Europe has a dirty money problem. For the past decade, the continent’s banking system has been awash with laundered funds – the product of illicit activities conducted by financial criminals. Legislative attempts to tackle the issue have proved fruitless, as there’s no overarching way of ensuring they are enshrined in law and correctly implemented.

What’s more, Europe’s financial institutions have turned their backs on investigative responsibilities due to the high price tag attached to such diligent processes. Any national attempts to address money laundering have not been wholly successful either, as the open, accessible nature of Europe’s financial framework means no door is ever really closed.

With greater instances of money laundering brought to the fore every year, the issue is taking its toll on countries across Europe. It’s clear a solution must be found – and fast.

Shining a light

There’s little mention of money laundering in Europe’s history books prior to the late 20th century, as the practice was predominantly confined to certain factions of the illegal drugs trade. However, this changed somewhat with the formation of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) at the 15th G7 summit in 1989.

Europe’s financial institutions have turned their backs on investigative responsibilities due to the high price tag attached to such diligent processes

“Money laundering… in the context of drugs was on the agenda at that summit, which triggered discussion [of the practice as a whole],” Katie Jackson, a partner at Deloitte’s financial crime team, told European CEO. “There was a recognition of the need to do something systemic across Europe, hence [the foundation of the] FATF.”

At the time, the FATF published its 40 Recommendations, which set the international standard for anti-money laundering (AML) measures. They were subsequently incorporated into EU law in 1990, with the introduction of the Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD), a piece of Europe-wide legislation that established a due diligence framework for financial institutions across the continent.

Money laundering was catapulted into the international spotlight in 2001 by the 9/11 attacks, which crystallised concerns that laundered funds could be used to finance terrorism-related activities. A global crackdown on money laundering ensued, with the FATF’s recommendations revised and expanded to include new guidelines on terrorism funding.

The AMLD was also updated to establish information-sharing guidelines for EU member states, while incorporating governments’ rights to “identify, trace, freeze, seize and confiscate any property and proceeds linked to criminal activities”.

