The need to appear as more than just a faceless corporation is what many marketing executives strive to achieve, usually through exhaustive trumpeting of their charitable and community initiatives. However, for some businesses, there is no better way of infusing a sense of taste and sophistication into the company culture than through investing heavily in a collection of art.

Corporate art collections have for many years been a way in which large companies engage with their clients and show that they are interested in more than just ever-increasing profits. This has been particularly true in some of the world’s larger banking institutions, as stunning pieces of art adorn the walls and foyers of many of Wall Street’s finest. Each of these collections tries to offer a glimpse into the unique and varied cultures of these firms.

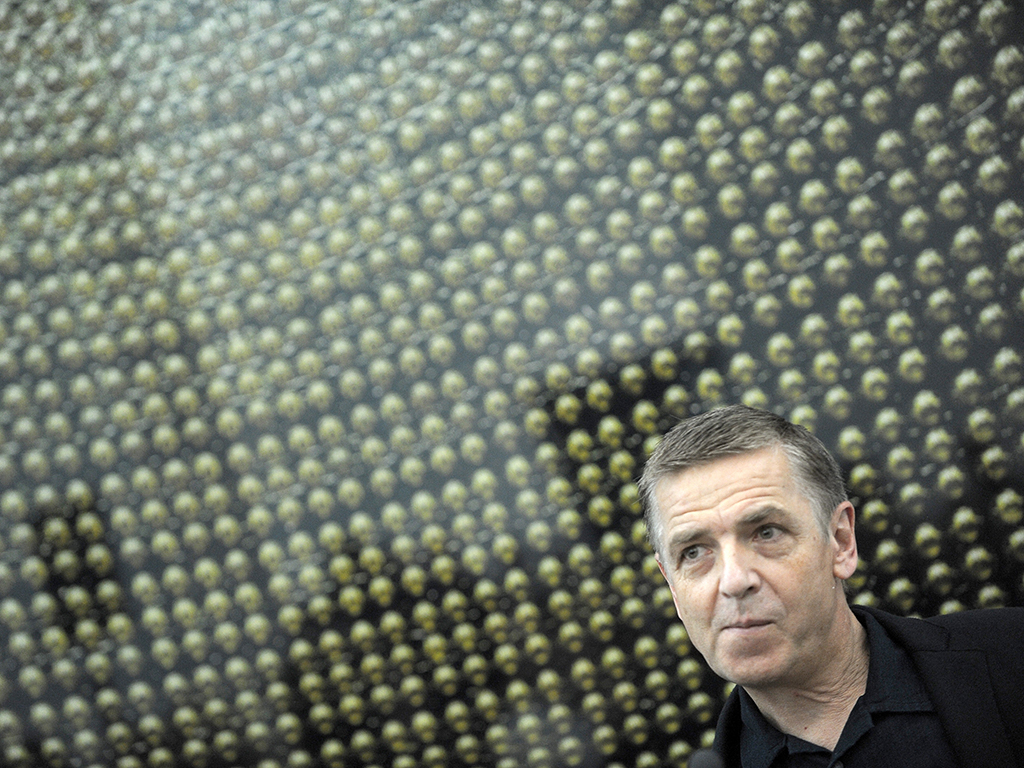

A recent book, A Celebration of Corporate Art Programmes Worldwide, highlights the breadth of these collections. Author Peter Harris told The Guardian in January about the variety found in the showrooms of many companies: “What I thought was amazing – and bear in mind I saw hundreds of art programmes – was that each one was different. They’ve all got a different rationale, different ideas, different ways, which makes it really interesting.”

A corporate art collection is beneficial to both the company and the artist, because it grabs the attention of the world

Harris says that a corporate art collection is beneficial to both the company and the artist, because it grabs the attention of the world. He adds that businesses do it in order to make the company seem like something other than a faceless corporation. “It’s for image. It is to tell the world and their employees things about them. If you go into any office before the staff arrives these days, they all look roughly the same: rows and rows of computers – and you think, what is this company all about? The answer is, it’s on the walls.”

