientific studies.”

Shorrocks, who has worked on wealth research for 50 years, warned that, while researchers make their best efforts and estimations, there are still “lots of little question marks in the analysis”. A growing number of countries are starting to produce better data, meaning more precise insights could be on the horizon.

As for now, Zitelmann hopes his research will pave the way for further scholarly studies into the mysteries shrouding the world’s wealthiest people: “After all, this book is only a first step towards understanding the wealth elite.”