Scandal upon scandal

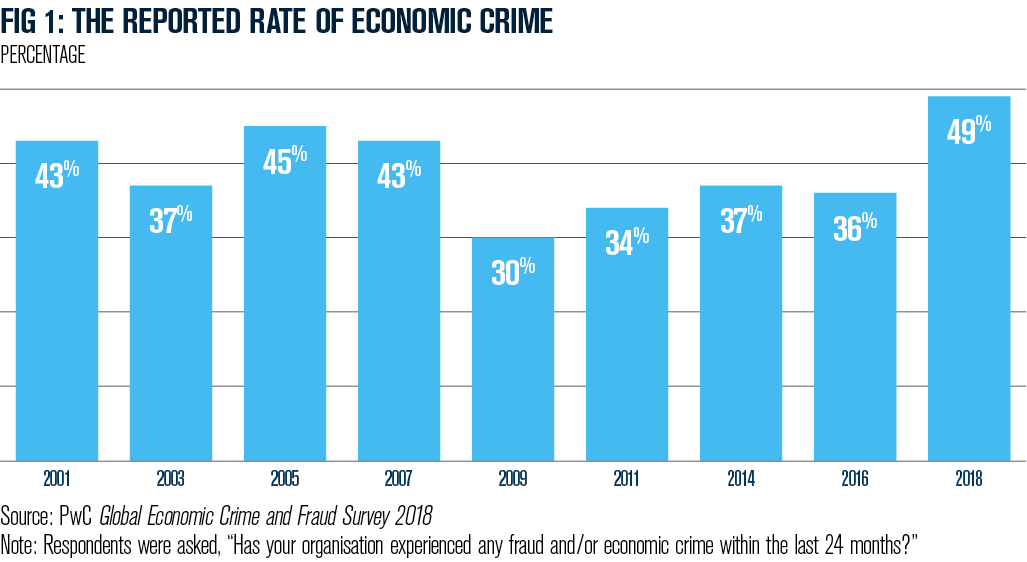

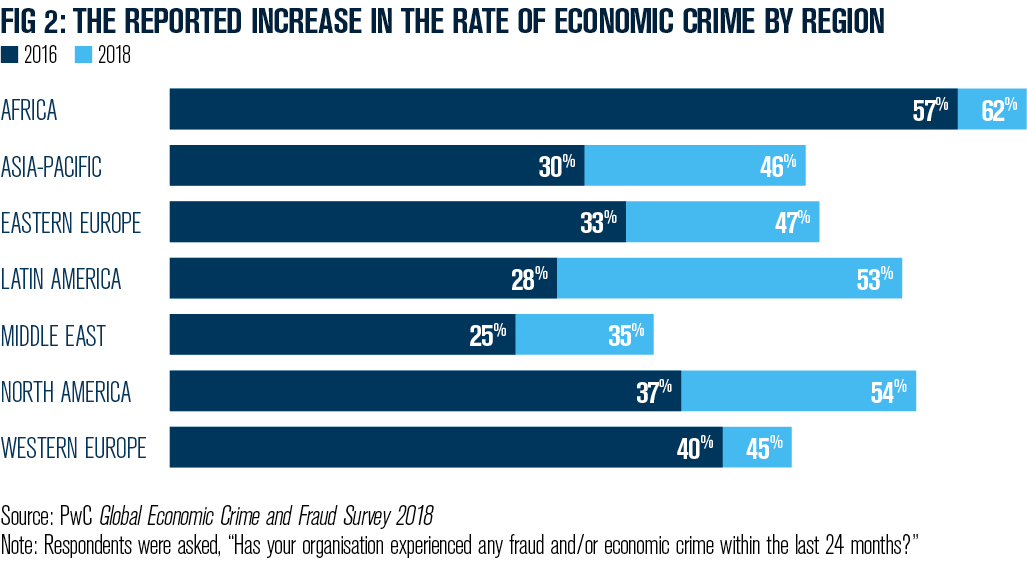

As far as the legislative authorities were concerned, the scene was set and the regulations were in place. But over the past few years, it has become increasingly clear that these measures have not been as successful as once hoped (see Fig 1 and Fig 2). Money laundering is not only alive and kicking, it has also caused some of Europe’s most significant financial scandals in continental history.

The trouble surfaced in 2016, when Dutch prosecutors began to investigate Netherlands-based lender ING after identifying a pattern of suspicious transactions from clients dating back to 2007. During the trial, which lasted almost two years, prosecutors said ING had violated AML laws “structurally… for years”, demonstrating a blatant disregard for repeated warnings received since 2008 about the robustness of ING’s security measures. Ralph Hamers, CEO of ING, said at the time: “Although our investments [in transaction monitoring] have been increasing since 2013, they have clearly not been to a sufficient level.”

In September 2018, ING was ordered to pay €675m in fines, plus an additional €100m to compensate for any profit it had made as a result of the crimes. Although the settlement was one of the largest ever handed out in the Netherlands, it was of little consequence to an institution of ING’s size, which posted a net result of €776m in Q3 2018 even after the fine was paid. Rather than being the deterrent it was intended to be, the fine simply knocked a zero or two off the bank’s sizeable yearly profit and left little lasting fiscal damage.

ING’s case sparked investigations into the institutional inaction that had rumbled on unchecked for the past decade. In July 2018, Estonia’s prosecutor general opened a criminal investigation against Danish national lender Danske Bank following allegations of a mass-scale money laundering operation. Over €200bn in suspicious transactions had reportedly flowed through a tiny Estonian branch of the bank between 2007 and 2015, predominantly through the accounts of British and Russian entities. The scandal was brought to light by British whistleblower Howard Wilkinson, who headed up the bank’s Baltics trading unit during that eight-year period.

The case has since swelled to massive proportions, engulfing Deutsche Bank, which has been named as a secondary lender. According to sources quoted by the Financial Times, the German bank helped to process some €181bn of corrupt funds for Danske across around one million transactions. In December 2018, the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project named Danske Bank as the 2019 Corrupt Actor of the Year, while Estonian authorities arrested at least 10 people in connection with the case. UK and US authorities have now launched their own investigations; the scandal is expected to persist for years to come.

Paying the price

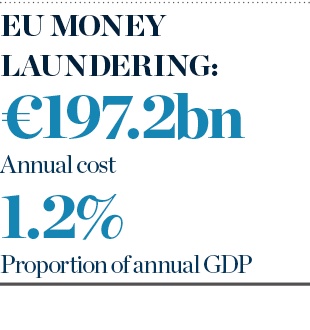

The question on everyone’s lips during the entire sordid affair was this: how did money laundering on this scale go undetected? Both Estonia and the Netherlands are part of Europe’s banking union, which is subject to no fewer than 19 different AML systems and regulations, including the AMLD. Yet, the ING and Danske Bank cases continued unpoliced for years. It’s not just a problem in these two countries, either: money laundering accounts for up to 1.2 percent of the EU’s annual GDP, or around $225.2bn (€197.2bn) in 2018, according to a 2017 report by Europol.

