Change may be difficult, but inertia can prove truly damaging, particularly from a business point of view. In the corporate world, standing still is the same as going backwards. However, once a market has become saturated, businesses have little choice but to enter new verticals if they want to pursue further growth.

Fortunately, if businesses do choose to diversify, there are plenty of positive examples to follow. Not so long ago, Xerox was so synonymous with its core industry that it became common office parlance to ask for ‘a Xerox’ of a document, rather than a photocopy. Today, however, Xerox is a $10bn (€8.5bn) global company that is just as likely to offer consultation and training services as it is office technology. Similarly, the UK-based Virgin Group has successfully ventured into a host of different industries, from transport to entertainment.

However, many less successful examples of diversification have quickly faded from memory: Coco-Cola began an ill-fated wine business in 1977; Kodak’s foray into pharmaceuticals lasted just six years; and the less said about Cosmopolitan’s range of yoghurts, the better. It is easy to understand why a new industry, with its potential new customers, might prove attractive to a business, but diversification should never be viewed as a quick or easy way to further growth.

It’s all relative

In September, within the space of just 48 hours, two high-profile firms both announced unexpected pivots. First, Dyson declared it would be entering the electric vehicle market, stating it would have a car that was “radically different” from its competitors ready by 2020. Then, Swedish furniture firm IKEA revealed its intention to enter the gig economy through its acquisition of the on-demand services platform TaskRabbit. These two different diversification efforts have provoked two very different reactions from industry experts.

With no chassis or production plant, it’s been argued that Dyson’s time frame simply isn’t viable, particularly when safety regulations across various markets are also considered. The electric vehicle space is also highly competitive, with established car firms like Volkswagen (VW) and Silicon Valley tech companies like Tesla all having a head start on the UK firm. Dyson will be diversifying into a potential growth area, but one that it will not have all to itself.

The difficulty of diversifying lies in predicting which industries can add value to your business and which ones will simply exacerbate your problems

IKEA, on the other hand, was largely praised for its acquisition, with many believing its decision to enter the services trade was a natural extension of its furniture selling business. As Andrew Shipilov, Professor of Strategy at the INSEAD business school, explained, the differing reaction to Dyson and IKEA’s respective moves stems from a subtle, but important, distinction.

“There are actually two kinds of diversification: related and unrelated,” Shipilov said. “The latter involves businesses entering markets in which they have no related resources. However, the more that businesses move away from their core competencies, the greater the chance of problems emerging.”

In the case of IKEA and Dyson, the former has simply chosen to broaden its existing ecosystem. TaskRabbit’s technology and knowledge will allow IKEA to offer furniture-building as a service alongside the products it sells in its physical stores. For Dyson, however, its diversification is much more of a leap in the dark.

It is also worth keeping in mind that as diversification extends further away from a company’s core offering, it is easy for costs to swell. Tesla has received investment of $10bn (€8.5bn) since 2012, while VW has earmarked $84bn (€71.7bn) to spend on its own electric vehicle technology over the next 12 years. Currently, Dyson’s proposal has set aside just $2.7bn (€2.3bn). In the past, the company has successfully broadened its product range from vacuum cleaners to hand dryers and beyond, but building a car could prove a stretch too far.

A survival strategy

Although in many cases diversification can simply act as a way of building on existing success, at other times it has proven imperative to a company’s survival. Consumer trends can change drastically; new technologies can spring out of nowhere to overhaul entire industries. The most resilient firms are those that can foresee these changes and embrace them before their core offering becomes obsolete.

