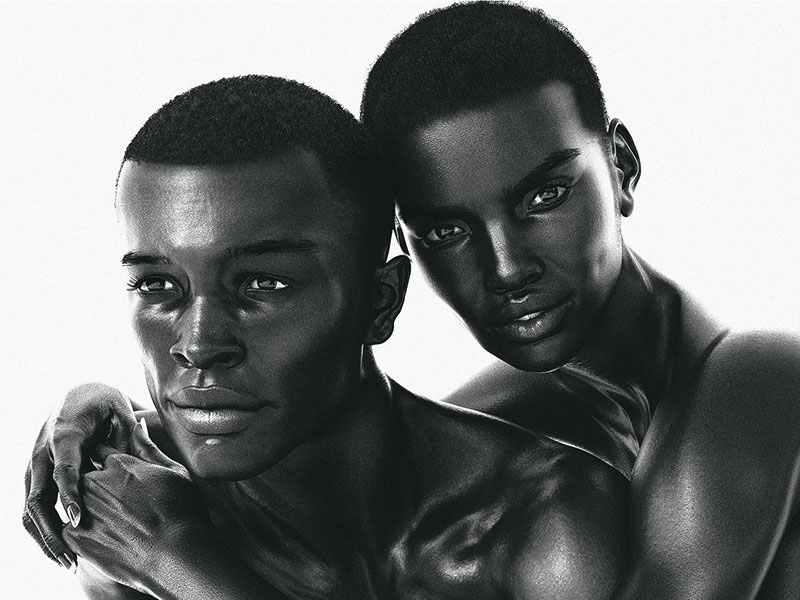

At first glance, there appeared to be nothing unusual about the three supermodels chosen to launch Balmain’s fashion campaign in September. The high cheekbones, flawless complexions and piercing stares could grace any glossy magazine or catwalk runway. They were not like other models, though: they had been entirely conjured up by computer software.

Margot, Shudu and Zhi – the names given to Balmain’s trio of CGI models – are part of the French fashion house’s “new virtual army”. Other designer brands are likely to enlist digital troops of their own – ones that are cheaper, just as eye-catching and easier to work with than real models. The use of virtual influencers in the fashion world is not without its critics, however: Michael Kors is not a fan, stating that he is “into real people with personalities and opinions”.

While some have championed these computer-generated beauties as modern examples of digital art, others have queried the potentially damaging effect they could have on beauty standards. One way or the other, the impact of these new virtual superstars is likely to be significant. Many of them have amassed hundreds of thousands of social media followers, and their numbers are growing all the time.

CGI-catching

When British photographer Cameron-James Wilson combined his passion for personalising Barbie dolls with his ability to create unique gaming avatars, he couldn’t possibly have imagined the impact it would have on both his life and the fashion world. His digital creation, Shudu, had not long been posted to his personal Facebook page before a friend shared it on Instagram. The comments came flooding in.

A CGI influencer is far less likely to damage a firm’s image by saying or doing something that is considered antithetical to its brand

Although Wilson was upfront about the fact Shudu was not a real model, the photorealistic nature of his creation meant that many people, including notable celebrities like Alicia Keys and Tyra Banks, thought that she was. This is testament to the quality of Wilson’s work, with each image taking approximately three full days to complete, in addition to weeks of planning.

“I created Shudu using a digital program called DAZ 3D that focuses on character creation,” Wilson told European CEO. “You basically work from a blank mannequin and build the character by slowly changing and customising every part of the body and skin texture/tone. It’s definitely time-consuming, but I find it a lot of fun, so I can’t say it’s labour-intensive.”

As Shudu’s social media following grew, Wilson began receiving offers from fashion and cosmetic brands hoping to collaborate. In addition to the Balmain campaign, the digital model has been used by Tiffany and the Bahrain-based womenswear firm Noon By Noor. But Shudu is not the only digital creation to capture the attention of major designers, nor is she the first. Brands are well aware of the reach and influence that these virtual influencers can bring to their marketing campaigns.

Miquela Sousa – or Lil Miquela, as she is better known – has 1.5 million followers on Instagram and, back in February, was used to promote Prada’s Fall 2018 collection. Like Shudu, she is computer generated; in contrast with Wilson’s creation, she prefers to blur the lines between reality and fiction.

As well as promoting products made by the likes of Chanel and Vans, Lil Miquela’s creators have given her political views, virtual friends and an ongoing narrative. Many real-life figures are happy to play along: she has been ‘pictured’ alongside Nile Rodgers and Diplo, while a number of media outlets have conducted interviews with her. Lil Miquela also has an online ‘frenemy’ in the form of a more right-wing virtual avatar called Bermuda, and has even started a music career.

Going out of fashion

While the success of digital influencers like Lil Miquela and Shudu may seem slightly bizarre – particularly to anyone who avoids social media fads – it does make sense from a business perspective. Brud, the Los-Angeles-based start-up responsible for creating Lil Miquela, has received millions of euros of venture capital investment.

Moreover, although some of these virtual models are sharing their lives on social media, the fact they are controlled by a creative agency gives companies choosing to partner with them added protection. For example, a CGI influencer is far less likely to damage a firm’s image by saying or doing something that is considered antithetical to its brand.

