A decade ago, the eurozone was set to weather the most challenging fiscal storm it had seen since the establishment of the single currency. The sovereign debt crisis, which held the continent in an iron grip between 2008 and 2012, threatened the very bedrock of the European financial system. It brought the euro to the brink of collapse, sent Greek unemployment skyrocketing to 27 percent and ushered populist politicians into power in 10 of the eurozone’s 19 member states.

The causes of the crisis were myriad, complex and challenging to fully identify even with the gift of hindsight. The impact, however, is much clearer, for the debt crisis revealed some uncomfortable truths about power relations on the continent. The proposed solutions also created a number of significant economic and political rifts that continue to shape the way the single currency – and the EU more generally – functions today.

Beg, borrow or steal

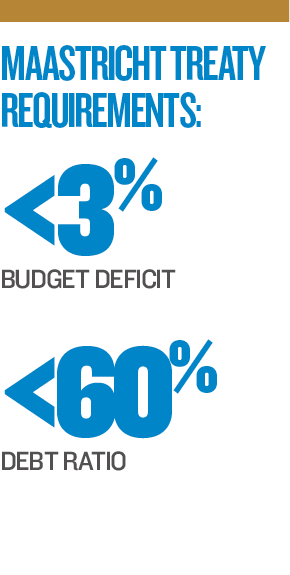

The story of the sovereign debt crisis began in 1992, with the signing of the Maastricht Treaty. Along with establishing a framework for political and social cooperation in Europe, the agreement set out provisions for a single currency, which was later introduced in 1999. Under the terms of the treaty, member states are required to meet certain conditions in order to adopt the euro as a currency – notably, maintaining a budget deficit below three percent of GDP and a debt ratio under 60 percent of GDP.

Some countries flouted these requirements in the early 2000s, however, as prosperous economic conditions and GDP growth across the EU diminished perceptions that increasing national deficits presented a looming threat. “If GDP is rising rapidly, then countries can have a large deficit without letting their debt-to-GDP ratio rise,” explained John Fender, a professor of macroeconomics at the University of Birmingham.

Further, the creation of a currency union meant that countries with previously weak currencies could suddenly access favourable credit conditions by adopting the euro. “You had countries such as Greece with fairly rackety credit histories suddenly being given impeccable credit histories, and they could borrow in a way that they couldn’t beforehand,” said Matthew Lynn, a financial journalist and author of Bust: Greece, the Euro and the Sovereign Debt Crisis. “Suddenly the speed limits were completely taken off.” This led some governments to borrow excessively without having the adequate support from national industries to fall back on.

In Greece, this excessive borrowing was coupled with a culture of corruption that led to a significant amount of creative licence being taken with the national budget. “Greece was keen to join the eurozone, but wasn’t too keen on fiscal discipline,” Fender told European CEO.

In fact, the Greek Government used a variety of deceptive accounting practices, off-balance-sheet transactions and complex derivatives structures drawn up by banks in the US to convince the EU that its national finances adhered to the rules set out by the Maastricht Treaty. In 2001, the EU was finally persuaded and Greece was granted permission to adopt the euro.

A Greek tragedy

Rather than change its behaviour once it had been accepted into the eurozone, Greece continued down the same path of overspending and deception. Fortunately, due to prosperous financial conditions in the early 2000s, the country was still able to balance its deficit with economic growth. “In Greece from about 2000 to 2007, the debt-to-GDP ratio hardly rose,” Fender explained. “But the government should be criticised for not reducing the debt when it had the opportunity to do so in those prosperous years.”