Extravagance

Corporate art collections came under fire during the financial crisis as a sign of the extravagant excesses of banks. However, the prestige that these collections add to companies can sometimes prove invaluable in setting a company apart from its rivals. It can allow a firm to come across as far more sophisticated and in culturally in-touch than the average soulless, corporate moneymaking machine.

JPMorgan Chase is one of the most well known financial institutions in the world, with a rich and colourful history dating back well over a hundred years. It has also become well known for its vast collection of artworks, which gives the bank an impeccably well-heeled reputation. By contrast, smaller firms with collections worth less than what they paid could, at best, be described as foolish.

One firm that epitomised the excesses of the financial crisis was Lehmann Brothers. The first and largest casualty of the crisis, Lehmann was also known for its impressive collection of art. Two years after the collapse, the firm’s collection was auctioned off in a desperate effort to repay some of the creditors that had lost so much. Items included works by Lucien Freud, Gary Hume, Thomas Luny, Andreas Gursky and Damien Hirst. The European branch’s art secured £1.6m at auction, while in New York $12m was raised. Unfortunately, this was a drop in the ocean compared with what the firm ended up losing during the crisis. For it to invest in expensive pieces of art in the first place might offer a clue to the somewhat reckless way in which it handled its finances.

Origins

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. Many firms have become known for their patronage of the arts, without it damaging their profit margins. Lisa K Erf, director of the JPMorgan Chase Art Collection, told auction house Christies of the background to the bank’s impressive catalogue of art: “In 1959, David Rockefeller took the lead in corporate art collecting by establishing The Chase Manhattan Bank’s art programme. An advisory committee of leading American museum directors and curators guided a systematic approach to the purchase, display, educational uses and stewardship of the firm’s art collection. It became a model for companies worldwide by integrating artwork into the architecture of new buildings and incorporating an enlightened approach to acquisitions.”

Getting this collection together was an unexpected move for the bank, and one that helped to foster an inclusive and engaged culture for employees and clients. “During the 1960s, in the early days of the collection, it was a radical departure – the idea that art would no longer serve as mere decoration, but would promote a work environment that was visually and intellectually stimulating. Moreover, it would help create a progressive and inclusive culture for employees, clients and guests, an environment that engages with one’s capacity for critical thinking as well as nourishing the soul” said Erf.

Erf also mentioned that the collection represents a diverse range of works: “Today, the JPMorgan Chase Art Collection numbers 30,000 artworks situated within 450 corporate locations worldwide. Our collection continues to function as a ‘working asset’ to enhance our workplace for the enjoyment of employees, clients and guests, as well as to demonstrate key values of the firm: human creativity, innovation and diversity – first-class quality in everything we do.

Scotch collection

Another financial institution with a remarkably impressive collection of art is UK-based asset management firm Fleming Family and Partners (FF&P). An offshoot of the prestigious Robert Fleming and Co that was sold to Chase Manhattan – now part of JPMorgan Chase – in 2000 for $7bn, FF&P established the Fleming Collection in a gallery adjacent to its London offices. With a Scottish theme to the works, the collection includes more than 800 pieces by artists such as Samuel John Peploe, William McTaggart and Allan Ramsay.

Run by the Fleming-Wyfold Art Foundation, the collection represents the history of this prestigious financial institution. James Holloway, trustee of the foundation, told the BBC recently of the reasons for setting it up. “When the bank moved to bigger offices in 1968, they had so many bare walls and one of the directors at the time, David Donald, suggested buying art to cover them. To begin with, it was a case of buying purely nice things to fill up the spaces. It began to grow and people realised the collection was something of real interest. Almost by accident, the bank put together what was probably the finest private collection of Scottish art in the world.”

While many of these collections are for show, some companies might think that their investments may pay off financially in the future. However, because there are no earnings or dividends attributed to art, it isn’t really seen as a solid investment. Instead, people buying art to make money are doing so as speculation, and they will never really know how much they are going to get for the piece until it is sold.

These collections, however, represent something more than just money and profit. They show that companies want to engage with their clients and employees, and convey an image of themselves to the rest of the world. Whether this is part of their strategy to secure more business or a genuinely altruistic way of supporting the arts is a matter for personal judgement.