There are a number of reasons for this. First of all, it’s important to note the timing of Danske Bank and ING’s alleged transgressions: suspicious transactions were detected at both lenders as early as 2007, at the onset of the subprime mortgage crisis. While this doesn’t excuse the duo’s supposed lack of vigilance, it’s likely that both had greater concerns to contend with at that time, such as protecting themselves from collapse. Many financial institutions switched to ‘survival mode’ at that point, with operations trimmed down to the bare minimum. Fraudsters saw an opportunity and took it.

Second, the AMLD has frequently been criticised for its inefficacy, largely due to its lack of uniform implementation. As it is a directive, not a law, EU member states have a considerable amount of freedom in the way the AMLD is amalgamated into their respective constitutions. “Some countries still haven’t embedded the full requirements of the FATF [and the AMLD], because they just don’t have that driving political agenda,” Jackson said.

Moreover, the AMLD – like other AML legislation – is extremely costly to implement. The latest iteration of the AMLD – AMLD V, which is due to come into force in 2020 – is far more expensive than its predecessors, requiring banks to conduct Know Your Customer (KYC) checks on a more frequent basis. According to a 2017 whitepaper authored by Consult Hyperion, KYC processes currently cost the average bank $60m (€52.9m) annually, with some larger institutions spending up to $500m (€440.7m) every year on KYC and associated customer due diligence (CDD) compliance.

With these exponential costs set to skyrocket, it’s little wonder just 47 percent of banks in the UK told a 2017 Thomson Reuters survey that they had taken action to implement all new regulations. Over a third of the firms surveyed reported that scarce resources remained their greatest challenge when implementing KYC and CDD processes. “Ultimately, firms may have the best will in the world to prevent money laundering, but they are running a business at the same time and they have competing [financial] pressures,” Jackson said.

Many of the institutions surveyed by Thomson Reuters generated $10bn (€8.8bn) or more in revenue in 2017, meaning they should theoretically be financially robust enough to withstand increased AML costs. If institutions of this size are struggling, it doesn’t bode well for smaller banks in financially weaker EU countries.

For some financial institutions, there’s also a great deal of confusion surrounding AML regulations. Jackson said: “The risk-based approach is a core principle of AML directives and a number of firms, even today, still don’t really understand how to effectively apply that. So they don’t consider the holistic application of that principle, but they apply it in a very siloed way, which can prove to be quite costly, resulting in duplication of effort.”

Traversing borders

By far the greatest issue hindering AML measures in the EU, though, is the lack of cross-border information sharing and targeted action against money launderers. While each country within the bloc has its own financial intelligence unit (FIU) – whose main task is to identify suspicious transactions on behalf of prosecutors – these organisations do not share information with their international counterparts.

This is particularly problematic when attempting to tackle money laundering in the eurozone as a whole, as the countries with the flimsiest AML procedures tend to bear the brunt of the crime. This, in turn, has a knock-on effect on other nations within the bloc. As Jackson told European CEO: “You’re only as strong as your weakest link.”

Once a money launderer has broken into the European financial system via the weakest point of access, they’re able to run amok across the entire group. There’s certainly no shortage of crafty criminals, either. As former Europol chief Rob Wainwright told Politico in 2017: “Professional money launderers – and we have identified 400 at the top, top level in Europe – are running billions of illegal drug and other criminal profits through the banking system with a 99 percent success rate.”

The greatest issue hindering anti-money laundering measures in the eurozone is the lack of cross-border information sharing

According to a 2017 study by Europol, 65 percent of the suspicious transactions detected across Europe took place in the UK and the Netherlands. This came as a surprise for many, as both countries have advanced banking sectors and theoretically should have had highly robust AML procedures in place. Some, including the Dutch central bank, DNB, have placed the blame squarely with banks themselves. In a letter addressed to the Dutch finance minister in September 2018, the DNB wrote: “Too often we see that the [banking] sector insufficiently acts as a gatekeeper.”

