As 2019 looms, the foremost event on the calendars of the powerful and wealthy is approaching. On the snow-capped slopes of the Alpine resort town of Davos, thousands of political leaders, business magnates and other trailblazers will gather in January for the World Economic Forum (WEF) Annual Meeting to discuss the most pressing issues on the global agenda.

This year’s meeting – entitled ‘Globalisation 4.0: Shaping a Global Architecture in the Age of the Fourth Industrial Revolution’ – will likely address the many uncertainties facing today’s economic landscape. In fact, it’s inevitable that leaders will seek to build on last year’s discussions, which sought to create a ‘shared future in a fractured world’ after a string of highly divisive world events plagued 2017.

Founded in 1971, the WEF is headquartered in Switzerland, a country synonymous with neutrality. In 2019, as global relations continue to struggle under the weight of clashing ideals, Davos is the perfect stage on which to continue hashing out a path towards unity.

Global architecture

“America first doesn’t mean America alone,” US President Donald Trump declared at Davos 2018. The statement provoked conversations about whether the world economy was being steered by isolationist policies and what damage could be done to globalisation. But Trump’s words were not followed by action: in fact, throughout 2018 he deepened fractures in the global economy by escalating a trade war with China over what he alleged were unfair trading practices by the communist nation.

The key issue faced by Beijing is that the America they used to know no longer exists

Jack Ma, the Chinese business tycoon who co-founded multinational technology conglomerate Alibaba, warned that a trade war could have the same implications as a physical war. “It’s so easy to launch a trade war, but it’s so difficult to stop the disaster of this war,” Ma said at Davos. “When you sanction the other country, you sanction small businesses, young people, and they will be killed, just like when you bomb somewhere. If trade stops, war starts.”

Yu Jie, China Research Fellow at Chatham House, agreed with Ma, telling European CEO that while a trade war could be unlimited and unspecified in its scope, “this potential economic crisis translates into an imminent political crisis and it affects every single aspect of the everyday life of the ordinary people [in China]”.

Trump did not heed Ma’s warning, however, and the US introduced a tariff on the import of solar panels and washing machines in January 2018. In March, the president boasted on Twitter that “trade wars are good, and easy to win”. He announced he would impose steep, unilateral tariffs on imports of steel and aluminium to the US in response to China dumping cheap steel on the market, which drove prices down for US producers. China, meanwhile, called the tariffs a “serious attack” on international trade.

The implications of Trump’s trade crusade rippled out to Europe as well. After a tit-for-tat skirmish, in which the EU threatened tariffs for the import of unmistakably American products, such as Kentucky bourbon, Levi’s jeans and Harley-Davidson motorcycles, a ceasefire was declared. It is not clear, however, whether peace will last. Even so, any dispute with China could disrupt the entire global supply chain. “It’s a trade war against the entire world, not just China,” Yu said.

When a country (USA) is losing many billions of dollars on trade with virtually every country it does business with, trade wars are good, and easy to win. Example, when we are down $100 billion with a certain country and they get cute, don’t trade anymore-we win big. It’s easy!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 2, 2018

In July, the US threatened tariffs on all $500bn (€439.6bn) of imported Chinese goods, and as the trade war engulfs more and more products, prices across numerous industries are expected to rise. The key issue faced by policymakers in Beijing is that the America they used to know no longer exists. While Chinese decision-makers are familiar with America’s intellectual elite – those who work on Wall Street and attended Harvard University – they now must learn to engage with, as Yu put it, an “unexpected and unpredictable president”.

This is a huge turning point for China’s international relations, and it could have major implications for its role in the global supply chain moving forward. Yu said: “This will potentially not just harm [the] Chinese economy for four years or eight years. This is for a generation.”

Logic error

The spotlight also turned on big technology firms at Davos 2018, with billionaire investor George Soros saying tech giants such as Facebook and Google had become “obstacles to innovation”. That criticism will likely carry over to this year’s discussions, after Google was fined a record $5bn (€4.4bn) by the EU in July for breaking competition rules. Margrethe Vestager, the EU’s competition commissioner, said that by forcing smartphone manufacturers to pre-install the Chrome web browser and search apps, Google had “denied rivals the chance to innovate and compete”, as well as “denied European consumers the benefits of effective competition”.