Further, digital models do not have to be flown around the world to take part in photoshoots, nor do they need to take a break every few hours. One UK firm, Irmaz, promises to provide brands with “imagined reality” models that are significantly cheaper than hiring a human alternative. What’s more, instead of having to search for somebody with a particular look, services like these allow businesses to create a model that’s perfect for their exact needs.

The emergence of digital modelling agencies has caused some real-life models to wonder if their careers are being threatened

The emergence of digital modelling agencies has caused some real-life models to wonder if their careers are being threatened by CGI rivals. During this year’s New York Fashion Week, model Gisele Alicea told Reuters that she did not think digital models would replace real people, but added: “The world changes all the time… I don’t want to lose my job.”

The likelihood of CGI models being used in place of the real thing, however, seems unlikely. First, the technical skill required to create a realistic digital model means that it’s probably still more economical for smaller brands to employ real-life models. Creating virtual versions of items of clothing may be more difficult still. For many brands, it will remain easier to simply pay for a professional model and photographer.

It is more likely that digital models will become another tool for fashion companies to use in their marketing efforts – working alongside real-life models, rather than replacing them. Digital models work well for advertisements and online content, but they cannot walk down a runway – not yet, anyway.

“Both real and 3D models have their strengths and weaknesses, and I believe they can both inhabit the fashion space,” Wilson said. “However, 3D models allow brands to make real investments into their narrative. This is a way for them to take time to develop the story behind their character, without the fear of them moving on to better contracts the following season.”

In addition, personality counts for a lot in the fashion world. The reason supermodels become globally known is not only for the clothes they wear: it is also related to who they are as people. This connection is difficult to fake, no matter how hard the creators of digital models try. Lil Miquela may have amassed a sizeable fanbase, but it still pales in comparison to the biggest stars in the modelling world: both Heidi Klum and Naomi Campbell have more than three times as many Instagram followers.

This is problematic. Instead of hiring a black model, the photographer created one. Is it that hard to pay black women? Also shows how much dark skin is still being exoticised by the media.

— Good Morning Africa (@MozaFrique) February 28, 2018

New faces

The fashion industry is often maligned for its lack of diversity. In fact, the Fashion Spot recently revealed that only 34.5 percent of the models used in fall 2018 fashion advertisements weren’t white. It’s perhaps unsurprising, then, that Wilson initially received a lot of praise for creating beautiful images of a dark-skinned woman. But not all of the comments he received were positive.

Criticism centred on whether it was right that a white photographer was profiting from a dark-skinned model without having to pay a black woman. One Twitter user claimed that Shudu’s popularity shows how dark skin continues to be “exoticised by the media”. Noël Duan, a writer who frequently specialises in issues relating to culture and lifestyle, accused Wilson of creating “an idealised (and fake) black woman… rather than devoting time and resources to cast and shoot real dark-skinned models and promote their beauty and careers”.

Similar complaints were levelled at Balmain, which also employed a virtual Asian model alongside Shudu. The slogan accompanying that particular campaign stressed that “anyone and everyone is always welcome to join the Balmain Army”, but the company’s words would no doubt have been taken more seriously if they had used real models instead of digital ones.

If using digital models makes it seem as though a company’s attitude towards diversity is little more than a marketing gimmick, then it should prepare for a backlash

“I don’t necessarily see digital models as improving representation in fashion, but just improving representation in general,” Wilson explained. “Art and media need to be more diverse across the board, not just models and photography. People want to see uplifting imagery, where they can see representations of themselves that are presented beautifully, and that’s what I can offer.”

If implemented sensitively, digital models could prove inspirational for underrepresented voices. Brands can create entirely new characters that emotionally connect with their customers. But if using digital models makes it seem as though a company’s attitude towards diversity is little more than a marketing gimmick, then it should prepare for a backlash. It will be a difficult balancing act to get right.

Keeping it real

The fashion industry already faces frequent criticism for perpetuating unrealistic beauty standards. Digital supermodels, with their flawless skin and eerily symmetrical faces, are unlikely to make things any better. “There is no world in which this is good for women’s health,” Renee Engeln, a professor at Northwestern University, recently told CNN. “To know that women are going to be comparing themselves to women who… are literally inhuman strikes me as some kind of joke that isn’t very funny.”

There is also a question of transparency that must be answered. When celebrities endorse a product or company, there are certain consumer standards that must be adhered to. How these apply to social media influencers that have been pieced together by a group of software developers at a creative agency is unclear. In an interview conducted by the Financial Times back in April, the only question Lil Miquela refused to answer related to sponsored online content.

Virtual fashion influencers that don’t exist outside of their social media channels are unlikely to be for everyone. It can all feel a bit soulless – which, considering the standards of authenticity set by the fashion industry, is actually quite impressive. The real-life stories of how the likes of Kate Moss and Gisele Bündchen were discovered are always likely to prove more engaging than those created on a computer screen. Still, these are early days for the technology.

“I think as fashion moves away from print advertising and more into digital and creating engaging events, this will only fuel new, exciting content,” Wilson said. “It’s hard for me to guess what may be in store because there are so many incredible tech companies working in this space that have incredible potential. Programs that allow you to speak any language, artificially intelligent 3D models, holograms on the runway – these are all in the here and now.”

As Wilson said, virtual supermodels are only likely to be the beginning of a digital overhaul of the fashion world. The likes of Shudu and Lil Miquela might not replace human models completely, but they may herald significant changes for the fashion industry and how customers interact with their favourite brands.