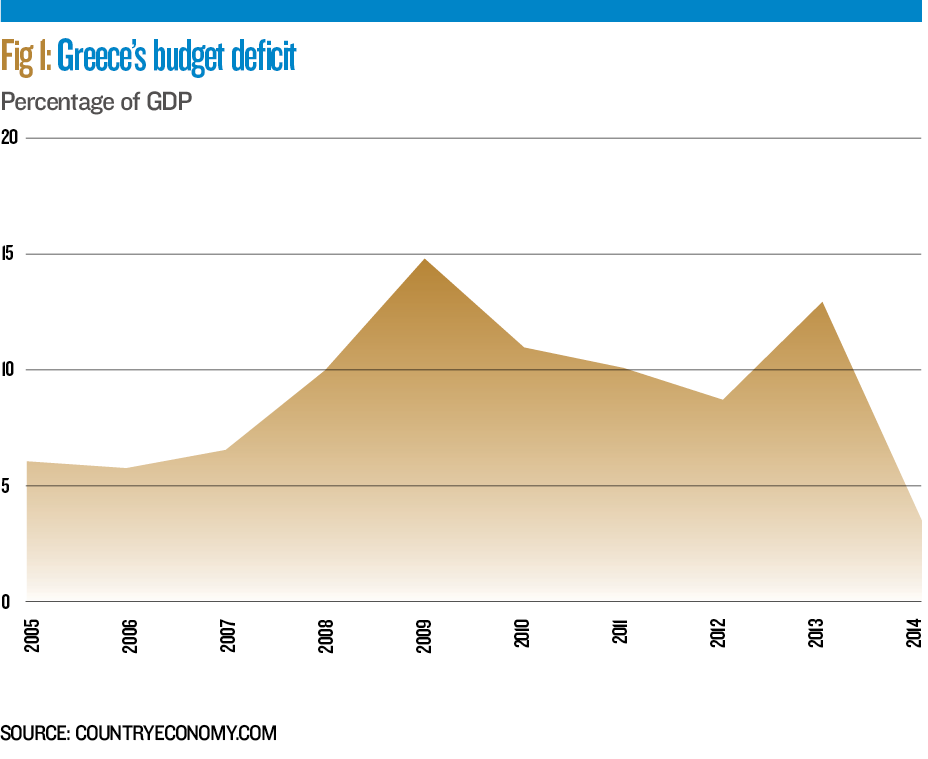

The size of Greece’s debt in and of itself was not a significant problem. Rather, the issue was that it left the country exposed if economic progress were to stall for some reason – which it did in 2008, when the financial crisis crippled markets around the world. By this point, Greece had amassed a significant structural deficit and, to make matters worse, the global recession had hit the country’s key industries of tourism and shipping particularly hard. In a bid to keep its economy functioning, the Greek Government spent even more heavily, increasing the nation’s deficit to around 15 percent of GDP in 2009 (see Fig 1) – well above the three percent limit outlined in the Maastricht Treaty.

If Greece went bankrupt, it would jeopardise the entire currency union

As the recession bit hard into Europe and banks looked to reduce their lending, Greece became the natural target, with word spreading of its financial mismanagement. In April 2010, the markets stopped lending to it, forcing the country to turn to the EU for help. Aid was initially refused, as bailouts are technically banned under the Maastricht Treaty, with some EU leaders, such as German Chancellor Angela Merkel, holding the view that Greece should be made to suffer the consequences of irresponsible borrowing.

Other leaders, however, understood that these problems extended beyond Greece to the eurozone: if Greece went bankrupt, it would jeopardise the entire currency union. With this in mind, a €110bn bailout was agreed, bringing with it a raft of tough austerity measures. But this was not enough to calm the markets and, with the help of the IMF, the EU was forced to build a €750bn firewall, known as the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), to protect the euro and account for any future bailouts. Ireland and Portugal would draw on the fund later that year, when financial markets also shut the door in their faces.

In 2011, Greece required a second bailout, one that – under pressure from EU leaders – the continent’s banks duly offered, writing off 50 percent of the country’s loan debt. This soured relations between the markets and European governments, dashing any hopes of an immediate end to the crisis in the process. Credit agencies such as Standard & Poor’s and Fitch continued to downgrade European countries’ credit ratings, while the rest of the world grew increasingly fearful that the single currency would collapse.

The turning point came in July 2012, when Mario Draghi, President of the European Central Bank (ECB), delivered a speech to global business leaders, promising that the central bank would “do whatever it takes to protect the euro”. The ECB subsequently slashed interest rates and introduced quantitative easing. These measures paved the way to recovery by calming markets, providing liquidity to indebted countries and stimulating economic growth.

The blame game

In total, five eurozone countries received bailouts from the EFSF between 2009 and 2014, while Greece came within spitting distance of being ejected from the euro – saved only by the grace of French President François Hollande, Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi and a 4am emergency meeting in Brussels. The real crux of the crisis was not money, though, but control. What played out over the course of those five years exposed a number of uncomfortable truths about power relations in the eurozone – between individual nations, financial institutions and the EU itself.