The fine was the latest move in the EU’s mission to crack down on the influence of US tech giants. Karin von Abrams, Principal Analyst at market research firm eMarketer, said: “[The EU has] been very consistent historically in trying to create an atmosphere, a legal structure and a system [that] enables it to bring companies and other entities to book if they feel that US firms – or firms headquartered elsewhere, for that matter – want to operate in Europe or take advantage of Europe to boost their own status or their income, but they don’t want to play by EU rules.”

Critical questions remain about the impact technology companies with staggering valuations could have on competition in the broader marketplace

Apple and Amazon are also likely to face increased scrutiny after becoming the first and second public companies ever to soar to valuations of $1trn (€879.2bn) this summer. “Valuations like this confirm that the tech industry really is increasing the engine of the world’s economy,” von Abrams said.

Although the technology sector is generating enormous fortunes and a substantial number of jobs, critical questions remain about the impact that companies with such staggering valuations could have on competition in the broader marketplace.

Von Abrams told European CEO: “We still live in a marketplace [that] we inherited substantially from an earlier era in terms of capitalism and commerce, but in a free market economy where things are changing so rapidly and these companies are becoming so valuable so quickly, they have really incalculable advantages over smaller tech firms.”

By investing – or failing to invest – in certain forms of technology, this handful of powerful firms has the ability to reshape the entire landscape of the tech sector. As technology creeps deeper into our lives, questions must be asked about the insidious influence it can have on aspects of society beyond the boundaries of its own industry.

One pertinent example is social media’s role in influencing recent elections. Earlier this year, Facebook was forced to issue a public apology after it emerged the firm had not safeguarded its users’ data, allowing information from almost 90 million accounts to be harvested by Cambridge Analytica. The now-defunct data firm allegedly used this information to show US voters personalised political advertisements based on their psychological profiles during the 2016 presidential election.

Facebook and Twitter both drew the ire of world leaders in 2018 for their alleged complacency regarding political interference on their platforms. Both sites have since removed fake accounts linked to Russia that tried to influence the US presidential election. Alongside an ongoing torrent of fake news, these revelations have certainly shaken global confidence in the democratic process.

“I think we’re really starting to understand just how radically disruptive some of the things that are happening [are]… on the political side,” von Abrams said.

“There are a number of really volatile situations that could have an enormous effect on all of us in a really, really short time, and I think a lot of us are just hoping that we’re not suddenly pitched into one of these chaotic situations and have to rethink the way the world works, because that would be quite challenging.” At a time when their valuations are soaring, one big question to focus on is whether these tech giants can be controlled, and what these controls might look like.

Another essential component of the technology revolution that will undoubtedly rumble through Davos again in 2019 is artificial intelligence (AI). In 2018, Ma called AI a “threat to human beings”, but said ideally it should be used to support us: “Technology should always do something that enables people, not disables people. The computer will always be smarter than you are; they never forget, they never get angry. But computers can never be as wise [as] man.”

Meanwhile, Google CEO Sundar Pichai said that while AI presents dangers, including the loss of jobs, the benefits cannot be ignored: “The risks are substantial, but the way you solve it is by looking ahead, thinking about it, thinking about AI safety from day one, and [being] transparent and open about how we pursue it.”

The WEF warned that AI could destabilise the financial system by introducing weaknesses and risks

In a recent report, the WEF itself warned that AI could destabilise the financial system by introducing weaknesses and risks. Although machine learning produces more convenient products for consumers, it also creates a world that is more vulnerable to cybersecurity risks, the report said.

As AI pushes further into the mainstream, inevitably fuelling greater concern and excitement, its prominence will only grow. “It’s a buzzword, of course,” von Abrams said. “But I think there will be further discussions simply because it does take time for people to understand more fully how they can apply it to their own business, and a lot of those applications are not yet reaching the real world.”

