At the end of October, in Mario Draghi’s final council meeting, the outgoing European Central Bank (ECB) president struck an optimistic note. Having described his decision to cut rates into negative territory as “a very positive experience”, Draghi added that there had been a “general call to unity” in the governing council following the earlier backlash to his decision. On paper, his comments rang true: the council unanimously backed his decision to lower rates to -0.5 percent and restart the ECB’s bond-buying programme.

In practice, though, it would appear that this meeting contained more ceremony than substance. Just a month earlier, following another of Draghi’s council meetings, six hawkish former central bankers had sent an explosive memo to journalists attacking the ECB and its leader. For this rancour to have subsided in such a short period seems unlikely, to say the least – more probably, council members had taken flight from their outgoing president to begin circling their new chief, Christine Lagarde.

Public decrees of incertitude should serve as a warning to Lagarde that the headroom afforded to her predecessor might not be in quite the same abundance for her

The path laid out for the former International Monetary Fund (IMF) director is by no means clear. There are major structural issues, from debt levels to wealth distribution, that require addressing. At the same time, philosophical questions surround the core mission of the ECB – namely, whether it should retreat to its narrow mandate of price stability or continue expanding its policy toolkit. What’s more, all of these challenges will need to be handled with the help of an increasingly divided ECB council.

Feeling deflated

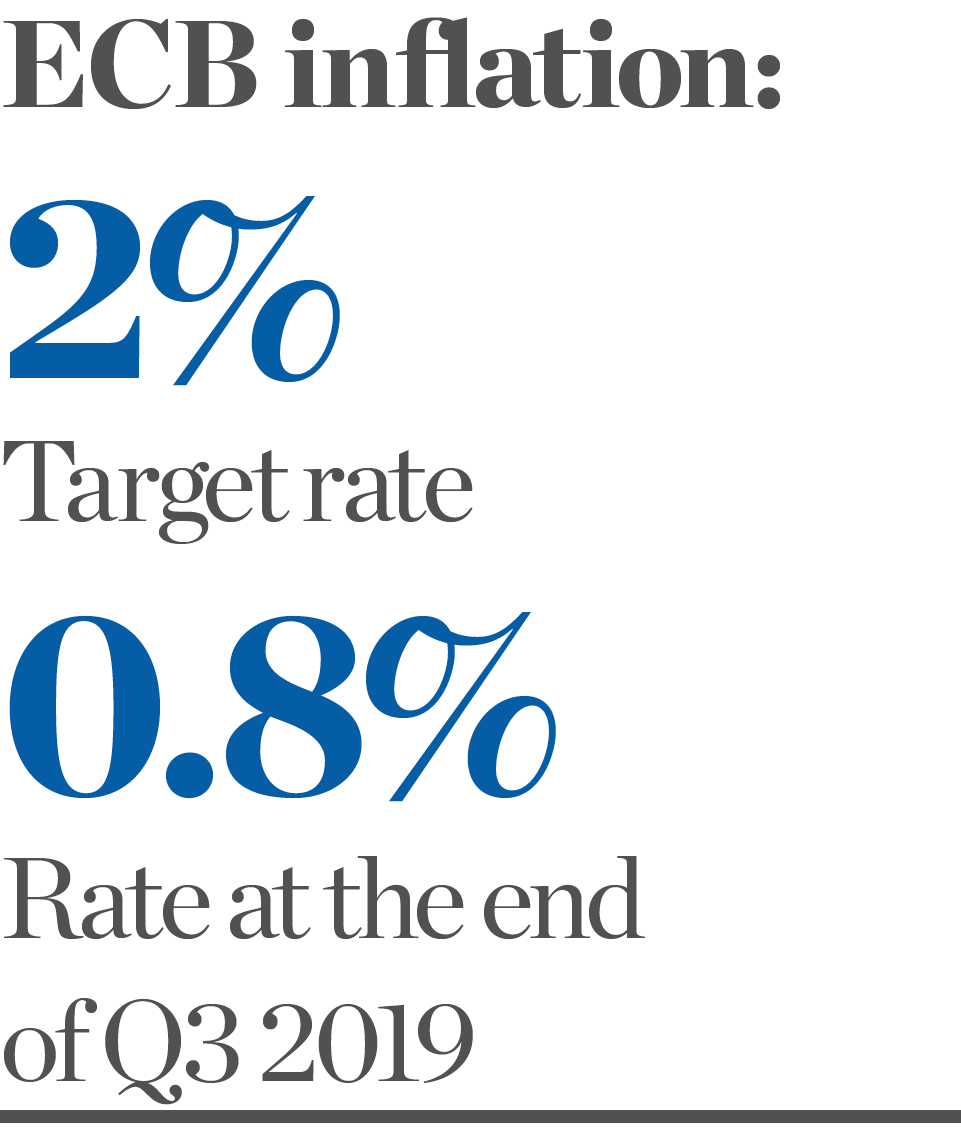

Draghi’s famed proclamation that he would “do whatever it takes” to save the euro in 2012 had far-reaching consequences. It’s true that he saved the euro, brought unemployment down (11 million people have been added to the European labour market since 2013) and stimulated euro wage growth, albeit slowly. But as a result of his efforts, the ECB now has a far larger balance sheet to contend with, and bond market yields are at record lows. Critically, the ECB is a long way off its inflation target of around two percent – in fact, at the end of September, inflation had fallen to a three-year low of 0.8 percent.