First, if the 2008 financial crisis demonstrated the extent to which entire national economies were beholden to banks and their lending decisions, then the debt crisis really hammered it home. Just 18 months before it all came crashing down for Greece, countries across the eurozone had been forced to bail out their own over-indebted financial institutions as a result of their irresponsible lending choices.

In 2008, the French Government spent €10.5bn of its own budget rescuing the country’s six largest banks, after Hollande’s predecessor, Nicolas Sarkozy, pledged that no saver would lose “a single euro” as a result of the recession. Merkel, meanwhile, announced a €500bn bailout fund for the banking sector, the biggest state intervention in Germany since the Second World War.

These rescue packages effectively shifted the burden of private debt onto public shoulders, making taxpayers responsible for banks’ irresponsible lending system. “[At the time,] the large increase in private debt and the explosion of lending suddenly became a concern for policymakers,” Fender said. “But there really was no alternative to bailing out the banking system if we didn’t want to let it collapse.”

When the tables turned in 2009, however, the banks did not leap to governments’ aid. Rather, they closed financial markets and refused to lend to heavily indebted economies – Greece being a prime example. Given the interdependency of the European financial system – where if one country defaulted on its debts, financial contagion would soon follow – this decision significantly worsened the crisis.

By refusing to lend, banks knew that the debt burden would simply be cast onto the shoulders of another eurozone country, significantly increasing the likelihood of an overall collapse of the currency union. While some may say this was an economically sound business decision, the fact remains that it is one that knowingly deepened the crisis.

Furthermore, a number of US banks had actually facilitated Greece’s fall into an expanding pit of debt, providing it with complicated derivatives products that the country used to conceal the true size of its deficit. “Banks eagerly exploited what was, for them, a highly lucrative symbiosis with free-spending governments,” wrote Louise Story, Landon Thomas Jr and Nelson D Schwartz in The New York Times.

Goldman Sachs, for example, was accused of helping the Greek Government borrow billions of euros in a concealed currency trade in 2001, despite knowing the country was spending well beyond its means. The US investment bank reportedly earned a healthy $300m (€266.7m) in fees for that deal, according to sources quoted in The New York Times article. Goldman Sachs declined to comment on the issue.

While it wouldn’t be justifiable to say the banks should have picked up the slack for the Greek Government’s financial mismanagement, it is hard not to condemn them for pulling out the second the going got tough. The crisis impressed upon European leaders just how reliant their countries had become on the banking sector, which had been more than willing to accept the same governments’ help in similar circumstances a year earlier. This seemed particularly unjust when certain banks had been instrumental in causing the crisis in the first place.

Protecting the union

“The banks did play a certain role in the build-up [to] the debt crisis that they can be criticised for,” Lynn told European CEO. “But the real issue was the policy response.” By far the greatest revelation of the crisis was just how inequitable the relationship between smaller EU economies and the bloc’s more powerful players was, and the level of control the latter expected to exercise when things got difficult.

When Greece was forced to ask for financial aid in 2010, for example, it drew the ire of EU leaders, who wanted to punish the country for its fiscal irresponsibility. In exchange for a bailout, the EU imposed a raft of highly restrictive austerity measures, including a pay freeze on all public sector workers, an increase in value-added tax and changes to pension schemes that forced workers to retire later.