Brothers grim

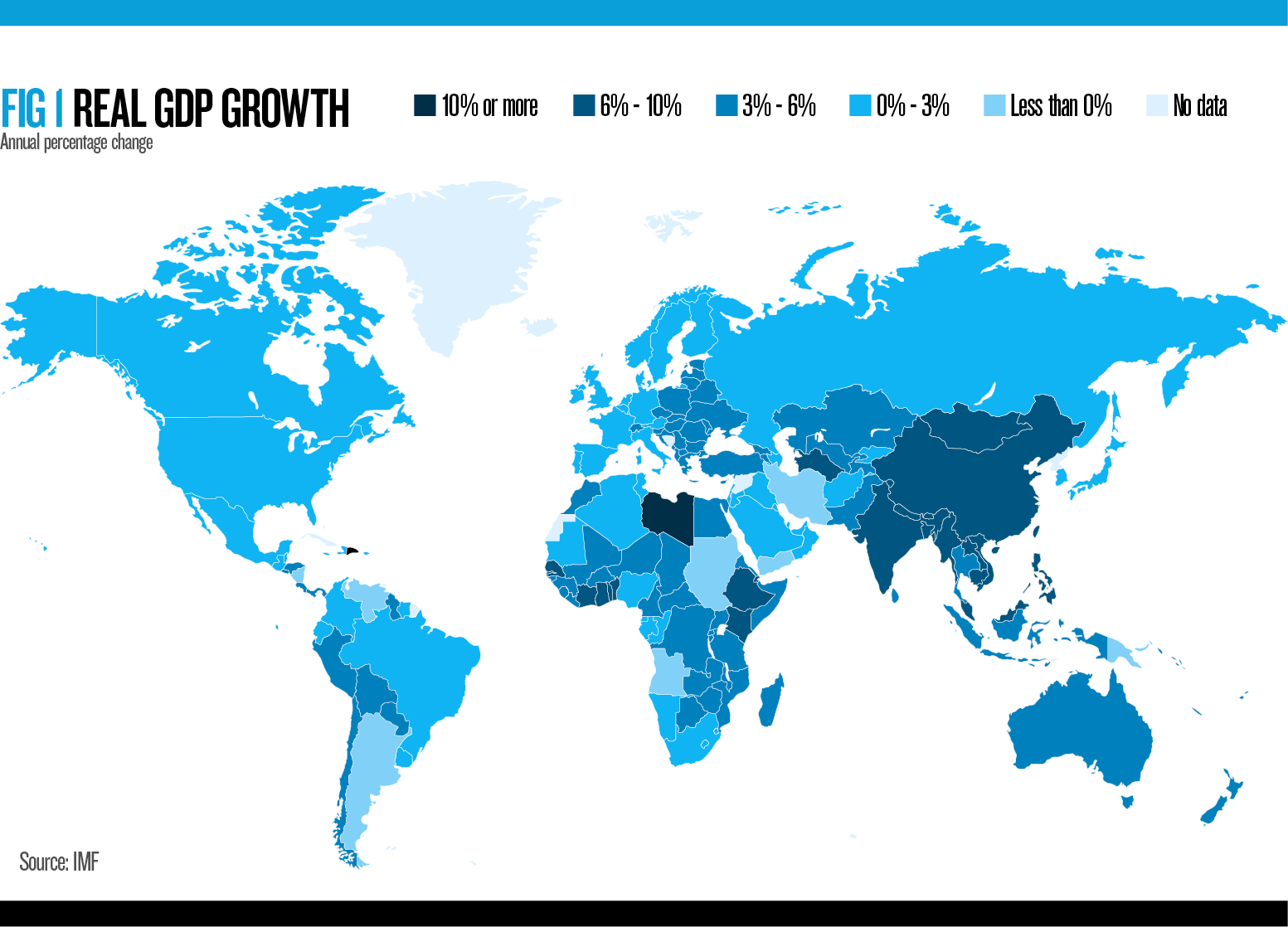

Despite heightened global tensions in 2018, the IMF has held fast to its expectation that the world economy will grow by 3.9 percent both this year and next (see Fig 1). The Trump administration’s protectionist tariffs are the “greatest near-term threat” that could knock this rise off-kilter, the IMF said.