In their memo to journalists, ECB hawks argued that the central bank had previously “justified” quantitative easing (QE) as a way of nullifying the threat of deflation. They also stated that, given this danger no longer existed, there was no reason for its relaunch. The fear among hawks is that Lagarde will build upon Draghi’s expansionist approach by seeking a closer alignment of monetary and fiscal policy. This, they argue, would be in breach of the Maastricht Treaty, which bans monetary financing, and would therefore damage the ECB’s credibility.

“‘Whatever it takes’ can no longer be the ECB’s modus operandi under Christine Lagarde,” Neil MacKinnon, Global Macro Strategist at VTB Capital, told European CEO. “ECB hawks are concerned that a further drift into negative-rate territory would hasten Japanification, while a significant expansion in the ECB’s balance sheet is the road to debt monetisation.”

As journalist John Plender warned in an article written for the Financial Times, this debt monetisation risks creating a moral hazard: “If governments can fund budget deficits by selling their bonds to central banks rather than private investors, it neuters the discipline of the debt market.” This loss of discipline, Plender argued, leads to hyperinflation. It is also why hawks harbour suspicions that the ECB’s decision to restart QE is a means to “protect heavily indebted countries from a rise in interest rates”.

Watched like a hawk

There is a feeling around the ECB council table that the central bank is at a crossroads. With QE restarting and a new president at the helm, hawks like Deutsche Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann view this as their last opportunity to return to the remit of price stability. As Weidmann remarked to German weekly FAZ in August: “The current outlook is particularly uncertain.” This sentiment was echoed by the more moderate Banque de France Governor François Villeroy de Galhau, who called for the ECB’s first strategic review in 16 years.

These public decrees of incertitude should serve as a warning to Lagarde that the headroom – both economic and political – afforded to her predecessor might not be in quite the same abundance for her. But as Dr Matthias Weber, a professor at the School of Finance at the University of St Gallen, explained to European CEO, this group of hawks and hawkish moderates currently lacks the “critical mass” to seriously obstruct Lagarde’s work: “There seems to be only very few members of the governing council who view expansionary measures critically.” As such, there will likely be an increased emphasis on fiscal expansion under Lagarde’s leadership.

The former IMF director has already expressed her desire to deepen integration in the eurozone, believing this to be key to achieving financial stability in the bloc. By plugging the hole between national fiscal policy and global market integration, the ECB can act as an important safety net for the eurozone. This could be achieved – in part, at least – by taking the final steps towards setting up the European banking and capital market unions, the establishment of which would leave eurozone member states better placed to withstand future shocks.

But another way in which Lagarde could simultaneously improve the gloomy outlook for eurozone growth and quell the tensions inside her council is by encouraging greater spending from governments. This is no easy task, but signs of a sea change are emerging. Most notably, the typically cautious German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, suggested in September that the “political task that we have is, of course, not to overburden monetary policy”. It could be inferred from this comment that a more fiscally active approach might be adopted by the German Government, especially in light of the Bundesbank’s earlier warning that the country might slip into recession in Q3 2019.

Out of the comfort zone

Woes in the German economy spell trouble for the bloc. As the eurozone’s largest economy, Germany’s wellbeing is an important indicator of the health of the euro as a whole. In Q2 2019, eurozone growth fell to a meagre 0.2 percent – a climbdown from the already-modest 0.4 percent growth chalked up in Q1. With this in mind, it is worth questioning whether meeting the ECB’s inflation target should even be a high priority for Lagarde and her council.

“There are more pressing issues for policymakers to deal with than inflation,” David Scammell, a fixed-income macro strategist at Brown Shipley, told European CEO. “Political frustration with the pace of growth means that the pressure to do ‘whatever it takes’ will likely continue under the new leadership.”

Though Draghi failed to restore inflation to two percent, the monetary gymnastics he performed during the sovereign debt crisis deserve praise. After all, he salvaged a spiralling currency, kept the union intact and saw 19 member states achieve growth by 2017. It is testament to Draghi’s leadership that trust in the ECB has grown and support for the euro is at an all-time high. It will now be left to Lagarde – a lawyer by training – to call on her political experience to weather the incoming storm and build on the legacy of her predecessor.