Others have criticised the UK’s ineffectual AML procedures, many of which are carried out manually, with data taking months to be processed. “A number of the bigger [financial institutions] operating across multiple jurisdictions with diverse business units have archaic and fragmented systems, and their data is all over the place,” Jackson said. “They need to go back to basics, and undertake a complete transformation of what they do and how they do it based on what the [AML] requirements are.”

In light of recent political events, the UK’s insufficient framework is of particular concern to both British intelligence agencies and the EU itself. After Brexit, the UK will no longer be subject to the EU’s AMLD and will likely lose access to shared data on repeat money launderers within the EU, leaving a massive information-sharing gap for criminals to exploit.

However, Jackson is confident the overarching appetite to tackle money laundering will surpass any political impediments: “Politically and practically speaking, there will be certain elements that need to be worked through… but that doesn’t mean there’s any reason not to do it. We just need the right environment to support that kind of collaboration. As a European group of countries, we are in a much better position than ever before, but there is still much more to be done to drive that agenda forward.”

A better way

In order to tackle money laundering at the source, Europe needs a multilateral body with the power to not only share information, but also to prosecute perpetrators. It’s a popular solution to the issue, one that Jackson is very much in favour of: “[Financial] criminals are not bound by jurisdiction or borders, so we shouldn’t be either.”

Powerful European players, including former European Central Bank (ECB) Supervisory Board Chair Danièle Nouy, are also advocates, and have even begun preparatory work. Nouy, for example, confirmed the ECB was working on creating an AML office within its banking supervision jurisdiction to “act as a single point of entry with respect to the direct exchange of AML information between the ECB and AML authorities”.

The establishment of a body like this could help individual member states to cut costs with regards to AML procedures. “At the moment, the national bodies are spending a huge amount of money on processing suspicious activity reports, and the volume of information that they have to deal with is huge,” Jackson explained.

“If we could pool those activities into a central function that operated on behalf of Europe, everybody would only incur a slice of their current cost, rather than the burdensome cost that they have today. Let’s say the UK spends £100m [€115.2m] on the National Crime Agency – you could probably take £25m [€28.8m] from them, £25m from France, £25m from Germany [etc.] and you’d have a bigger pot overall, but you’d be operating on a much bigger scale and would be much more effective. It’s a win-win for everybody.”

As long as various regulators, financial institutions and governments play the blame game, financial criminals will continue to benefit from the vulnerabilities of the European banking framework

Such a body’s creation, however, relies on several key factors. First, in order for a multilateral agency with prosecutory powers to be set up, every EU member state would have to confer the AMLD regulations into law in a wholly unified way to ensure that criminals could be charged regardless of which country they were caught in. “We do have Europe-wide institutions and organisations that work very effectively across member states – there’s no reason why that couldn’t happen,” Jackson said.

A cohesive judgement as to whom is responsible for establishing this body and, by extension, tackling money laundering would also have to be reached. There’s no current consensus on this – some have postulated the burden should lay squarely with the banks, with fines increased to ruinous levels in a bid to force them to take AML responsibilities seriously.

However, this risks weakening the EU financial system overall and could drive significant market players out of business, or to move abroad. Others have said FIUs and regulators should do more to prevent money laundering at a national level but, as history has shown, this is not an effective solution. “Many of the actors that we’re trying to monitor… don’t work on a national basis, so we need a body that mirrors that and can work as seamlessly as they do,” Jackson told European CEO.

As long as various regulators, financial institutions and governments play the blame game, financial criminals will continue to benefit from the vulnerabilities of the European banking framework. A lax attitude in implementing AML policies – driven by confusion and high costs – has created an environment in which money launderers are able to clean funds rapidly and undetectably within the eurozone. We must now act to bring light into the darkest corners of the system, working to increase transparency and ensure that all funds passing through have legitimate sources. This will require cooperation on a governmental, logistical and financial level.

“I do think the political will is there,” Jackson said. “After all, [money laundering] is not just about drugs, but about loss of life and the impact on normal people, the economy and wider society day to day – human trafficking, prostitution, weapons [and] tax evasion.”

Financial crime has grown vastly in scope and scale, and any solution must certainly match – if not surpass – the role it has come to play in the European financial landscape. It’s time for money laundering to be put at the very top of the political, corporate and regulatory agenda – only then will the continent finally succeed in washing its hands of dirty money.