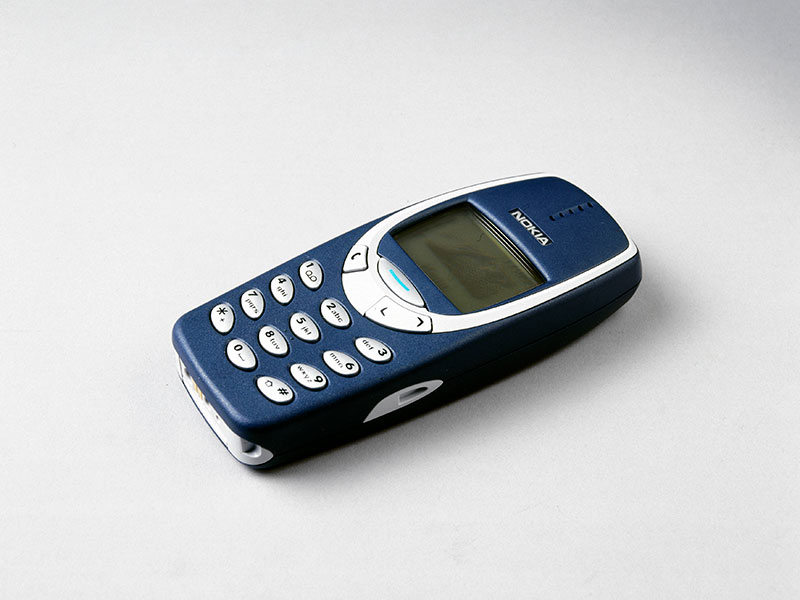

Finnish firm Nokia began life in the 1860s as a paper manufacturer, for example. But, upon seeing the growth of various new technologies, the company eventually entered the telecoms space, becoming the world’s best-selling mobile phone brand by the late 1990s. However, as the industry developed, Nokia was unable to shift its focus to software, eventually falling behind smartphone developers like Apple as a result. Ironically, Nokia was able to successfully diversify into unrelated industries throughout the 20th century, but the rapid growth of the app economy caught the company by surprise.

Industries naturally go through peaks and troughs, while some simply become outdated as new technologies appear and markets shift. Diversification, therefore, can provide organisations with a way of moving from a failing core industry to one of emerging growth. The difficulty lies in predicting which industries can add value to your business and which ones will simply exacerbate your problems.

Size isn’t everything

Although the success stories of huge global conglomerates may make diversification a tempting growth proposition, it is not the only way for businesses to enter untapped markets. Shipilov argues collaborating with firms that are already present in your prospective industry is a less risky approach: “Diversification for its own sake is dangerous, but if you specialise and partner then you can get pretty much the same benefits and be much more flexible than you otherwise could have been.”

For many organisations, even those with huge financial and technological scale, partnerships represent the go-to method of entering new verticals. MasterCard, for example, has partnered with Parkeon to turn traditional parking meters into connected devices. Despite global revenues in excess of $10bn (€8.5bn), MasterCard didn’t enter the smart city sector on its own. Instead, the company combined its payments processing technology with Parkeon’s resources in the parking and transportation space to deliver a solution that makes the most of both organisations’ assets.

What’s more, it’s important for business leaders and investors to not get lured in by size alone. Revenue growth for Europe’s 10 largest conglomerates averages approximately 1.5 percent when viewed across 2016/17, far below that of the continent’s fastest-growing firms. Of course, it’s easier to grow a start-up than an industry behemoth, but even factoring in size differences, the economic benefits of conglomerates have looked shaky for some time.

More focused companies are often easier to manage and possess a clear, strategic goal – something that can be lacking with diversified firms. “One of the main reasons that diversification fails is because businesses do not have the right strategy in place,” Shipilov said. “They must think carefully about what distinct resources or capabilities they can move between different markets to give them a competitive advantage. Too often, businesses think that financial clout will be enough, but money is not a unique resource.”

From an investment point of view, diversified firms also have their issues. A McKinsey & Company report, for example, found that median total returns to shareholders across an eight-year period were just 7.5 percent for conglomerates, compared with 11.8 percent for focused companies.

There have, of course, been many diversification strategies that have failed and many that have succeeded. Although it may be tempting to seek growth outside a company’s core business, this decision should not be taken lightly. The knowledge and skill required to manage business activities across multiple unrelated industries is hard to find, even among the most experienced and successful corporate individuals.