In July, Maury Obstfeld, Economic Counsellor of the IMF, admitted that “the possibility for more buoyant growth than forecast has faded somewhat”. Meanwhile, the risks of the trade war have taken root; the IMF warned that if it escalates, 0.5 percent could be slashed off global growth by 2020.

In this time of uncertainty, world leaders are beginning to look back on how far the global economy has come in the past decade. This September marked the 10th anniversary of the collapse of US banking giant Lehman Brothers, which sparked a financial crisis that affected the lives of millions.

In a blog post, Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the IMF, said that while much had been done to clean up the financial system since 2008, the long shadow of the crisis “shows no sign of going away any time soon”. She added: “The fallout from the crisis – the heavy economic costs borne by ordinary people combined with the anger at seeing banks bailed out and bankers enjoying impunity, at a time when real wages continued to stagnate – is among the key factors in explaining the backlash against globalisation, particularly in advanced economies, and the erosion of trust in government and other institutions.”

According to Lagarde, the world now faces new fractures, including the potential rollback of post-crisis financial regulations, the fallout from excessive inequality, protectionism and rising global imbalances. How we respond to these new challenges will establish whether the lessons of the collapse of Lehman Brothers were learned. “The true legacy of the crisis cannot be adequately assessed after 10 years – because it is still being written,” Lagarde wrote.

Despite making up 47 percent of the labour force, women are still underrepresented at the highest ranks of business and at Davos

One key area that Lagarde stressed still needed more work was gender equality. She said that a crucial ingredient of reform is putting more women in financial leadership positions to reduce groupthink and increase prudence: “A higher share of women on the boards of banks and financial supervision agencies is associated with greater stability. As I have said many times, if it had been Lehman Sisters rather than Lehman Brothers, the world might well look a lot different today.”

But despite making up 47 percent of the labour force, women are still underrepresented at the highest ranks of business, including at Davos. The number of women attending Davos is low, but it continues to grow: in 2017, women made up about 20 percent of attendees, compared with 18 percent in 2016 and 17 percent the year before. The WEF’s 2018 annual meeting also featured an all-female panel of co-chairs. “Finally a real panel, not a ‘manel’,” quipped Lagarde at the time.

The #MeToo movement, which encourages people to speak out about sexual harassment, went viral in late 2017 and, at Davos 2018, dozens of panels addressed gender, diversity and inclusion, while two focused specifically on sexual harassment. Although the movement began in the film industry, #MeToo sent shockwaves through numerous sectors around the world in 2018.

All for one

Many other important issues will fight for recognition at Davos 2019. The debate around the effects of the climate crisis – and how the world should respond to them – has been a prominent feature of previous meetings. After a deluge of extreme weather events shook the globe in 2018 and a number of cities and countries began to crack down on single-use plastics, progress towards decarbonisation should continue to gain momentum in 2019.

Another area of progress in 2018 was the ongoing denuclearisation and peace talks between North and South Korea. The leaders of the two nations met for just the third time in 11 years in April, and Kim Jong-un was the first leader of North Korea to enter the South’s territory since the end of the Korean War in 1953.

Kim also met with Trump in June – the first time sitting leaders of the two nations had ever met. But while they signed a joint statement to work towards denuclearisation and rebuild bilateral relations, the agreement is shrouded in uncertainty as both sides have since derided one another, with Kim accusing the Trump administration of “gangster-like” behaviour.

Despite the attempts of many world leaders to repair fractures in global relations in 2018, there is still plenty of work to be done. Technology has made us increasingly connected, but it has also amplified the scale of many of the problems we face. Now, it is more important than ever for the WEF to stick to its mission to improve the state of the world by reinforcing unity across the globe.