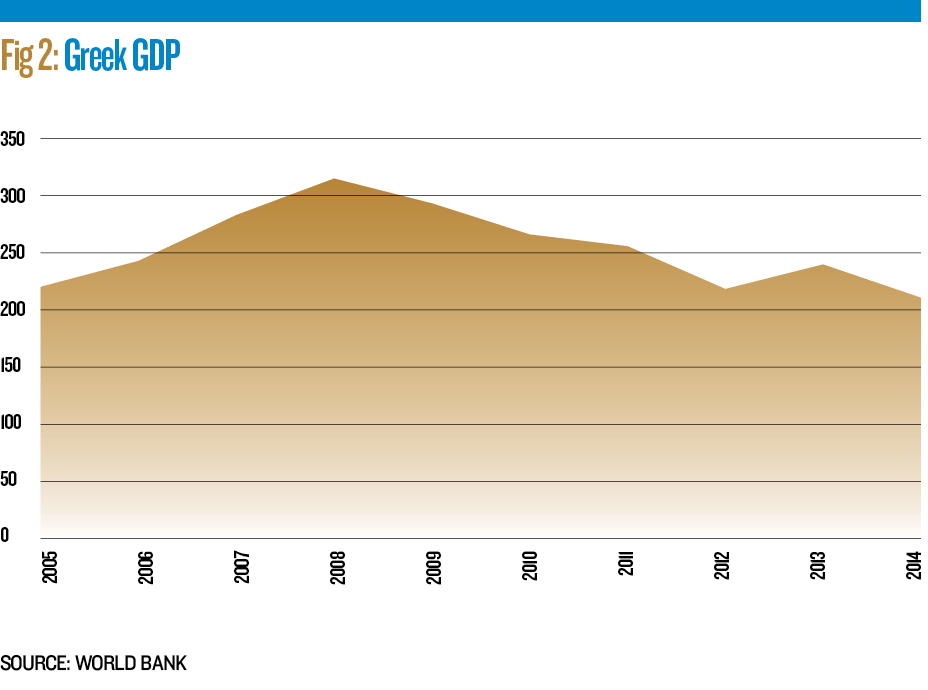

“The Draconian response of the European authorities created this completely unnecessary massive recession and the biggest economic contraction ever recorded since statistics began,” Lynn said. Greece’s GDP fell by more than 25 percent between 2009 and 2014 (see Fig 2), unemployment rose to 27 percent in some areas, and ATM withdrawals were limited to €60 per day.

The imposition of these measures drew hostility from both the Greek Government and the Greek people. “Having to beg for [a bailout] is not really something one wants to do, and one puts oneself at the mercy of other countries – it generates a lot of discontent,” Fender said. In fact, it led to the election of a Eurosceptic government; a phenomenon that would extend beyond Greece to Italy, Poland and the Netherlands. “[The austerity measures] did fuel the rise in populism and in Euroscepticism across the continent,” Lynn said.

The message the EU tried to send was clear: once you’re in, you’re in

The reason Greece was treated so harshly was because it had endangered the EU’s most ambitious project: the single currency. For many within the bloc, this was not just an economic affront, but also one that threatened the very basis upon which the organisation had been built. “The euro was launched as a way of cementing the EU as a single political and economic entity,” Lynn said. “The EU took a decision to defend it come what may.”

Some leaders were willing to let Greece simply crash out of the currency and return to the drachma. “They said, ‘Oh, they fiddled all the numbers, they weren’t ready to join the euro, we shouldn’t have let them in’,” Lynn said. “So it would have been an option to reverse that policy.”

But some were adamant Greece should be saved, not least Sarkozy, who told Merkel and other EU leaders: “It’s not about saving Greece, it’s about saving Europe… More precisely, about saving the euro.” Sarkozy’s comment highlighted the centrality of the single currency to European identity. It was viewed as far more than a means of payment – it was seen as a tool for continental integration and a symbol of shared values.

There was another element to the argument, too. “I think European leaders wanted to create a single currency that was so genuinely single that no one ever thought about leaving,” Lynn said. “As soon as you create a door – an exit – then, in a funny way, it stops being a currency… It becomes something else.”

By ensuring that Greece remained within the euro, EU leaders saw themselves as upholding the values of openness, democracy, forgiveness and unity that the entire organisation was founded upon. Had they allowed it to leave, that may have paved the way for other countries to opt out, which would have been seen as a rejection of all those values and, in some ways, a return to a period of recent history characterised by division and violence. The message they tried to send was clear: once you’re in, you’re in.

Paying for the privilege

On closer inspection, then, the sovereign debt crisis is not a story of economic weakness: it is a tale of pride and punishment, power and subordination, and shame and control. It challenged the core values of the EU and revealed the weaknesses of a project that relied on political and economic alignment. As with any other pioneering venture that depends on human cooperation, it is fragile by its very nature.

The debt crisis also showed that the single currency has become a test for entry into a political club, membership of which means adhering to a set of rules or being punished for insubordination. The majority of eurozone countries have viewed this as a reasonable price to pay to be part of something greater and have relinquished a little of their sovereignty in exchange for more favourable credit conditions, improved economic growth, a more prosperous business environment and a stronger presence on the global stage.

The euro remains an incredibly ambitious project, but one that still has the potential to bear fruit. In order to do so, however, it will require cooperation from all parties – both public and private – lest some members be left to foot the bill for others’ irresponsibility. After all, rules exist for a reason.